See more.

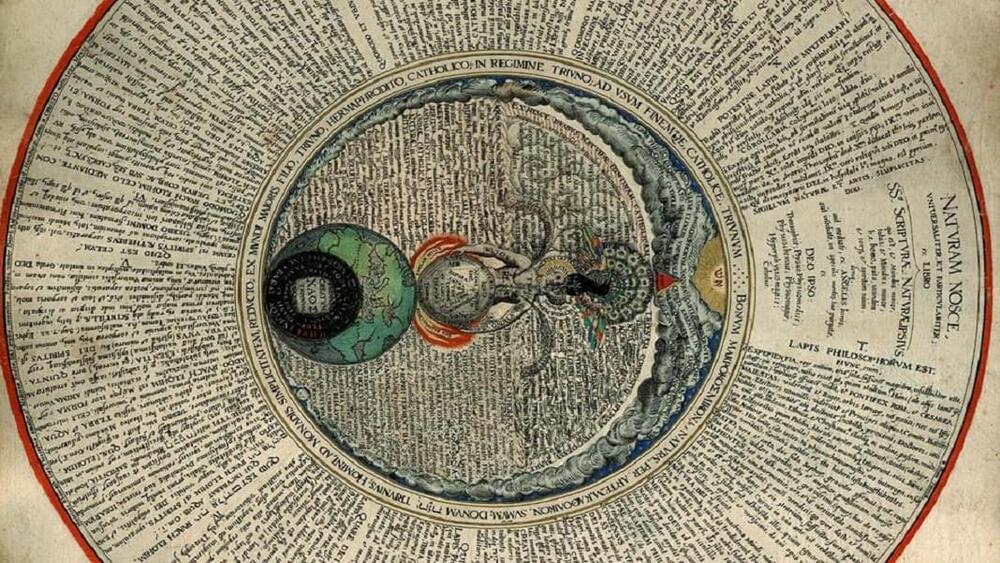

At the conference, Science History Institute postdoctoral researcher Megan Piorko presented a curious manuscript belonging to English alchemists John Dee (1527–1608) and his son Arthur Dee (1579–1651). In the pre-modern world, alchemy was a means to understand nature through ancient secret knowledge and chemical experiment.

Within Dee’s alchemical manuscript was a cipher table, followed by encrypted ciphertext under the heading “Hermeticae Philosophiae medulla”—or Marrow of the Hermetic Philosophy. The table would end up being a valuable tool in decrypting the cipher, but could only be interpreted correctly once the hidden “key” was found.

It was during post-conference drinks in a dimly lit bar that Megan decided to investigate the mysterious alchemical cipher—with the help of her colleague, University of Graz postdoctoral researcher Sarah Lang.

Robotic hand manipulates thousands of objects with ease: bit.ly/3bI367h

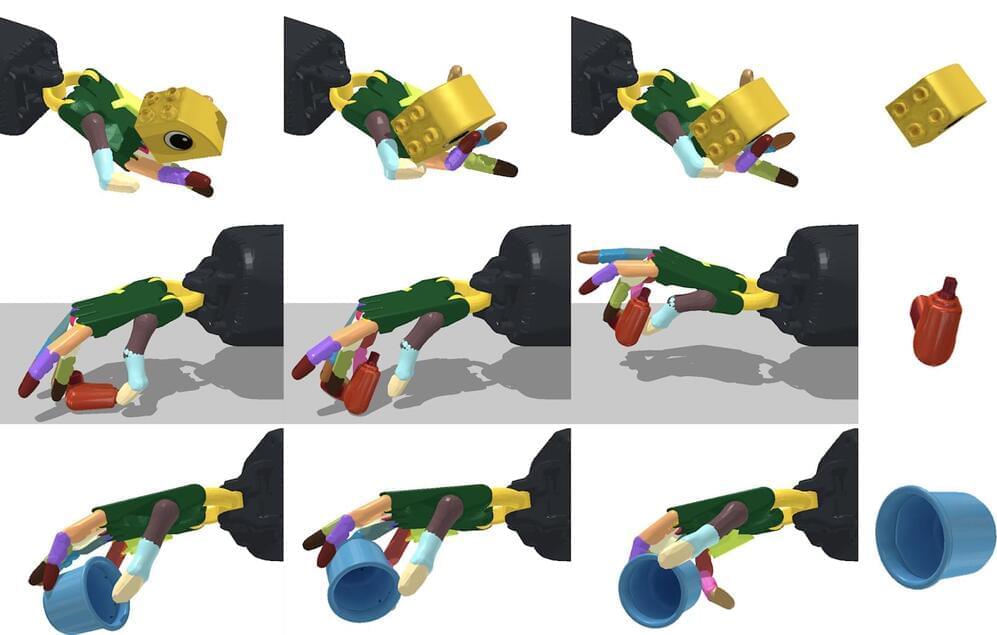

At just one year old, a baby is more dexterous than a robot. Sure, machines can do more than just pick up and put down objects, but we’re not quite there as far as replicating a natural pull towards exploratory or sophisticated dexterous manipulation goes.

OpenAI gave it a try with “Dactyl” (meaning “finger” from the Greek word daktylos), using their humanoid robot hand to solve a Rubik’s cube with software that’s a step towards more general AI, and a step away from the common single-task mentality. DeepMind created “ RGB-Stacking ‚” a vision-based system that challenges a robot to learn how to grab items and stack them.

Scientists from MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL), in the ever-present quest to get machines to replicate human abilities, created a framework that’s more scaled up: a system that can reorient over two thousand different objects, with the robotic hand facing both upwards and downwards. This ability to manipulate anything from a cup to a tuna can, and a Cheez-It box, could help the hand quickly pick-and-place objects in specific ways and locations — and even generalize to unseen objects.

Circa 2015 what if we didn’t need computers we only needed our minds upgraded? Quantum cognition talks about a theory of an upgraded mind.

What type of probability theory best describes the way humans make judgments under uncertainty and decisions under conflict? Although rational models of cognition have become prominent and have achieved much success, they adhere to the laws of classical probability theory despite the fact that human reasoning does not always conform to these laws. For this reason we have seen the recent emergence of models based on an alternative probabilistic framework drawn from quantum theory. These quantum models show promise in addressing cognitive phenomena that have proven recalcitrant to modeling by means of classical probability theory. This review compares and contrasts probabilistic models based on Bayesian or classical versus quantum principles, and highlights the advantages and disadvantages of each approach.

Scheduled to break ground next year, the project will feature 100 single-story houses “printed” on-site using advanced robotic construction and a concrete-based building material.

Digital renderings of the neighborhood, unveiled last week, show rows of properties with their roofs covered in solar cells. The homes will each take approximately a week to build, according to firms behind the development.

The project is a collaboration between homebuilding company Lennar and ICON, a Texas-based construction firm specializing in 3D-printed structures. The houses have been co-designed by the Danish architecture practice Bjarke Ingels Group.

This follows on from an earlier talk I posted by John Cleese (of Monty Python fame) on creativity in business. Mr. Cleese has many great talks on that as he did a tour for his book on creativity. Here Peter Thiel deals with a variety of topics like innovation, trends in business, the stagnation of most technology sectors (no, tech doesn’t just mean computers and consumer gadgets… that a narrow industry is now referred to as the “tech sector” should worry people), many topics… See more.

Speaking with Wired magazine editor David Rowan in London at an event on 25 September, Thiel said that “uniqueness”, “secrets”, and a monopoly on the marketplace were the key to successful startups.

CONNECT WITH WIRED

Web: http://po.st/VideoWired.

Twitter: http://po.st/TwitterWired.

Facebook: http://po.st/FacebookWired.

Google+: http://po.st/GoogleWired.

Instagram: http://po.st/InstagramWired.

Magazine: http://po.st/MagazineWired.

Newsletter: http://po.st/NewslettersWired.

ABOUT WIRED

WIRED brings you the future as it happens — the people, the trends, the big ideas that will change our lives. An award-winning printed monthly and online publication. WIRED is an agenda-setting magazine offering brain food on a wide range of topics, from science, technology and business to pop-culture and politics.

Peter Thiel: Successful businesses are based on secrets | WIRED