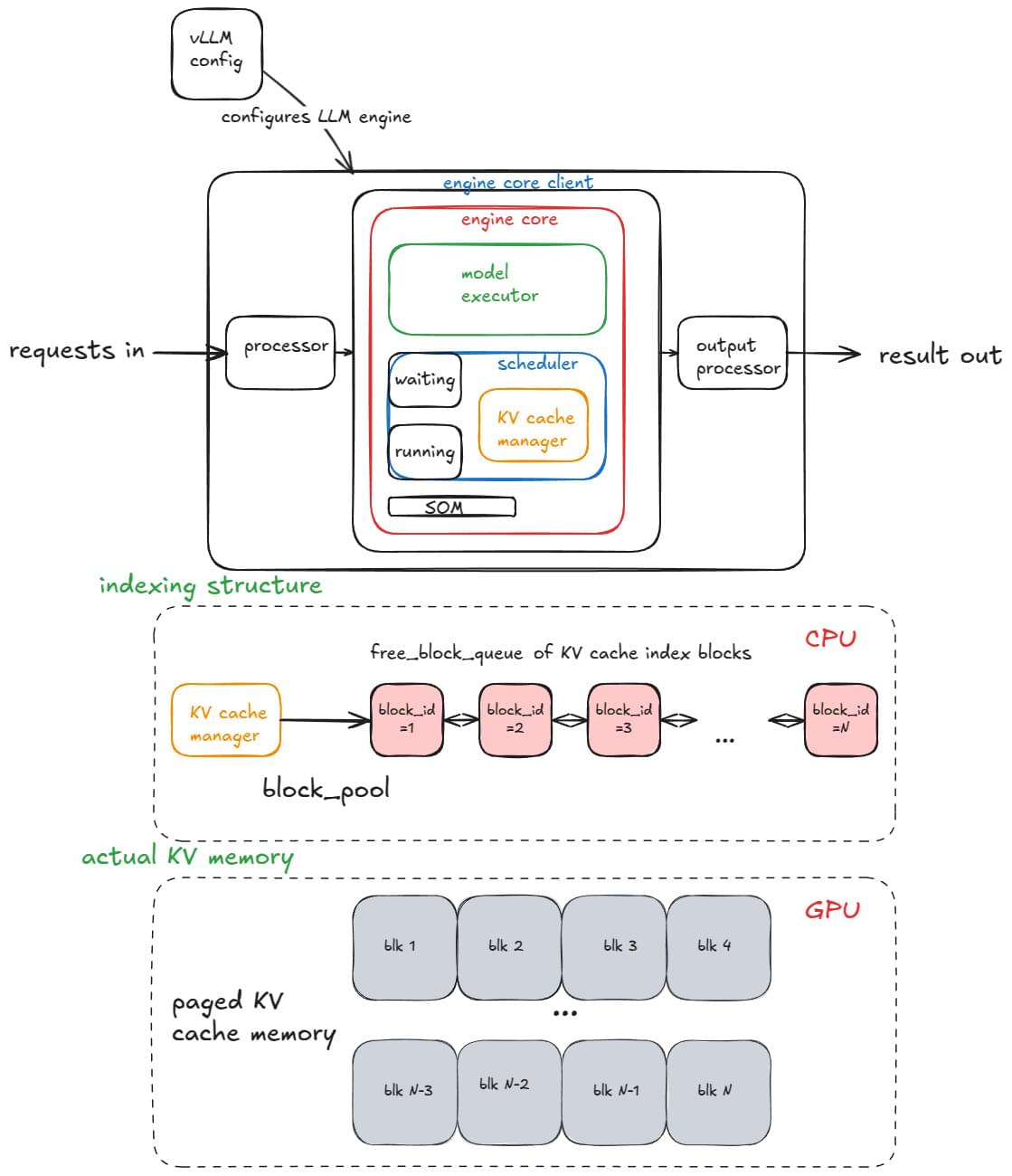

From paged attention, continuous batching, prefix caching, specdec, etc. to multi-GPU, multi-node dynamic serving at scale.

Students at ETH Zurich have developed a laser powder bed fusion machine that follows a circular tool path to print round components, which allows the processing of multiple metals at once. The system significantly reduces manufacturing time and opens up new possibilities for aerospace and industry. ETH has filed a patent application for the machine, and the results are published in the CIRP Annals.

Today, virtually all modern rocket engines rely on 3D printing to maximize their performance with tight coupling between structure and function. Students at ETH Zurich have now built a high-speed multi-material metal printer: a laser powder bed fusion machine that rotates the powder deposition and gas flow nozzles while it prints, which means it can process several metals simultaneously and without process dead time. The machine could fundamentally change the 3D printing of metal parts, resulting in significant reductions in production time and cost.

The team of six Bachelor’s students in their fifth and sixth semesters developed the new machine in the Advanced Manufacturing Lab under the guidance of ETH Professor Markus Bambach and Senior Scientist Michael Tucker as part of the Focus Project RAPTURE. In a mere nine months, the students realized, built and tested their idea. The machine is particularly aimed at applications in aerospace featuring approximately cylindrical geometries, such as rocket nozzles and turbomachinery, but is also of broad interest for mechanical engineering.

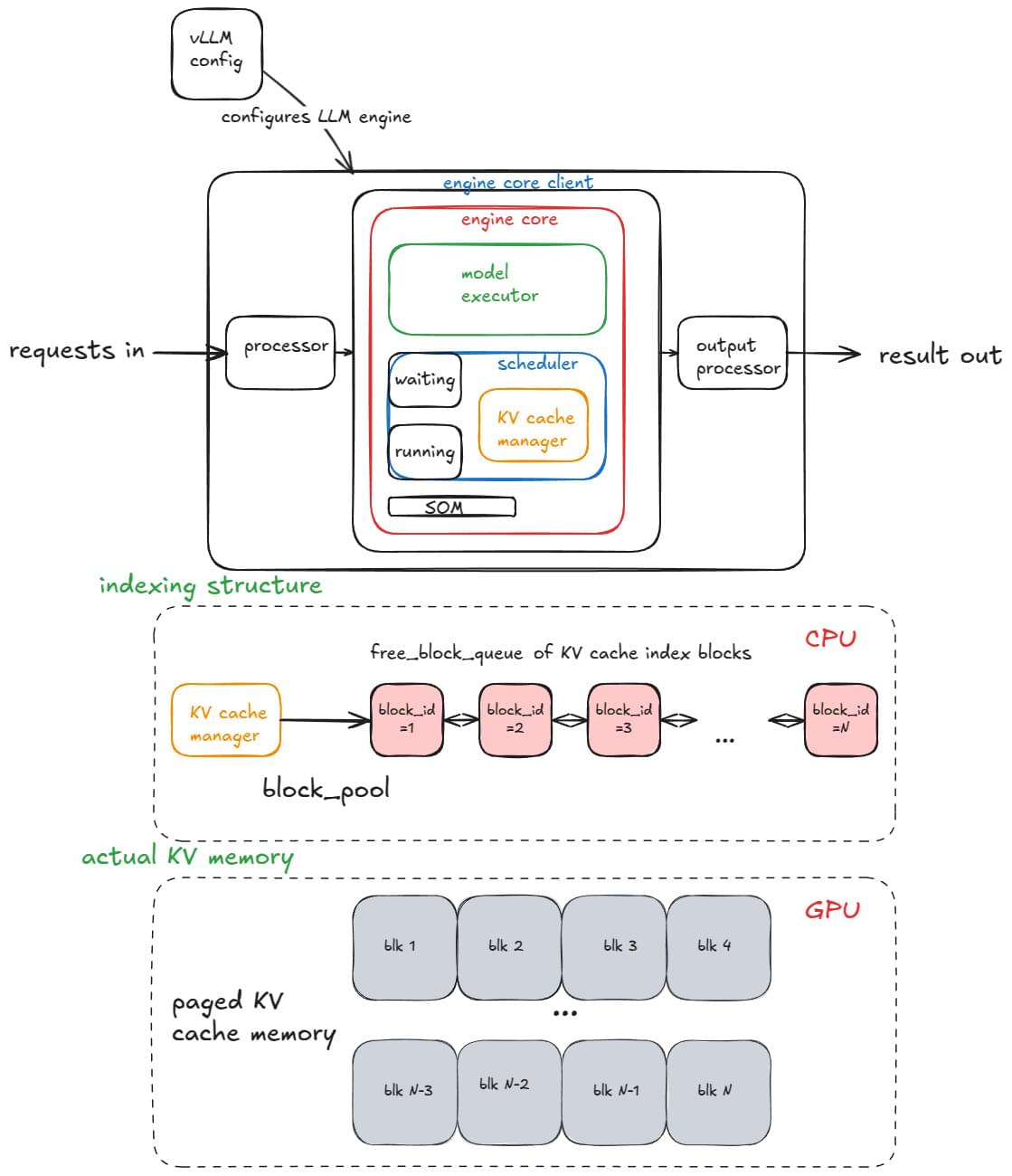

In a major leap for artificial intelligence (AI) and photonics, researchers at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) have created optical generative models capable of producing novel images using the physics of light instead of conventional electronic computation.

Published in Nature, the work presents a new paradigm for generative AI that could dramatically reduce energy use while enabling scalable, high-performance content creation.

Generative models, including diffusion models and large language models, form the backbone of today’s AI revolution. These systems can create realistic images, videos, and human-like text, but their rapid growth comes at a steep cost: escalating power demands, large carbon footprints, and increasingly complex hardware requirements. Running such models requires massive computational infrastructure, raising concerns about their long-term sustainability.

Peter H. Diamandis

Huawei has shocked the electric vehicle (EV) world by filing a patent for a solid-state battery that claims a potential range of 3,000 kilometres and the ability to recharge to full in just five minutes. Normally, we have to assume this particular patent will go nowhere, and we will forget about it; however, it could be the start of something new.

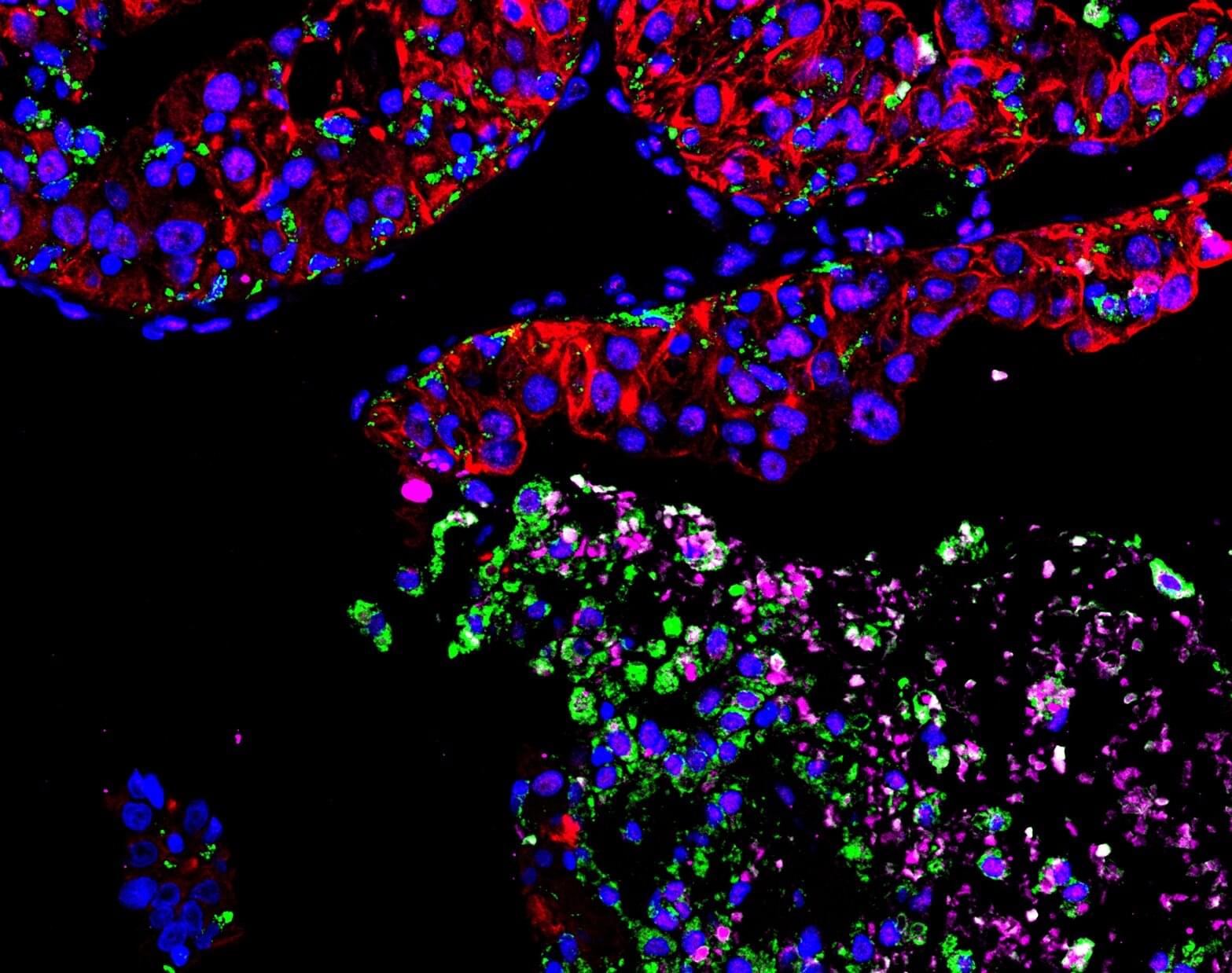

Cancer specialists have long known that anemia, caused by a lack of healthy red blood cells, often arises when cancer metastasizes to the bone, but it’s been unclear why. Now, a research team led by Princeton University researchers Yibin Kang and Yujiao Han has uncovered exactly how this happens in metastatic breast cancer, and it involves a type of cellular hijacking. The research aims to help slow down bone metastasis—one of cancer’s deadliest forms.

In a study published in the journal Cell on September 3, Kang and Han reveal that cancer cells effectively commandeer a specialized cell that normally recycles iron in the bone, known as an erythroblast island (EBI) macrophage. This both deprives red blood cells of necessary iron and helps the tumor continue to grow in the bone.

Understanding metastatic cancer—or cancer that grows and spreads in other parts of the body beyond the original tumor site—is critically important. It is one of the deadliest forms of cancer and there is no cure. Of patients who die from breast and prostate cancer, 70% have bone metastasis.

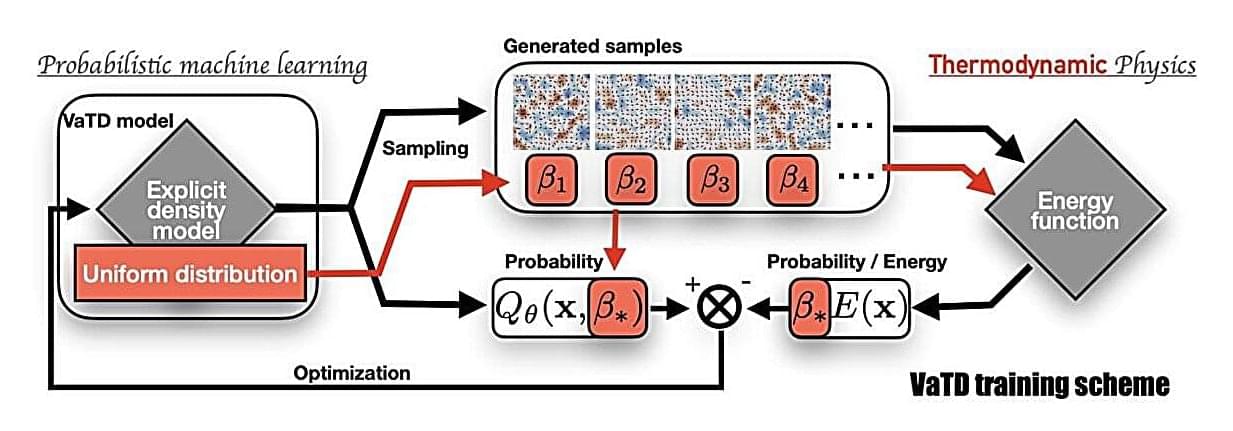

A research team has developed a novel direct sampling method based on deep generative models. Their method enables efficient sampling of the Boltzmann distribution across a continuous temperature range. The findings have been published in Physical Review Letters. The team was led by Prof. Pan Ding, Associate Professor from the Departments of Physics and Chemistry, and Dr. Li Shuo-Hui, Research Assistant Professor from the Department of Physics at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (HKUST).