In this video I’ll show you how increasing your Internet Connection Speed by 100 times is possible and where that has been accomplished.

A world record fastest data transmission rate and fastest Internet Ping has been achieved by a team of University College London engineers who reached an internet speed a fifth faster than the previous record.

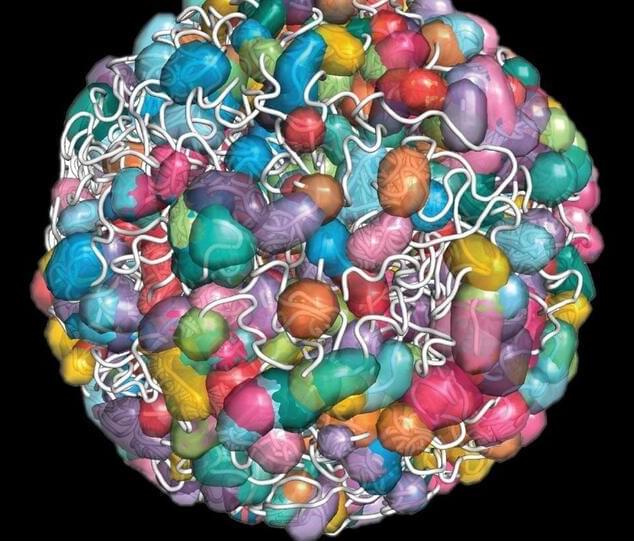

It’s faster tgab 100tb a second and can download or upload pretty much anything instantly.

The best part about that is that ISP’s like Google Fiber, Comcast or Verizon will have an easy time improving their Internet Connections due to the new technology using similar kind of cables to achieve this super fast internet speed.

–

If you enjoyed this video, please consider rating this video and subscribing to our channel for more frequent uploads. Thank you! smile

–

TIMESTAMPS:

00:00 A Record Breaking Internet Speed.

02:02 How Internet Speed is measured.

02:55 How this technology works.

05:09 Another revolutionary Internet Provider.

06:24 Other important aspects of Internet Speed.

07:18 Last Words.

–

#internet #speed #ai