“Our study points to sex-and environment-specific effects of a common genetic variant. In the mice, we observed that Ghrd3 leads to a ‘female-like’ expression pattern of dozens of genes in male livers under calorie restriction, which potentially leads to the observed size reduction,” Saitou says.

“Females, already smaller in size, may suffer from negative evolutionary consequences if they lose body weight. Thus, it is a reasonable and also very interesting hypothesis that a genetic variant that may affect response to nutritional stress has evolved in a sex-specific manner,” Mu says.

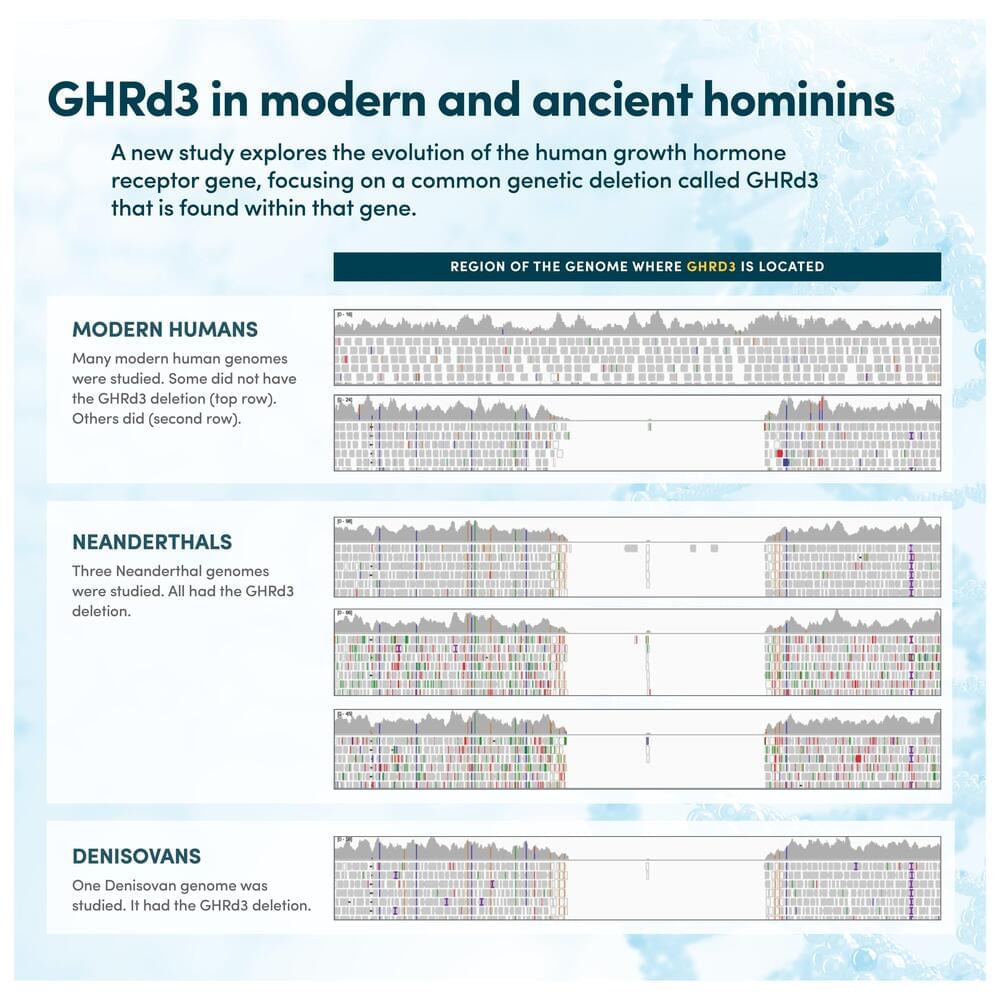

A new study delves into the evolution and function of the human growth hormone receptor gene, and asks what forces in humanity’s past may have driven changes to this vital piece of DNA.

The research shows, through multiple avenues, that a shortened version of the gene—a variant known as GHRd3—may help people survive in situations where resources are scarce or unpredictable.

Findings will be published on Sept. 24 in Science Advances.