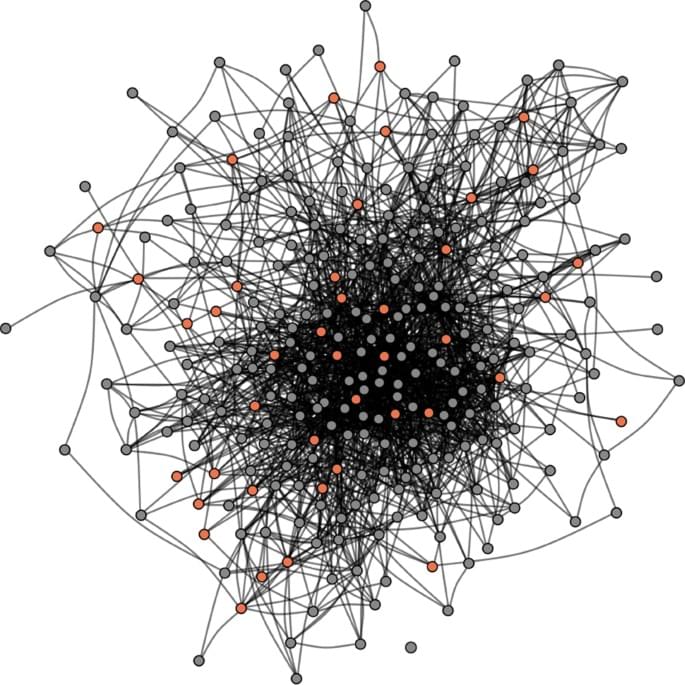

Mathematical models suggest that with just a few more genes, it might be possible to define hundreds of cellular identities, more than enough to populate the tissues of complex organisms. It’s a finding that opens the door to experiments that could bring us closer to understanding how, eons ago, the system that builds us was built.

The Limits of Mutual Repression

Developmental biologists have illuminated many tipping points and chemical signals that prompt cells to follow one developmental pathway or another by studying natural cells. But researchers in the field of synthetic biology often take another approach, explained Michael Elowitz, a professor of biology and bioengineering at Caltech and an author of the new paper: They build a system of cell-fate control from scratch to see what it can tell us about what such systems require.