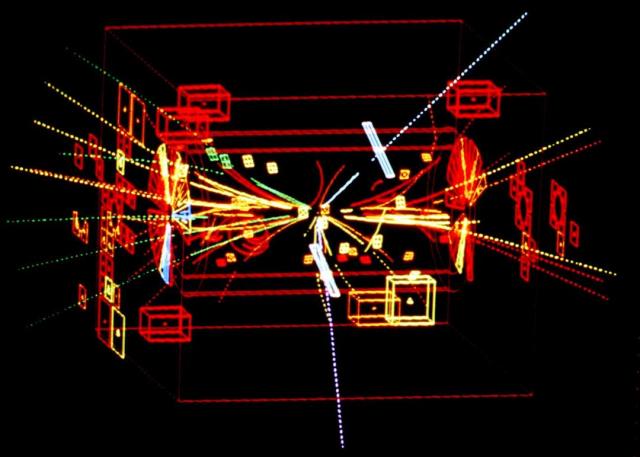

Time travel movies have different rules about what happens when you start messing around with the timeline. If you’ve ever wondered which ones make the most sense, we may now have an answer. According to experiments using a quantum time travel simulator, reality is more or less “self-healing,” so changes made to the past won’t drastically alter the future you came from – at least, in the quantum realm.

The classic Back to the Future rules of time travel say that whatever you change in the past can have huge effects on the future. That’s why Marty McFly can almost erase his own existence by accidentally stopping his parents from meeting, and why Biff Tannen can get rich by giving his younger self a book of sports scores to bet on.

Other movies handle things differently. In Avengers: Endgame, the superheroes travel back in time to steal versions of the Infinity Stones out of different time periods to revive their fallen friends (look, it doesn’t make much sense unless you’ve seen all 20-something movies). Anyway, they can dabble in the past without ruining the future because the universe has a knack for correcting those paradoxes so that both versions of events did happen.