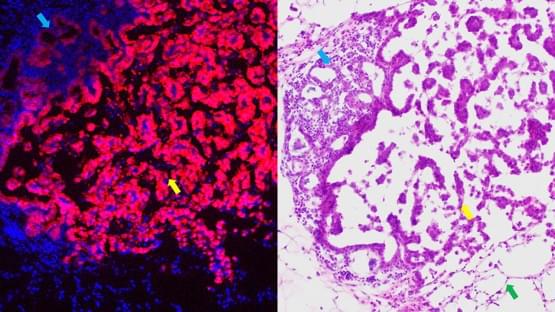

A team of scientists from the Department of Energy’s Ames National Laboratory has developed a new characterization tool that allowed them to gain unique insight into a possible alternative material for solar cells. Under the leadership of Jigang Wang, senior scientist from Ames Lab, the team developed a microscope that uses terahertz waves to collect data on material samples. The team then used their microscope to explore methylammonium lead iodide (MAPbI3) perovskite, a material that could potentially replace silicon in solar cells.

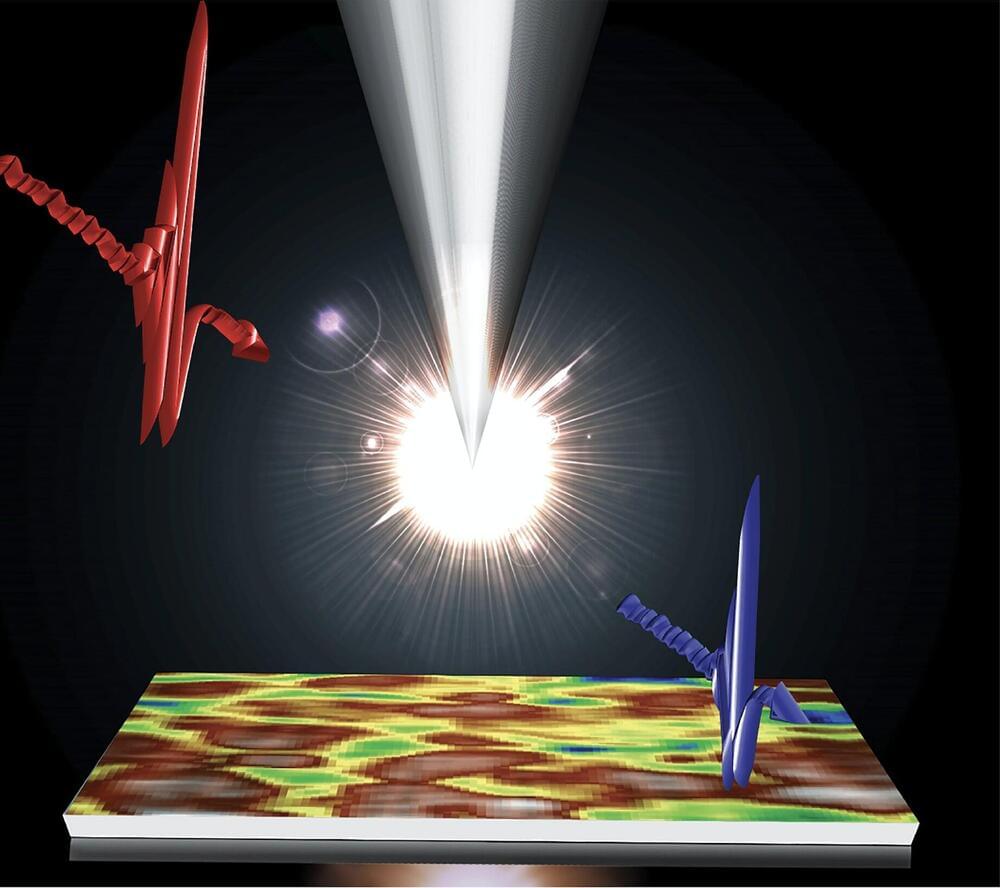

Richard Kim, a scientist from Ames Lab, explained the two features that make the new scanning probe microscope unique. First, the microscope uses the terahertz range of electromagnetic frequencies to collect data on materials. This range is far below the visible light spectrum, falling between the infrared and microwave frequencies. Secondly, the terahertz light is shined through a sharp metallic tip that enhances the microscope’s capabilities toward nanometer length scales.

“Normally if you have a light wave, you cannot see things smaller than the wavelength of the light you’re using. And for this terahertz light, the wavelength is about a millimeter, so it’s quite large,” explained Kim. “But here we used this sharp metallic tip with an apex that is sharpened to a 20-nanometer radius curvature, and this acts as our antenna to see things smaller than the wavelength that we were using.”