In a nonrandomized phase 2 trial of adults with advanced dMMR/MSI-H noncolorectal cancers, combined nivolumab/ipilimumab showed an objective response rate of 63% and 6-month progression-free survival rate of 71%.

Main Outcomes and Measures The co-primary end points were objective response rate (ORR) and 6-month progression-free survival (6-PFS) as assessed by Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1, with the secondary end points being median overall survival (mOS), progression-free survival (PFS), and treatment-related toxic effects.

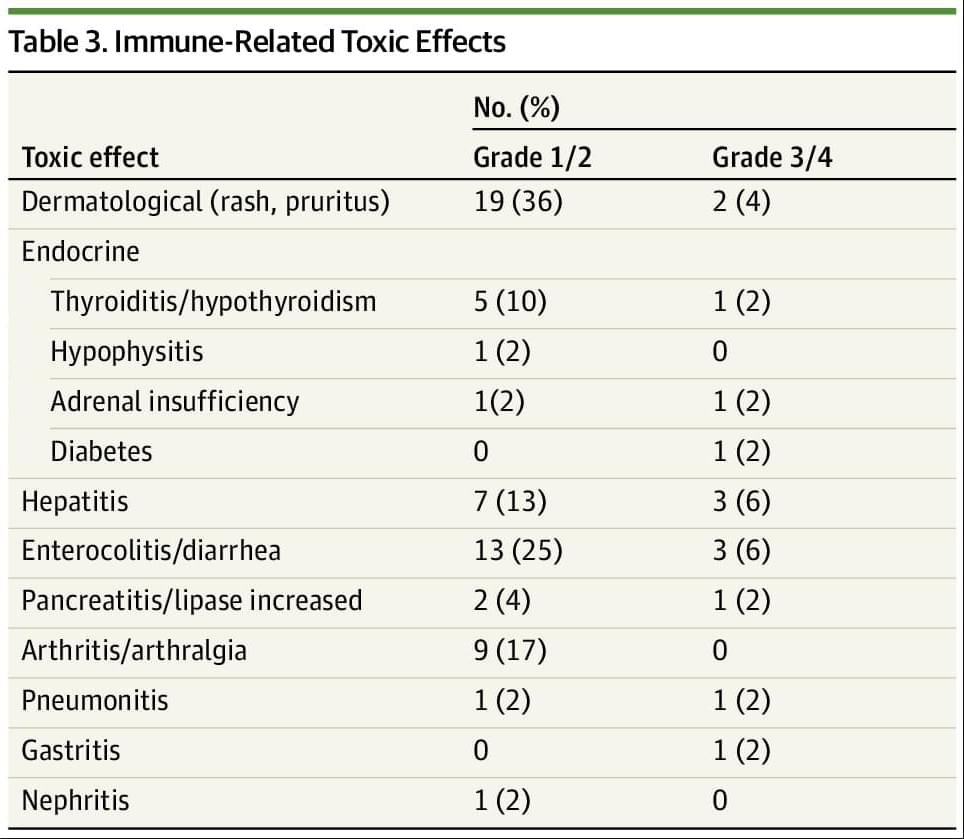

Results Overall, 52 participants were included. The median (range) age of participants was 62 (29−84) years; 41 (79%) were female individuals and 11 (21%) were male individuals. Overall, 52 patients representing 17 tumor types were enrolled, with the most common tumor type being endometrial cancer (26 [50%]). Twenty-seven patients (52%) were pretreated for metastatic disease. ORR was 63% (95% CI, 50% to 75%) with the median duration of response not being reached and 79% of responses being ongoing. The median PFS and OS have not been reached and the 6-month PFS was 71% (95% CI, 57%-81%). Overall, 12 patients (23%) experienced a grade 3/4 immune-related adverse event.

Conclusions and Relevance This nonrandomized clinical trial found that combined anti–PD-1/CTLA-4 blockade was associated with a high rate of durable responses in dMMR/MSI-H noncolorectal cancers, comparing favorably to published trials using anti–PD-1/programmed cell death ligand 1 monotherapy. Anti–PD-1/CTLA-4 blockade using nivolumab and ipilimumab may represent an alternative treatment option to monotherapy in this patient population.