SpaceX’s Starlink satellite internet service has let the company capture high definition video of its rocket landing on a ship.

Little is known about the ancient Mittani people who built the city, largely due to the fact that researchers have not identified the empire’s capital or discovered their archives, Puljiz said. However, certain artifacts unearthed during the latest excavation could help provide insight.

Archaeologists found five ceramic vessels holding over 100 clay cuneiform tablets, dating back to closely after the earthquake event. They are believed to be from the Middle Assyrian period, which lasted from 1,350 to 1,100 BC, and could shed light on the city’s demise and the rise of Assyrian rule in the area, according to a news release.

“It is close to a miracle that cuneiform tablets made of unfired clay survived so many decades under water,” said Peter Pfälzner, professor of near eastern archaeology at University of Tübingen and one of the excavation directors, in a statement.

Dr. Michael Salla

This is the official trailer/short film for the “Time Travel, Temporal Warfare & Our Future” webinar to be held on July 2, 2022. Covers the historical development of time travel technology in Germany and the United States, and how it has been used in a temporal war by different factions of humans and extraterrestrial organizations. Explains how humanity was manipulated through time travel technology, and how that is about to end as we enter a new period in human development due to the arrival of ET Seeder races.

The human middle ear—which houses three tiny, vibrating bones—is key to transporting sound vibrations into the inner ear, where they become nerve impulses that allow us to hear.

Embryonic and fossil evidence proves that the human middle ear evolved from the spiracle of fishes. However, the origin of the vertebrate spiracle has long been an unsolved mystery in vertebrate evolution.

“These fossils provided the first anatomical and fossil evidence for a vertebrate spiracle originating from fish gills.” —

Tricarboxylic acid cycle/kreb cycle/citric acid cycle.

#citricacidcycle #krebs #biochemistry #biology #Cellular #respiration

This Video Explains Tricarboxylic Acid Cycle/Kreb Cycle/Citric Acid Cycle.

Thank You For Watching.

Please Like And Subscribe to Our Channel: https://www.youtube.com/EasyPeasyLearning.

Like Our Facebook Page: https://www.facebook.com/learningeasypeasy/

Join Our Facebook Group: https://www.facebook.com/groups/460057834950033

Support Our Channel: https://www.patreon.com/supereasypeasy

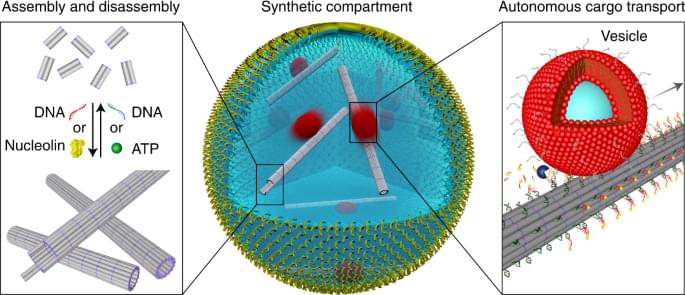

Cytoskeletons are essential components of cells that perform a variety of tasks, and artificial cytoskeletons that perform these functions are required for the bottom-up assembly of synthetic cells. Now, a multi-functional cytoskeleton mimic has been engineered from DNA, consisting of confined DNA filaments that are capable of reversible self-assembly and transport of gold nanoparticles and vesicular cargo.

Researching Non-Specific Vaccine Effects For Human Health Benefit — Prof. Dr. Christine Stabell Benn, MD, PhD, DMSc, University Of Southern Denmark

Prof. Dr. Christine Stabell Benn, MD, PhD, DMSc, (https://portal.findresearcher.sdu.dk/en/persons/cbenn), is a physician, a professor of global health at the University of Southern Denmark, and a vaccine researcher with almost thirty years of experience in the field, where the focus of her research is “non-specific vaccine effects”, defined as all those other effects, both positive and negative, that vaccines have on our immune systems and overall health, beyond their very specific ability to protect against a specific infectious disease.

Prof. Dr. Stabell Benn has her medical degree, PhD, and Doctor of Medical Science from University of Copenhagen and has been responsible for planning, executing and publishing epidemiological and immunological studies of health interventions internationally, as well as supervising a number of pre-and postgraduate/PhD students.

Prof. Dr. Stabell Benn started working as a medical student in 1993 at the Bandim Health Project (https://www.bandim.org/), a population based health research project in one of the world’s poorest countries, Guinea-Bissau, developing a health and demographic surveillance system of over 100,000 people. She spent postdoc time at the Danish National Hospital, Department for Infectious Diseases and at Stanford University.

In 2012, Dr. Benn was selected by the Danish National Research Foundation to establish and lead a Center of Excellence, the “Research Center for Vitamins and Vaccines” (CVIVA — www.cviva.dk).

Based on a novel intertwined theoretical and experimental approach, we examined one of the pillars of the Orch OR model, namely the gravity-related collapse model. In this context, we examined the Orch OR calculations using the gravity-related (called Diosi-Penrose, DP, for reasons we explain in the article) theory along with recent experimental constraints on the DP cutoff parameter (R0). We showed that, in this context, the Orch OR based on the DP theory is definitively ruled out for the case of atomic nuclei level of separation, without needing to consider the impact of environmental decoherence; we also showed that the case of partial separation requires the brain to maintain coherent superpositions of tubulin of such mass, duration, and size that vastly exceed any of the coherent superposition states that have been achieved with state-of-the-art optomechanics and macromolecular interference experiments. We conclude that none of the scenarios we discuss (with possible exception to the case of partial separation of tubulins) are plausible.