A groundbreaking interdisciplinary study by Tel Aviv University (TAU) and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem (HU) involving 20 international scientists and researchers has verified biblical accounts of the Egyptian, Aramean, Assyrian and Babylonian military campaigns against the kingdoms of Israel and Judah.

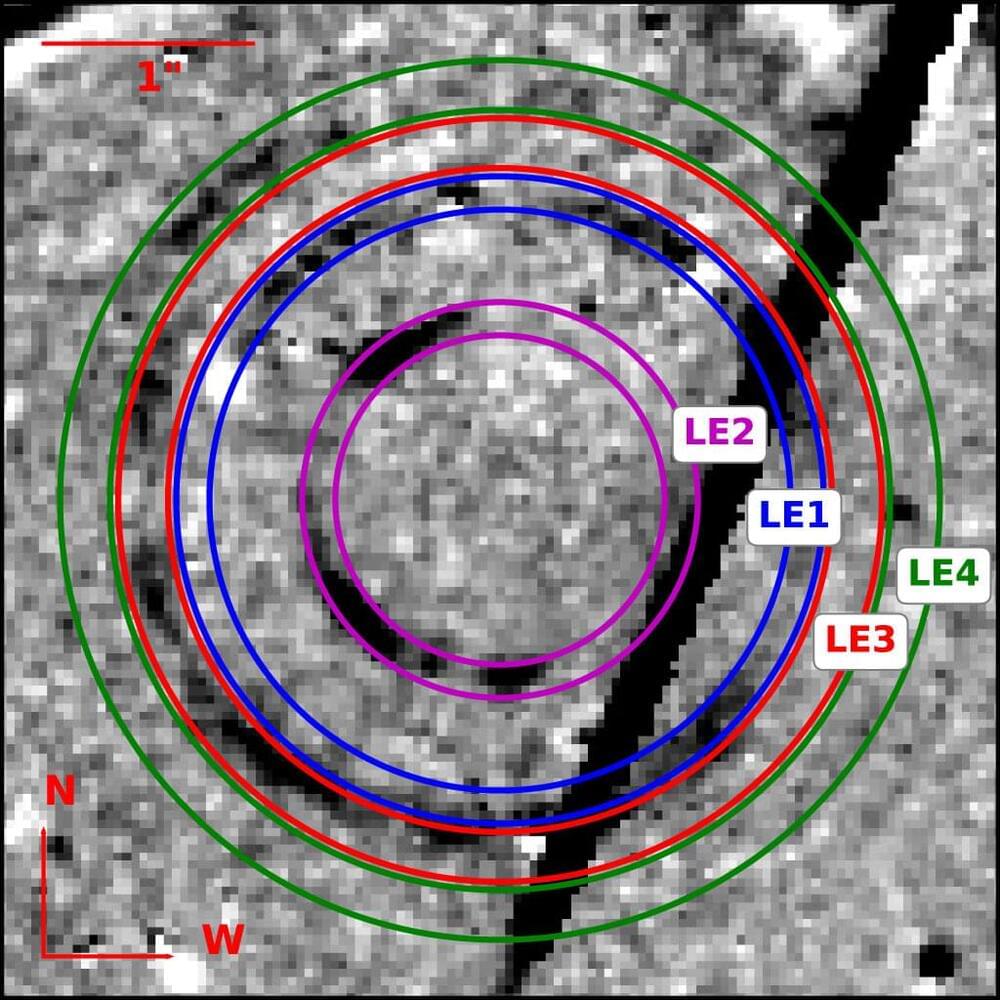

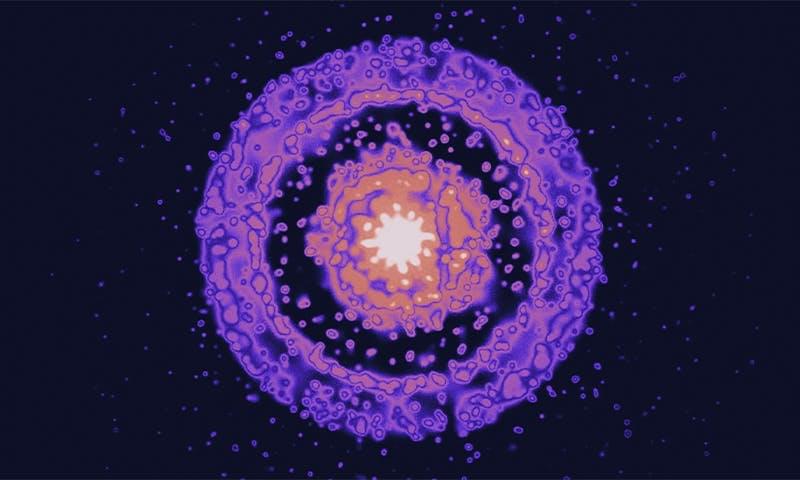

The study reconstructed changes in the magnetic field of the earth as recorded in 21 destruction layers in 17 archeological sites throughout Israel, constructing a variation curve of field intensity over time that can be used as a scientific dating tool.

Published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), the study is based on the doctoral thesis of Yoav Vaknin, and supervised by Prof. Erez Ben-Yosef and Prof. Oded Lipschits of TAU’s Institute of Archaeology, and Prof. Ron Shaar of HU’s Institute of Earth Sciences.