Observation of temporal reflection and broadband frequency translation at photonic time interfaces https://www.nature.com/articles/s41567-023-01975-y

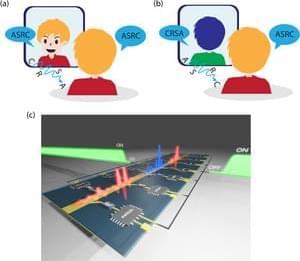

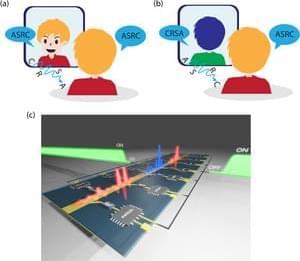

NEW YORK, March 13, 2023 — When we look in a mirror, we are used to seeing our faces looking back at us. The reflected images are produced by electromagnetic light waves bouncing off of the mirrored surface, creating the common phenomenon called spatial reflection. Similarly, spatial reflections of sound waves form echoes that carry our words back to us in the same order we spoke them.

Scientists have hypothesized for over six decades the possibility of observing a different form of wave reflections, known as temporal, or time, reflections. In contrast to spatial reflections, which arise when light or sound waves hit a boundary such as a mirror or a wall at a specific location in space, time reflections arise when the entire medium in which the wave is traveling suddenly and abruptly changes its properties across all of space. At such an event, a portion of the wave is time reversed, and its frequency is converted to a new frequency.

To date, this phenomenon had never been observed for electromagnetic waves. The fundamental reason for this lack of evidence is that the optical properties of a material cannot be easily changed at a speed and magnitude that induces time reflections. Now, however, in a newly published paper in Nature Physics, researchers at the Advanced Science Research Center at the CUNY Graduate Center (CUNY ASRC) detail a breakthrough experiment in which they were able to observe time reflections of electromagnetic signals in a tailored metamaterial.