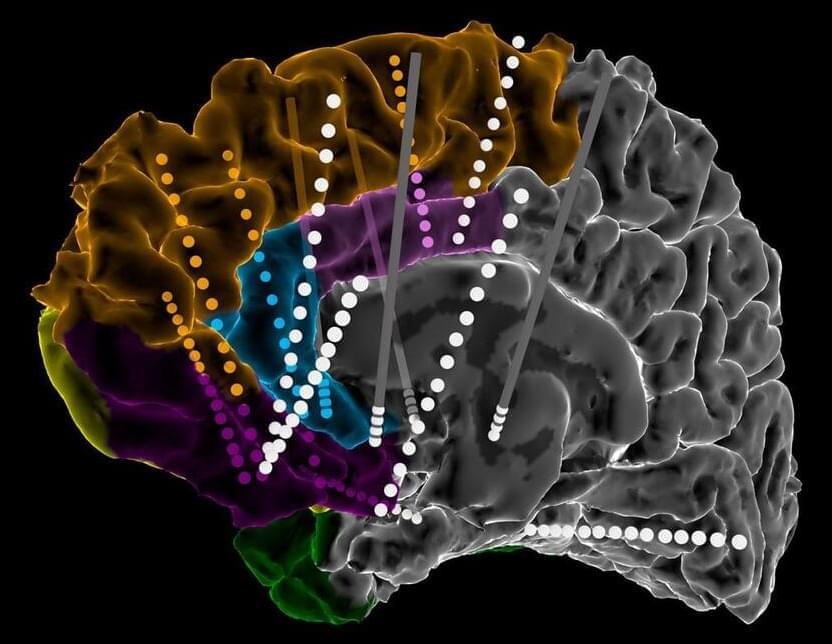

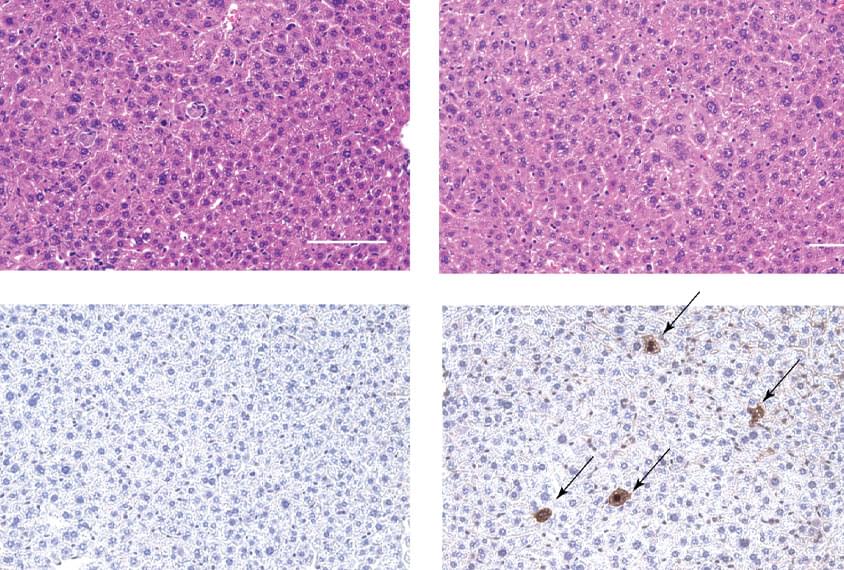

Over the past several decades, researchers have moved from using electric currents to manipulating light waves in the near-infrared range for telecommunications applications such as high-speed 5G networks, biosensors on a chip, and driverless cars. This research area, known as integrated photonics, is fast evolving and investigators are now exploring the shorter—visible—wavelength range to develop a broad variety of emerging applications. These include chip-scale LIDAR (light detection and ranging), AR/VR/MR (augmented/virtual/mixed reality) goggles, holographic displays, quantum information processing chips, and implantable optogenetic probes in the brain.

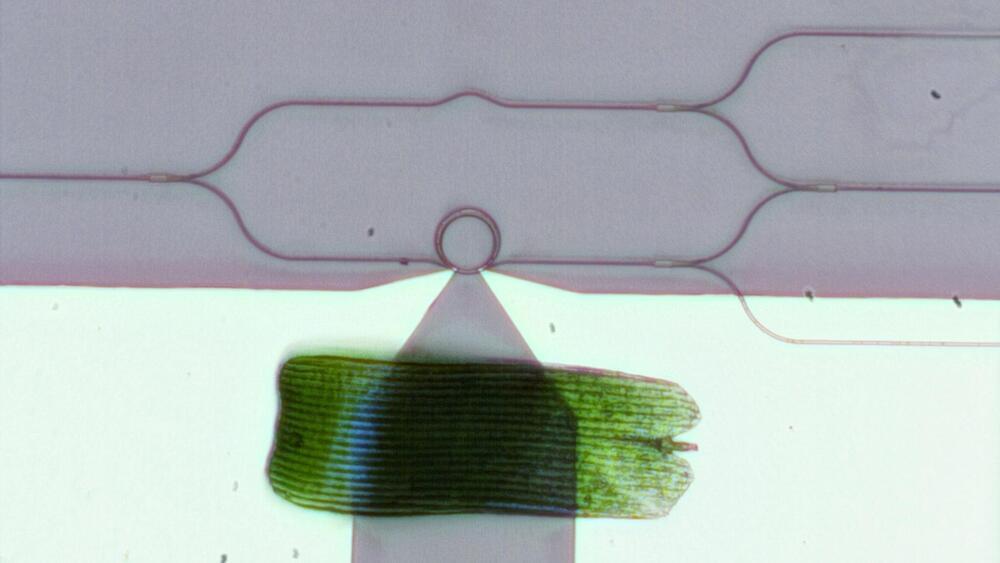

The one device critical to all these applications in the visible range is an optical phase modulator, which controls the phase of a light wave, similar to how the phase of radio waves is modulated in wireless computer networks. With a phase modulator, researchers can build an on-chip optical switch that channels light into different waveguide ports. With a large network of these optical switches, researchers could create sophisticated integrated optical systems that could control light propagating on a tiny chip or light emission from the chip.

But phase modulators in the visible range are very hard to make: there are no materials that are transparent enough in the visible spectrum while also providing large tunability, either through thermo-optical or electro-optical effects. Currently, the two most suitable materials are silicon nitride and lithium niobate. While both are highly transparent in the visible range, neither one provides very much tunability. Visible-spectrum phase modulators based on these materials are thus not only large but also power-hungry: the length of individual waveguide-based modulators ranges from hundreds of microns to several mm and a single modulator consumes tens of mW for phase tuning. Researchers trying to achieve large-scale integration—embedding thousands of devices on a single microchip—have, up to now, been stymied by these bulky, energy-consuming devices.