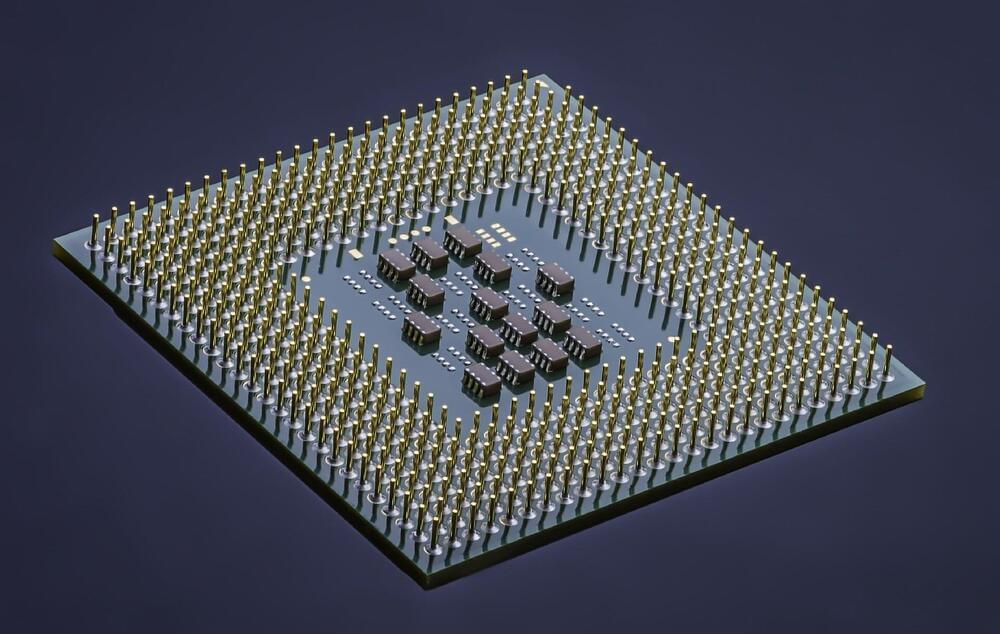

The first molecular electronics chip has been developed, realizing a 50-year-old goal of integrating single molecules into circuits to achieve the ultimate scaling limits of Moore’s Law. Developed by Roswell Biotechnologies and a multi-disciplinary team of leading academic scientists, the chip uses single molecules as universal sensor elements in a circuit to create a programmable biosensor with real-time, single-molecule sensitivity and unlimited scalability in sensor pixel density. This innovation, appearing this week in a peer-reviewed article in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), will power advances in diverse fields that are fundamentally based on observing molecular interactions, including drug discovery, diagnostics, DNA sequencing, and proteomics.

“Biology works by single molecules talking to each other, but our existing measurement methods cannot detect this,” said co-author Jim Tour, Ph.D., a Rice University chemistry professor and a pioneer in the field of molecular electronics. “The sensors demonstrated in this paper for the first time let us listen in on these molecular communications, enabling a new and powerful view of biological information.”

The molecular electronics platform consists of a programmable semiconductor chip with a scalable sensor array architecture. Each array element consists of an electrical current meter that monitors the current flowing through a precision-engineered molecular wire, assembled to span nanoelectrodes that couple it directly into the circuit. The sensor is programmed by attaching the desired probe molecule to the molecular wire, via a central, engineered conjugation site. The observed current provides a direct, real-time electronic readout of molecular interactions of the probe. These picoamp-scale current-versus-time measurements are read out from the sensor array in digital form, at a rate of 1,000 frames per second, to capture molecular interactions data with high resolution, precision and throughput.