The newly developed device captures moments a quintillionth of a second long.

Get the latest international news and world events from around the world.

Delivering 1.5 M TPS Inference on NVIDIA GB200 NVL72, NVIDIA Accelerates OpenAI gpt-oss Models from Cloud to Edge

NVIDIA and OpenAI began pushing the boundaries of AI with the launch of NVIDIA DGX back in 2016. The collaborative AI innovation continues with the OpenAI gpt-oss-20b and gpt-oss-120b launch. NVIDIA has optimized both new open-weight models for accelerated inference performance on NVIDIA Blackwell architecture, delivering up to 1.5 million tokens per second (TPS) on an NVIDIA GB200 NVL72 system.

The gpt-oss models are text-reasoning LLMs with chain-of-thought and tool-calling capabilities using the popular mixture of experts (MoE) architecture with SwigGLU activations. The attention layers use RoPE with 128k context, alternating between full context and a sliding 128-token window. The models are released in FP4 precision, which fits on a single 80 GB data center GPU and is natively supported by Blackwell.

The models were trained on NVIDIA H100 Tensor Core GPUs, with gpt-oss-120b requiring over 2.1 million hours and gpt-oss-20b about 10x less. NVIDIA worked with several top open-source frameworks such as Hugging Face Transformers, Ollama, and vLLM, in addition to NVIDIA TensorRT-LLM for optimized kernels and model enhancements. This blog post showcases how NVIDIA has integrated gpt-oss across the software platform to meet developers’ needs.

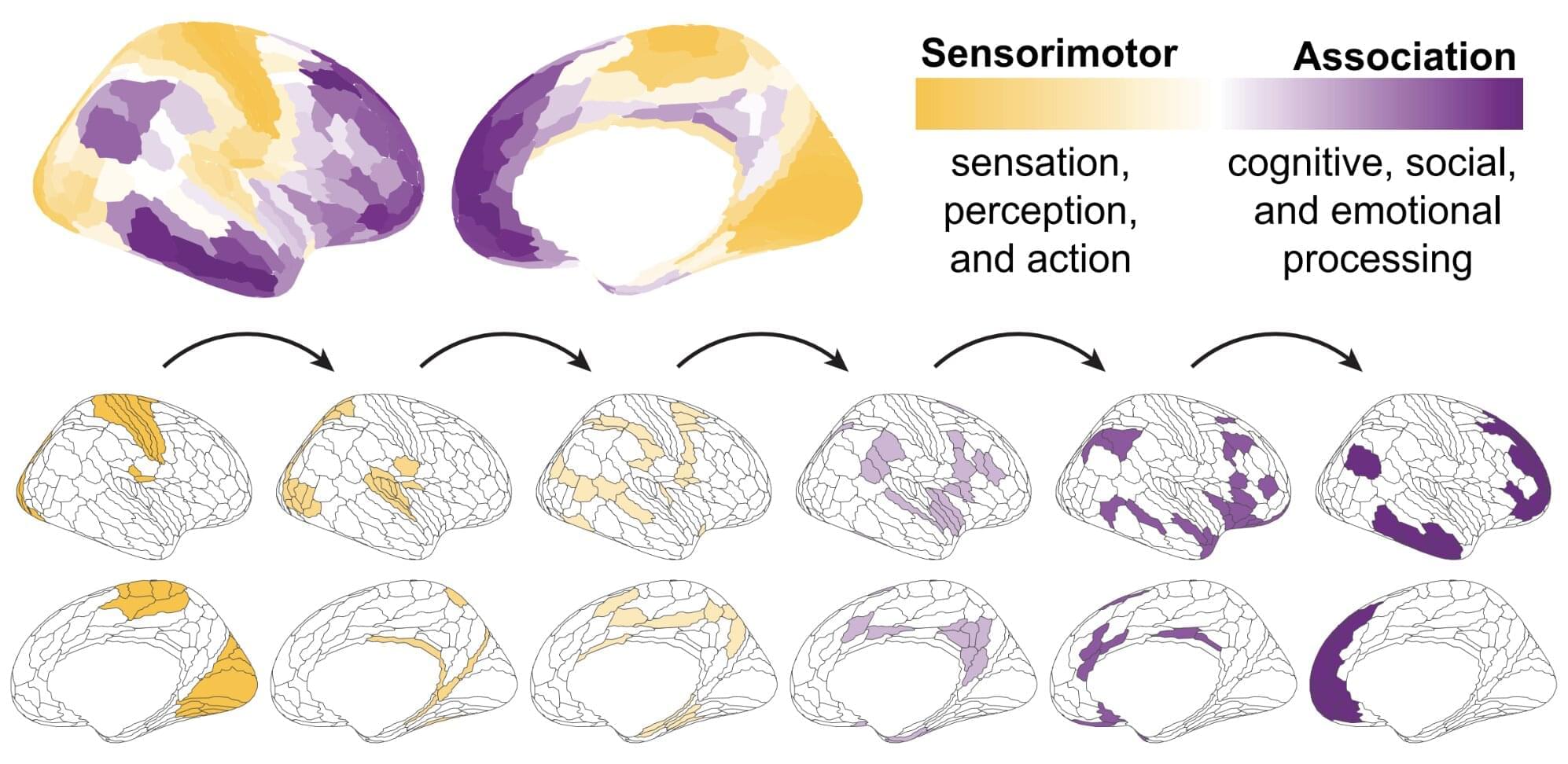

More than a simple relay station: Thalamus may guide timing of brain development and plasticity

The brain is known to develop gradually throughout the human lifespan, following a hierarchical pattern. First, it adapts to support basic functions, such as movement and sensory perception, then it moves onto more advanced human abilities, such as decision-making.

Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania and other institutes, led by Principal Investigator Dr. Theodore Satterthwaite, recently carried out a study aimed at better understanding how the thalamus, a structure deep within the brain known to be involved in the processing and routing of sensory information, could contribute to the brain’s development over time.

Their findings, published in Nature Neuroscience, suggest that the thalamus is more than a relay station for sensory and motor signals, and also plays a role in regulating the hierarchical pattern and timeline of brain development.

Tesla’s New Strategy Has Uber Terrified

Questions to inspire discussion.

👥 Q: What is the ratio of robo taxis to supervisors in Tesla’s network? A: Tesla’s robo taxi network operates with a 10:1 ratio of robo taxis to supervisors, enabling efficient management and cost-effective operations.

Market Disruption.

📊 Q: How is Whim, a Tesla competitor, performing in the market? A: As of April 2025, Whim has 25% of San Francisco gross bookings, surpassing Lyft, with an average price of $20 per mile compared to Uber’s $15 and Lyft’s $14.

Technology Superiority.

🤖 Q: How does Tesla’s robo taxi software compare to human drivers? A: Tesla’s robo taxi software has crossed the uncanny valley, providing a smooth and comfortable driving experience similar to a human chauffeur, outperforming Uber’s inconsistent service.

Traveling to Proxima Centauri B in 100 Years vs 4 Days

This is a sci-fi documentary, looking at 3 different spaceships (nuclear fusion generational spacecraft, cryoship, warp drive) and their different paths to Proxima Centauri B. The video looks at some of the science behind each spacecraft, and how well prepared the passengers arrive at the new planet.

Three journeys venturing far beyond Earth’s solar system, showing the future science of space travel, exploration, and future space technology.

Personal inspiration in creating this video comes from: the movie Interstellar (Endurance), The Expanse TV show (The Nauvoo), and Star Trek Next Generation (The Enterprise).

PATREON

The third volume of ‘The Encyclopedia of the Future’ is now available on my Patreon.

Visit my Patreon here: / venturecity.

–

Cedar Park votes to join Central Texas aerospace corporation

The city council voted to become part of the Central Texas Space Development Corporation.