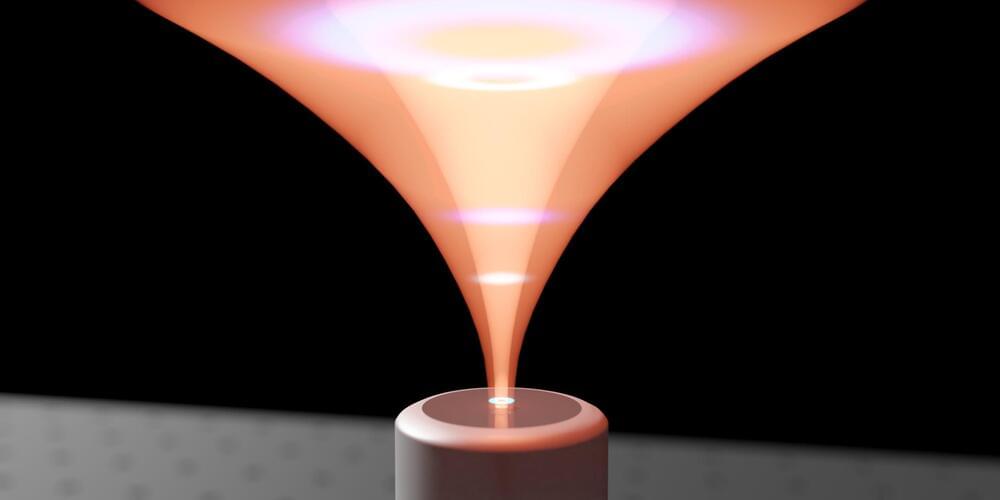

Optics, the study of light, is one of the oldest fields in physics and has never ceased to surprise researchers. Although the classical description of light as a wave phenomenon is rarely questioned, the physical origins of some optical effects are. A team of researchers at Tampere University have brought the discussion on one fundamental wave effect, the debate around the anomalous behavior of focused light waves, to the quantum domain.

The researchers have been able to show that quantum waves behave significantly differently from their classical counterparts and can be used to increase the precision of distance measurements. Their findings also add to the discussion on physical origin of the anomalous focusing behavior. The results are now published in Nature Photonics.

“Interestingly, we started with an idea based on our earlier results and set out to structure quantum light for enhanced measurement precision. However, we then realized that the underlying physics of this application also contributes to the long debate about the origins of the Gouy phase anomaly of focused light fields,” explains Robert Fickler, group leader of the Experimental Quantum Optics group at Tampere University.