But the latest iteration of the Noodlophile attacks exhibits notable deviation, particularly when it comes to the use of legitimate software vulnerabilities, obfuscated staging via Telegram, and dynamic payload execution.

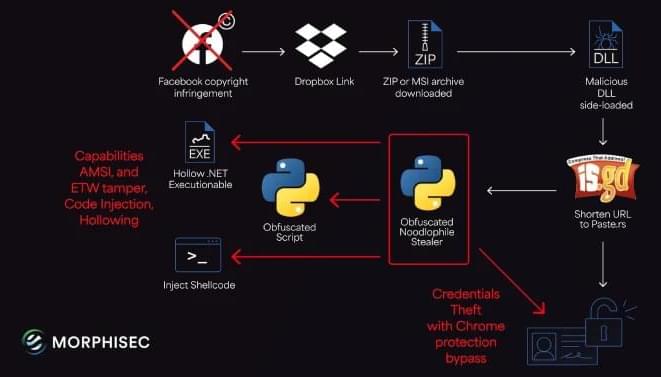

It all starts with a phishing email that seeks to trick employees into downloading and running malicious payloads by inducing a false sense of urgency, claiming copyright violations on specific Facebook Pages. The messages originate from Gmail accounts in an effort to evade suspicion.

Present within the message is a Dropbox link that drops a ZIP or MSI installer, which, in turn, sideloads a malicious DLL using legitimate binaries associated with Haihaisoft PDF Reader to ultimately launch the obfuscated Noodlophile stealer, but not before running batch scripts to establish persistence using Windows Registry.