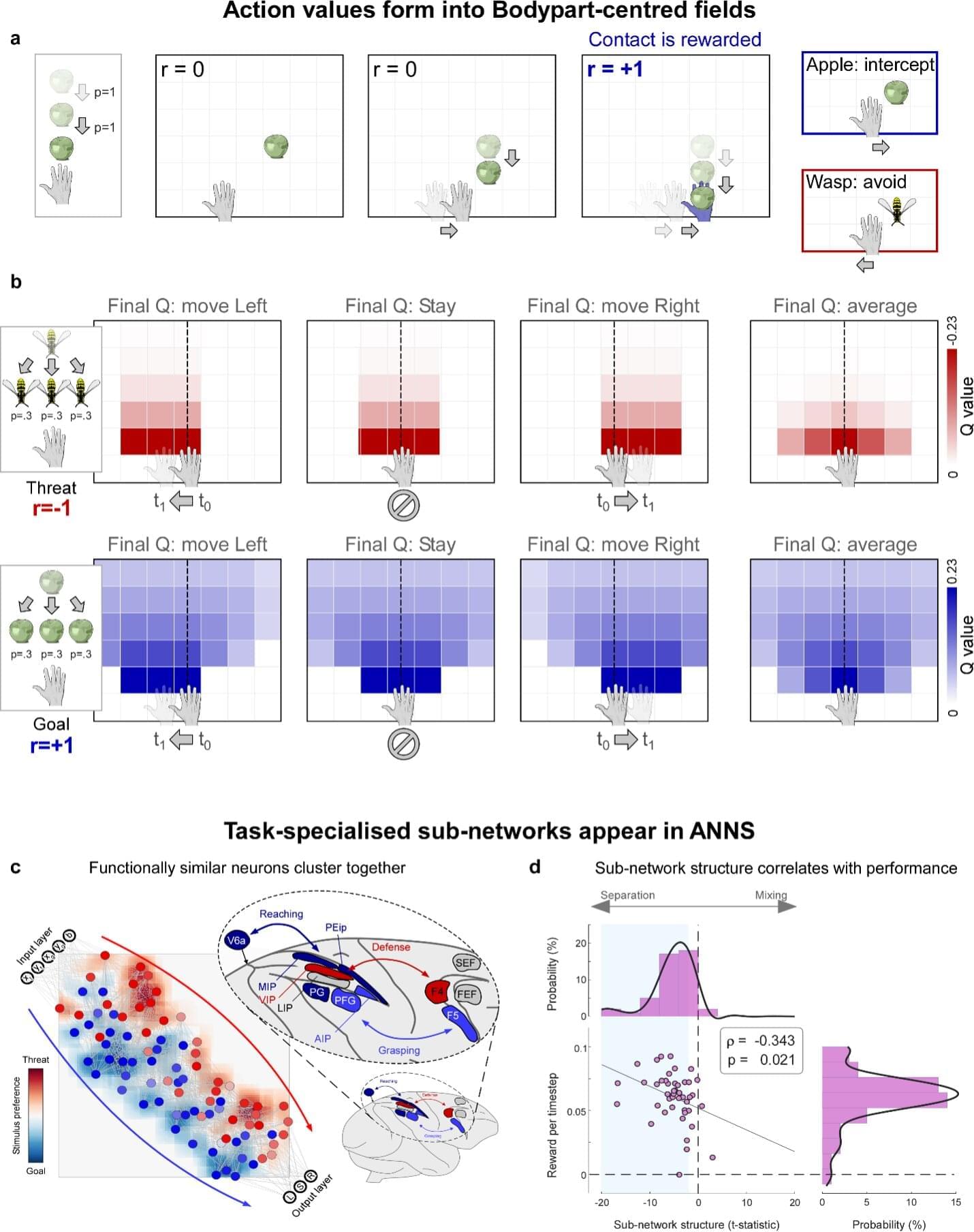

The brains of humans and other primates are known to execute various sophisticated functions, one of which is the representation of the space immediately surrounding the body. This area, also sometimes referred to as “peripersonal space,” is where most interactions between people and their surrounding environment typically take place.

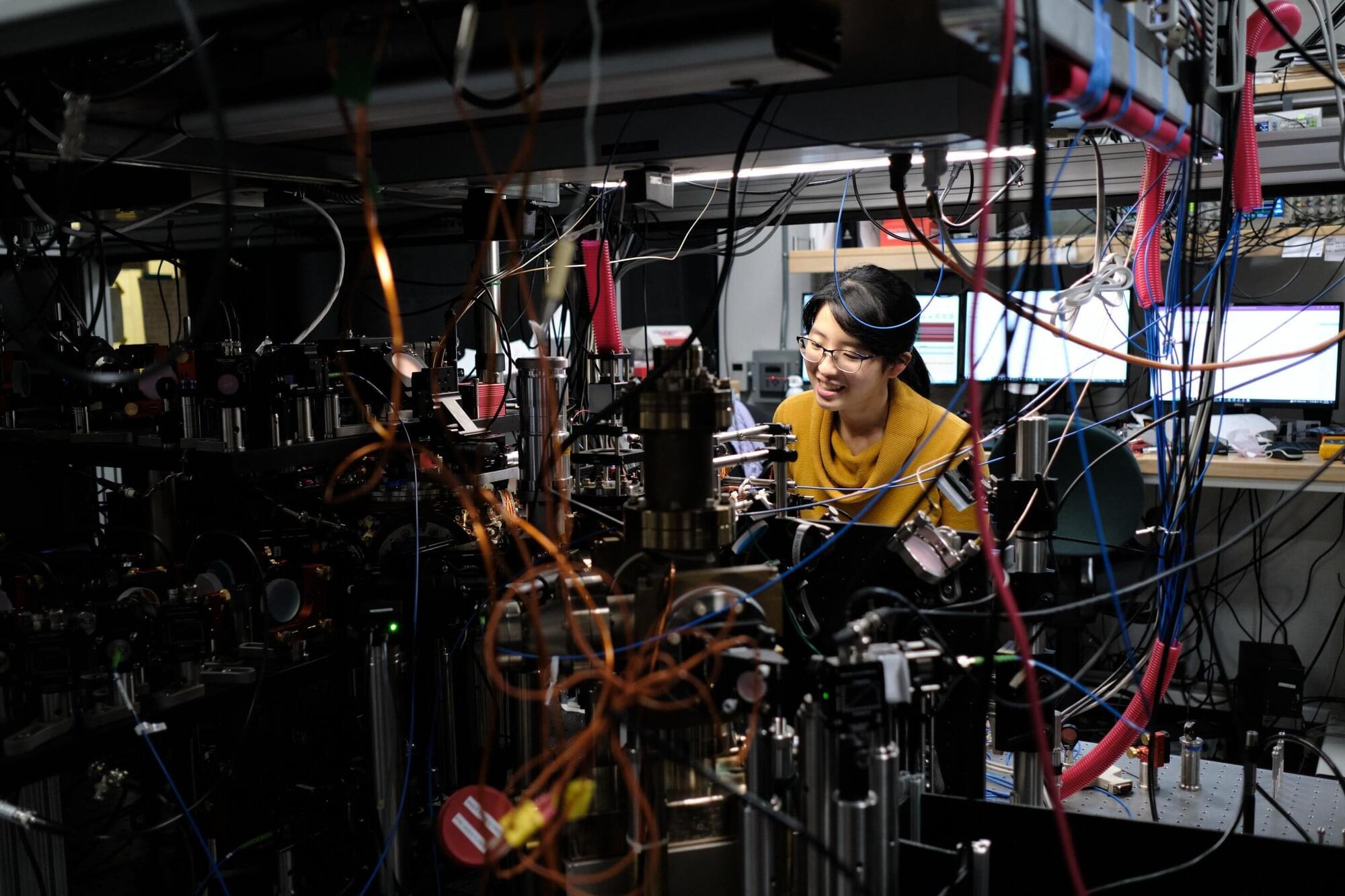

Researchers at Chinese Academy of Sciences, Italian Institute of Technology (IIT) and other institutes recently investigated the neural processes through which the brain represents the area around the body, using brain-inspired computational models. Their findings, published in Nature Neuroscience, suggest that receptive fields surrounding different parts of the body contribute to building a modular model of the space immediately surrounding a person or artificial intelligence (AI) agent.

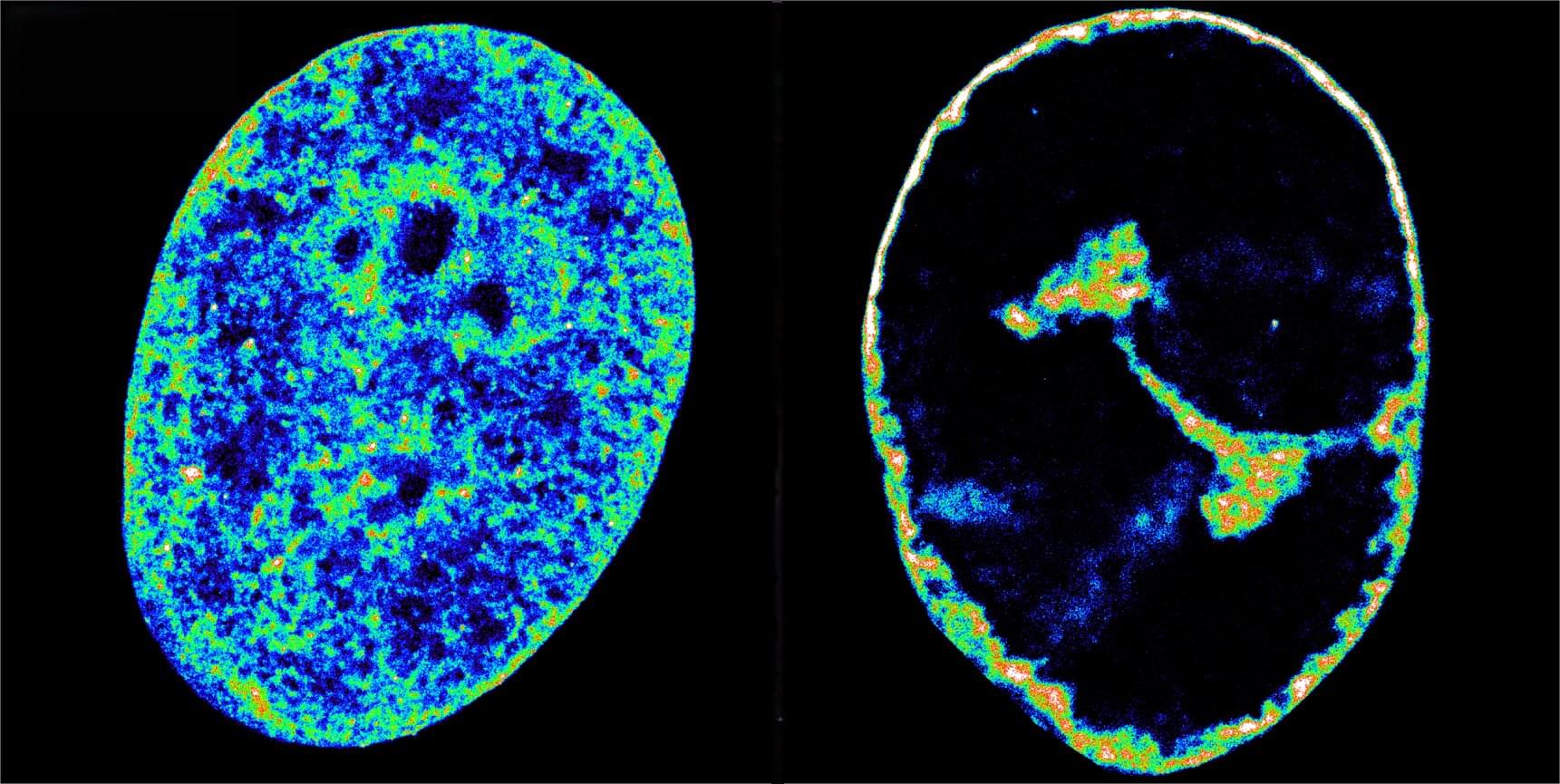

“Our journey into this field began truly serendipitously, during unfunded experiments done purely out of curiosity,” Giandomenico Iannetti, senior author of the paper, told Medical Xpress. “We discovered that the hand-blink reflex, which is evoked by electrically shocking the hand, was strongly modulated by the position of the hand with respect to the eye.