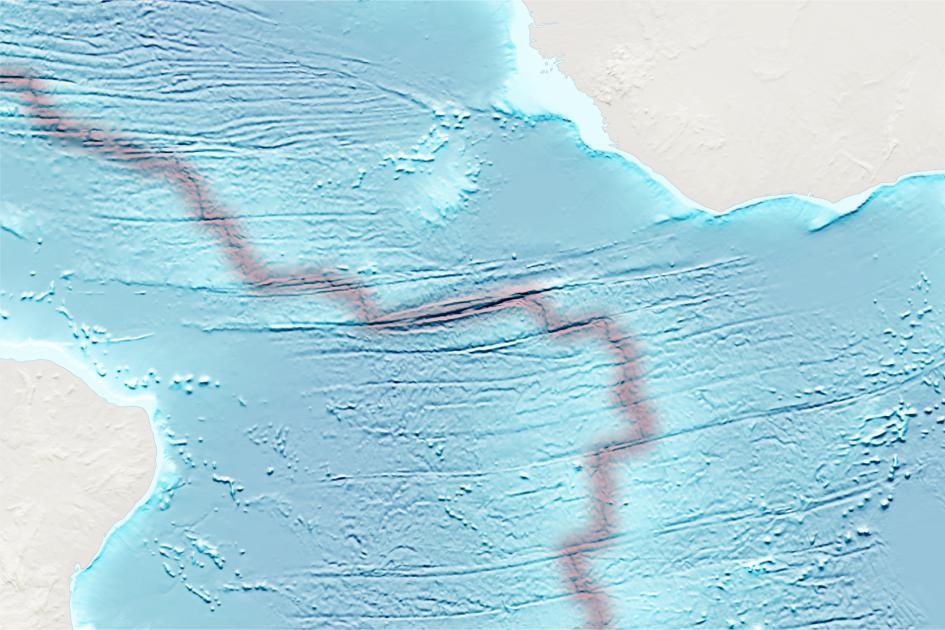

This magnitude 7.1 earthquake started deep underground, in a gash on the Atlantic seafloor, a little more than 650 miles off the coast of Liberia, in western Africa. It rushed eastward and upward, then did an about-face and boomeranged back along the upper section of the fault at incredible speeds‑so fast it caused the geologic version of a sonic boom.

The ferocity of shaking from an earthquake is usually focused in the direction the temblor is traveling. But a boomerang quake, or a “back-propagating rupture” in scientific terms, may spread the intense shaking across a wider zone. It remains uncertain how common boomerang earthquakes are—and how many travel at such great speeds. But the new study, published today in the journal Nature Geoscience, is a major step toward untangling the complex physics behind these events and understanding their potential hazards.

“Studies like this help us understand how past earthquakes ruptured, how future earthquakes may rupture, and how that relates to the potential impact for faults near populated areas,” says Kasey Aderhold, a seismologist with the Incorporated Research Institutions for Seismology, via email.