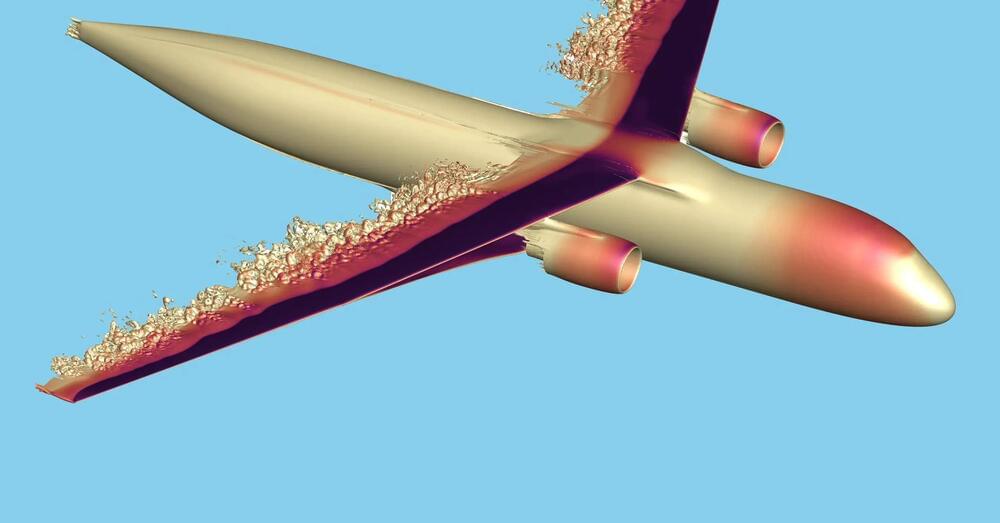

No, it’s not hypermodern art. This image, generated by NASA

Established in 1958, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) is an independent agency of the United States Federal Government that succeeded the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA). It is responsible for the civilian space program, as well as aeronautics and aerospace research. Its vision is “To discover and expand knowledge for the benefit of humanity.” Its core values are “safety, integrity, teamwork, excellence, and inclusion.” NASA conducts research, develops technology and launches missions to explore and study Earth, the solar system, and the universe beyond. It also works to advance the state of knowledge in a wide range of scientific fields, including Earth and space science, planetary science, astrophysics, and heliophysics, and it collaborates with private companies and international partners to achieve its goals.