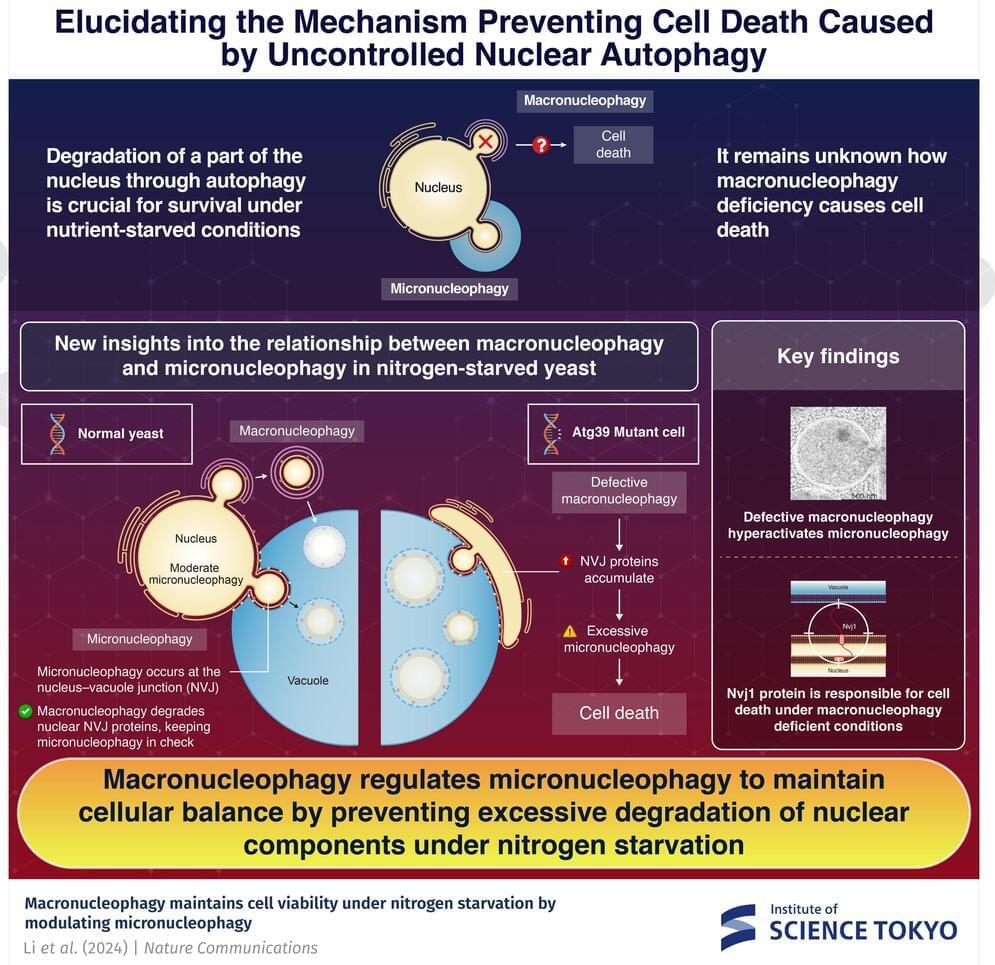

Autophagy, the cell’s essential housekeeping process, involves degrading and recycling damaged organelles, proteins, and other components to prevent clutter. This vital mechanism, found in all life forms from single-celled organisms to plants and animals, is key to maintaining cellular homeostasis. Its disruption is linked to many known diseases in humans, such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and cancer.

Though understanding autophagy in detail is important from medical and biological perspectives, it is not a one-size-fits-all process. There are several forms of autophagy that differ in how the components to be degraded are transported to the lysosomes or vacuoles—the organelles that serve as the cell’s waste disposal and recycling centers.

Autophagy targets a range of intracellular components, including a part of the nucleus that stores important chromosomes. However, the physiological significance of autophagic degradation of the nucleus remains unknown.