NewsPicks crew flew to Canada in search of AI revolution but unexpectedly came across the true story behind the birth of AI.

Get the latest international news and world events from around the world.

Revisiting the IPIP-NEO Personality Hierarchy with Taxonomic Graph Analysis

Describing and understanding personality structure is fundamental to predict and explain human behavior. Recent research calls for large personality item pools to be analyzed from the bottom-up, as item-level analysis may reveal meaningful differences often obscured by aggregation. This study introduces and applies Taxonomic Graph Analysis (TGA), a comprehensive network psychometrics framework aimed at identifying hierarchical structures in personality from the bottom-up, to an open-source 300-item IPIP-NEO dataset (N = 149,337). This framework addresses key methodological challenges that have hindered accurate recovery of hierarchical structures, including local independence violations, wording effects, dimensionality assessment, and structural robustness.

The Case for Life on Mars Just Got Stronger

“This finding by Perseverance …is the closest we have ever come to discovering life on Mars,” said acting NASA administrator Sean Duffy in a statement. “The identification of a potential biosignature on the Red Planet is a groundbreaking discovery, and one that will advance our understanding of Mars.”

Perseverance did not discover fossilized microbes and it surely didn’t discover living ones. What it found was a rock streaked in a range of colors—red, green, purple, and blue—flecked with poppy-seed-like dots and decorated with what the Perseverance scientists compared to dull yellow leopard spots. That said a lot. As the rover’s instruments confirmed, the red is iron-rich mud, the purple is iron and phosphorous, the yellow and green are iron and sulfur. All of those elements serve as something of a chow line for hungry microbes.

The poppy seeds and leopard spots, meantime, resemble markings left behind by metabolizing microbes on Earth. When the rover trained its instruments on those features they detected two iron-rich minerals—vivianite and greigite. On Earth, vivianite is frequently found in peat bogs and around decaying organic matter—another item on the microbes’ menu. And both minerals can be produced by microbial life. Images of the rock with its distinctive features were beamed back to Earth by Perseverance, while X-ray and laser sensors analyzed the chemistry of the markings.

The AI Takeover Is Closer Than You Think

To try Brilliant for free, visit https://brilliant.org/APERTURE/ or scan the QR code onscreen. You’ll also get 20% off an annual premium subscription.

AI experts from all around the world believe that given its current rate of progress, by 2027, we may hit the most dangerous milestone in human history. The point of no return, when AI could stop being a tool and start improving itself beyond our control. A moment when humanity may never catch up.

00:00 The AI Takeover Is Closer Than You Think.

01:05 The rise of AI in text, art & video.

02:00 What is the Technological Singularity?

04:06 AI’s impact on jobs & economy.

05:31 What happens when AI surpasses human intellect.

08:36 AlphaGo vs world champion Lee Sedol.

11:10 Can we really “turn off” AI?

12:12 Narrow AI vs Artificial General Intelligence (AGI)

16:39 AGI (Artificial General Intelligence)

18:01 From AGI to Superintelligence.

20:18 Ethical concerns & defining intelligence.

22:36 Neuralink and human-AI integration.

25:54 Experts warning of 2027 AGI

Support: / apertureyt.

Shop: https://bit.ly/ApertureMerch.

Subscribe: https://bit.ly/SubscribeToAperture.

Discord: / discord.

Questions or concerns? https://underknown.com/contact/

Interested in sponsoring Aperture? [email protected].

#aperture #ai #artificialintelligence #pointofnoreturn #technology #tech #future

6 Ways Aliens Could Find Us

Whether or not you think humans *should* be announcing our presence to the cosmos, we’re doing it, anyway. Both intentionally, and not. And if aliens really…

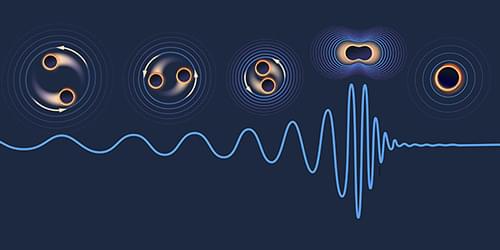

Landmark Black Hole Test Marks Decade of Gravitational-Wave Discoveries

The clearest black hole merger signal ever measured has allowed researchers to test the Kerr nature of black holes and validate Stephen Hawking’s black hole area theorem.

Gravitational-wave astronomy is moving at breakneck speed. Just over a decade ago, the direct detection of gravitational waves was considered an elusive goal—perpetually said to be “five-to-ten years away.” Then came the 2015 breakthrough: the first observed merger of two black holes, known as GW150914 [1]. Detections have since become routine, with a catalog of black hole mergers now numbering in the hundreds. There is even evidence for a gravitational-wave background at nanohertz frequencies, plausibly sourced by a population of supermassive black hole binaries throughout the Universe. Now the LIGO detectors have captured the clearest merger signal ever recorded, GW250114 [2]. From such a signal, the LIGO-Virgo-KAGRA (LVK) Collaboration was able to draw two spectacular conclusions. First, it confirmed that the nature of the merging objects is consistent with that of Kerr (spinning) black holes.

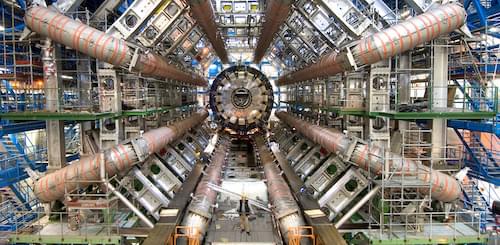

Probing the Higgs Mechanism with Particle Collisions and AI

A deep neural network has proven essential in confirming a key prediction of one of the standard model’s cornerstones.

The Higgs mechanism explains why the electromagnetic and weak interactions have such drastically different strengths—that is, how their symmetry became broken a picosecond after the big bang. The Higgs does not interact with photons, rendering them massless, whereas they do interact with the carriers of the weak interaction (the W+, W–, and Z bosons), giving them masses of order 100 GeV. Their nonzero masses allow them to acquire a longitudinal polarization—that is, a spin orientation perpendicular to their direction of motion. Because of special relativity, photons and other massless bosons that travel at the speed of light can’t have longitudinal polarization, but the W and Z bosons and other massive particles can. If electroweak symmetry had been broken not by the Higgs mechanism but by a different interaction, there would be no Higgs boson to find.

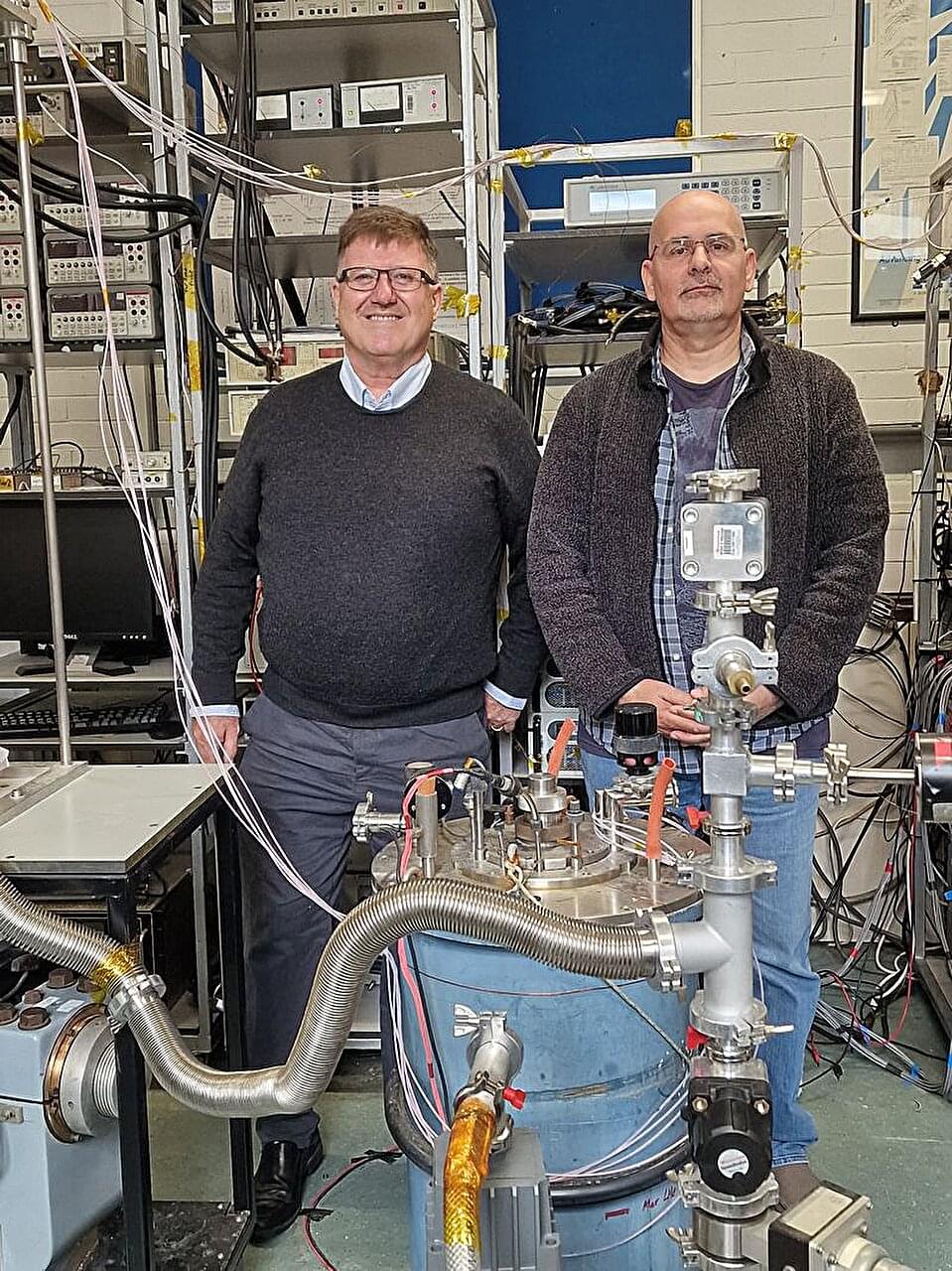

Tests on superconducting materials for world’s largest fusion energy project show reliable measurement protocol

Durham University scientists have completed one of the largest quality verification programs ever carried out on superconducting materials, helping to ensure the success of the world’s biggest fusion energy experiment ITER.

Their findings, published in Superconductor Science and Technology, shed light not only on the quality of the wires themselves but also on how to best test them, providing crucial knowledge for scientists to make fusion energy a reality.

Fusion (the process that powers the sun) has long been described as the holy grail of clean energy. It offers the promise of a virtually limitless power source with no carbon emissions and minimal radioactive waste.