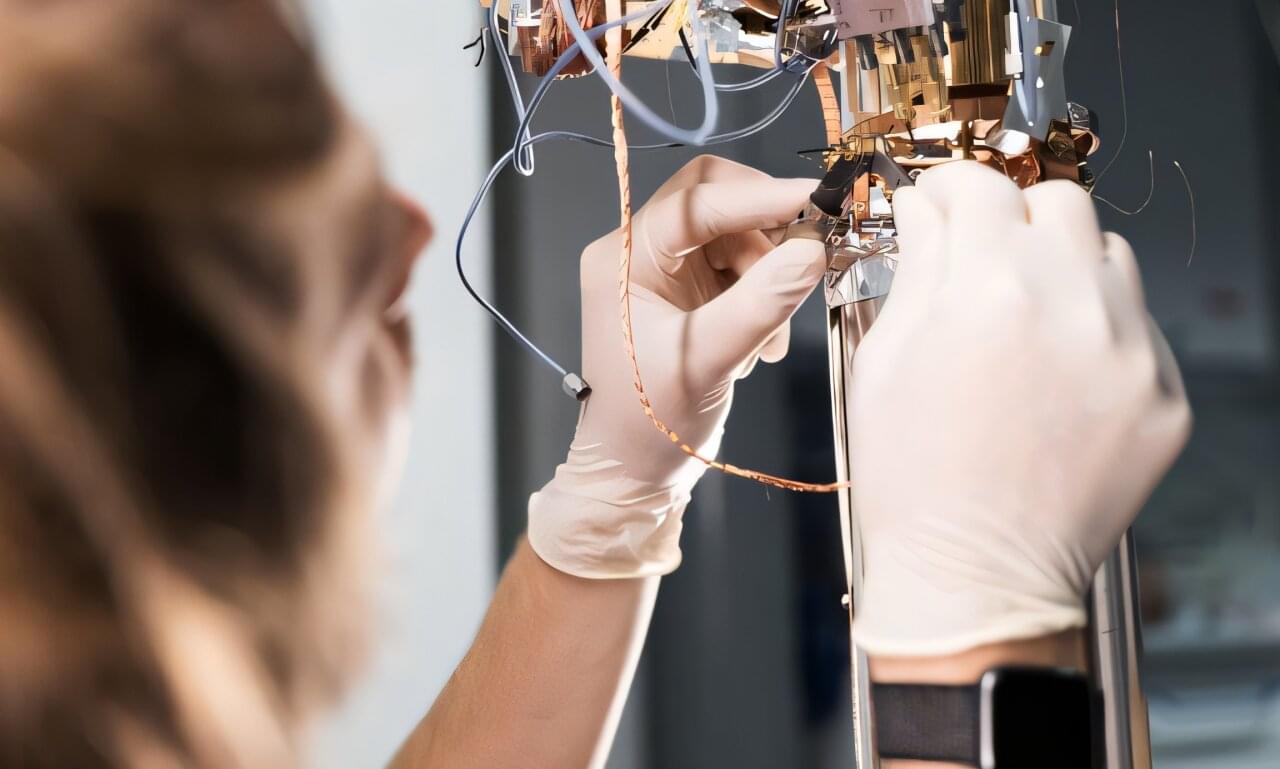

Innsbruck physicists have presented a new architecture for improved quantum control of microwave resonators. In a study recently published in PRX Quantum, they show how a superconducting fluxonium qubit can be selectively coupled and decoupled with a microwave resonator and without additional components. This makes potentially longer storage times possible.

Microwave resonators are considered a promising building block for the development of robust quantum computers, as they store quantum information in more complex states. This simplifies error correction and allows significantly longer storage times.

“The storage time of quantum information of these microwave resonators has so far been limited by undesirable interactions with the superconducting qubits used to control them,” explains Gerhard Kirchmair from the Department of Experimental Physics at the University of Innsbruck and the Institute of Quantum Optics and Quantum Information (IQOQI) of the Austrian Academy of Sciences.