EIN Presswire is a press release distribution service of EIN News.

Sponsored by Blinkist: Use our special link to start your free 7-day trial with Blinkist and get 25% off of a premium membership: https://www.blinkist.com/beeyondideas.

In this video, we’ll sit down in our time machine and go forward a few millenniums into the future, to see where we would be progressing as a civilization.

Chapters:

0:00 Opening.

0:51 The levels of civilization.

2:13 Timelapse of the future.

5:25 Year 2141

6:34 Year 2768

8:43 Conclusion.

If you’d like to see more of this kind of video, consider supporting our work by becoming a member today!

https://www.youtube.com/BeeyondIdeas/join.

Follow us on Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/beeyond.ideas/

Music tracks in this video:

Since the isolation of graphene, we’ve identified a number of materials that form atomically thin sheets. Like graphene, some of these sheets are made of a single element; others form from chemicals where the atomic bonds naturally create a sheet-like structure. Many of these materials have distinct properties. While graphene is an excellent conductor of electricity, a number of others are semiconductors. And it’s possible to tune their properties further based on how you arrange the layers of a multi-sheet stack.

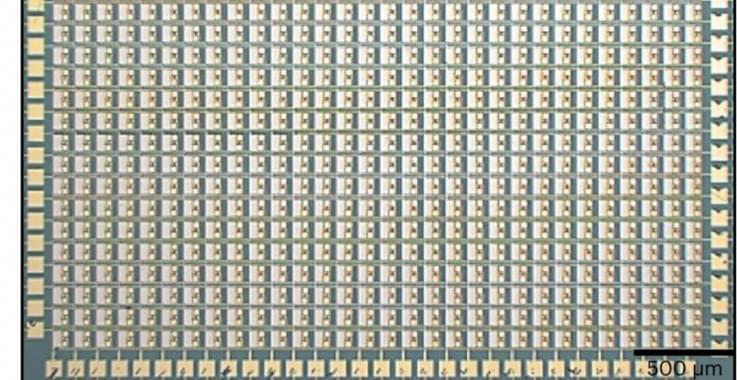

Given all those options, it shouldn’t surprise anyone that researchers have figured out how to make electronics out of these materials, including flash memory and the smallest transistors ever made, by some measures. Most of these, however, are demonstrations of the ability to make the hardware—they’re not integrated into a useful device. But a team of researchers has now demonstrated that it’s possible to go beyond simple demonstrations by building a 900-pixel imaging sensor using an atomically thin material.

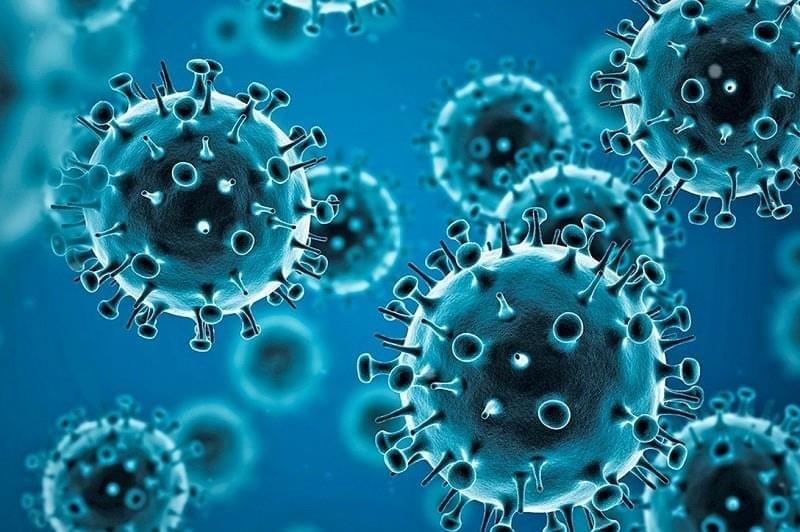

As part of its ongoing work to track variants, WHO’s Technical Advisory Group on SARS-CoV-2 Virus Evolution (TAG-VE) met on the 24 October 2022 to discuss the latest evidence on the Omicron variant of concern, and how its evolution is currently unfolding, in light of high levels of population immunity in many settings and country differences in the immune landscape. In particular, the public health implications of the rise of some Omicron variants, specifically XBB and its sublineages (indicated as XBB•, as well as BQ.1 and its sublineages (indicated as BQ.1•, were discussed. Based on currently available evidence, the TAG-VE does not feel that the overall phenotype of XBB* and BQ.1* diverge sufficiently from each other, or from other Omicron lineages with additional immune escape mutations, in terms of the necessary public health response, to warrant the designation of new variants of concern and assignment of a new label. The two sublineages remain part of Omicron, which continues to be a variant of concern. This decision will be reassessed regularly. If there is any significant development that warrant a change in public health strategy, WHO will promptly alert Member States and the public. XBB*XBB* is a recombinant of BA.2.10.1 and BA.2.75 sublineages. As of epidemiological week 40 (3 to 9 October), from the sequences submitted to GISAID, XBB* has a global prevalence of 1.3% and it has been detected in 35 countries. The TAG-VE discussed the available data on the growth advantage of this sublineage, and some early evidence on clinical severity and reinfection risk from Singapore and India, as well as inputs from other countries. There has been a broad increase in prevalence of XBB* in regional genomic surveillance, but it has not yet been consistently associated with an increase in new infections. While further studies are needed, the current data do not suggest there are substantial differences in disease severity for XBB* infections. There is, however, early evidence pointing at a higher reinfection risk, as compared to other circulating Omicron sublineages. Cases of reinfection were primarily limited to those with initial infection in the pre-Omicron period. As of now, there are no data to support escape from recent immune responses induced by other Omicron lineages. Whether the increased immune escape of XBB* is sufficient to drive new infection waves appears to depend on the regional immune landscape as affected by the size and timing of previous Omicron waves, as well as the COVID-19 vaccination coverage. BQ.1*BQ.1* is a sublineage of BA.5, which carries spike mutations in some key antigenic sites, including K444T and N460K. In addition to these mutations, the sublineage BQ.1.1 carries an additional spike mutation in a key antigenic site (i.e. R346T). As of epidemiological week 40 (3 to 9 October), from the sequences submitted to GISAID, BQ.1* has a prevalence of 6% and it has been detected in 65 countries. While there are no data on severity or immune escape from studies in humans, BQ.1* is showing a significant growth advantage over other circulating Omicron sublineages in many settings, including Europe and the US, and therefore warrants close monitoring. It is likely that these additional mutations have conferred an immune escape advantage over other circulating Omicron sublineages, and therefore a higher reinfection risk is a possibility that needs further investigation. At this time there is no epidemiologic data to suggest an increase in disease severity. The impact of the observed immunological changes on vaccine escape remains to be established. Based on currently available knowledge, protection by vaccines (both the index and the recently introduced bivalent vaccines) against infection may be reduced but no major impact on protection against severe disease is foreseen. Overall summaryThe Omicron variant of concern remains the dominant variant circulating globally, accounting for nearly all sequences reported to GISAID[1]. While we are looking at a vast genetic diversity of Omicron sublineages, they currently display similar clinical outcomes, but with differences in immune escape potential. The potential impact of these variants is strongly influenced by the regional immune landscape. While reinfections have become an increasingly higher proportion of all infections, this is primarily seen in the background of non-Omicron primary infections. With waning immune response from initial waves of Omicron infection, and further evolution of Omicron variants, it is likely that reinfections may rise further. The role of the TAG-VE is to alert WHO if a variant with a substantially different phenotype (e.g. a variant that can cause a more severe disease or lead to large epidemic waves causing increased burden to the healthcare system) is emerging and likely to pose a significant threat. Based on currently available evidence, the TAG-VE does not feel that the overall phenotype of XBB* and BQ.1* diverge sufficiently from each other, or from other Omicron sublineages with additional immune escape mutations, in terms of the necessary public health response, to warrant the designation of a new variant of concern and assignment of a new label, but the situation will be reassessed regularly. We note these two sublineages remain part of Omicron, which is a variant of concern with very high reinfection and vaccination breakthrough potential, and surges in new infections should be handled accordingly. While so far there is no epidemiological evidence that these sublineages will be of substantially greater risk compared to other Omicron sublineages, we note that this assessment is based on data from sentinel nations and may not be fully generalizable to other settings. Wide-ranging, systematic laboratory-based efforts are urgently needed to make such determinations rapidly and with global interpretability. WHO will continue to closely monitor the XBB* and BQ.1* lineages as part of Omicron and requests countries to continue to be vigilant, to monitor and report sequences, as well as to conduct independent and comparative analyses of the different Omicron sublineages. The TAG-VE meets regularly and continues to assess the available data on the transmissibility, clinical severity, and immune escape potential of variants, including the potential impact on diagnostics, therapeutics, and the effectiveness of vaccines in preventing infection and/or severe disease. [1] Weekly epidemiological update on COVID-19 — 26 October 2022 (who.int)

According to an article by the university, the study is significant because it is a sign of future viability for noninvasive technology to help those with limited motor function.

“We demonstrated that the people who will actually be the end users of these types of devices are able to navigate in a natural environment with the assistance of a brain-machine interface,” said José del R. Millán, professor at the Cockrell School of Engineering’s Chandra Family Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering and leader of the international research team.

Circa 2013 face_with_colon_three

“IMAGINE printing out a paper computer and tearing off a corner so someone else can use part of it.” So says Steve Hodges of Microsoft Research in Cambridge, UK. The idea sounds fantastical, but it could become an everyday event thanks in part to a technique he helped develop.

Hodges, along with Yoshihiro Kawahara and his team at the University of Tokyo, Japan, have found a way to print the fine, silvery lines of electronic circuit boards onto paper. What’s more, they can do it using ordinary inkjet printers, loaded with ink containing silver nanoparticles. Last month Kawahara demonstrated a paper-based moisture sensor at the Ubicomp conference in Zurich, Switzerland.

Kawahara says the idea is perfect for the growing maker movement of inventors and tinkerers. Hobbyists will be able to test circuit designs by simply printing them out and throwing away anything that doesn’t work. That will reduce much of electronics to a craft akin to “sewing or origami”, he says.

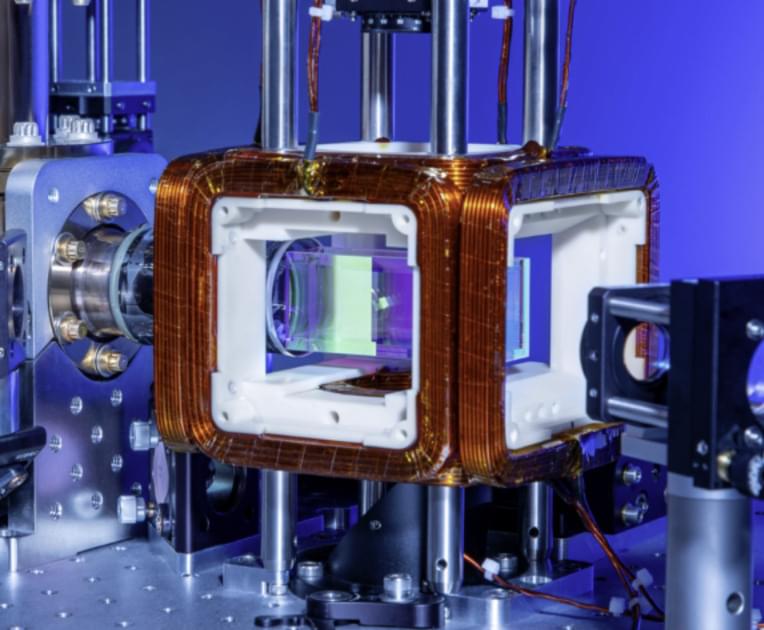

Quantum researchers require access to different types of quantum hardware from digital, also known as gate-based, quantum processing units (QPUs) to analog devices that are capable of addressing specific problems that are hard to solve using classical computers. Today, Amazon Braket, the quantum computing service from AWS, continues to deliver on its commitment to provide that choice by launching Aquila, pictured in Figure 1 below, a new neutral-atom QPU from QuEra Computing with up to 256 qubits. As a special purpose device designed for solving optimization problems and simulating quantum phenomena in nature, it enables researchers to explore a new analog paradigm of quantum computing.

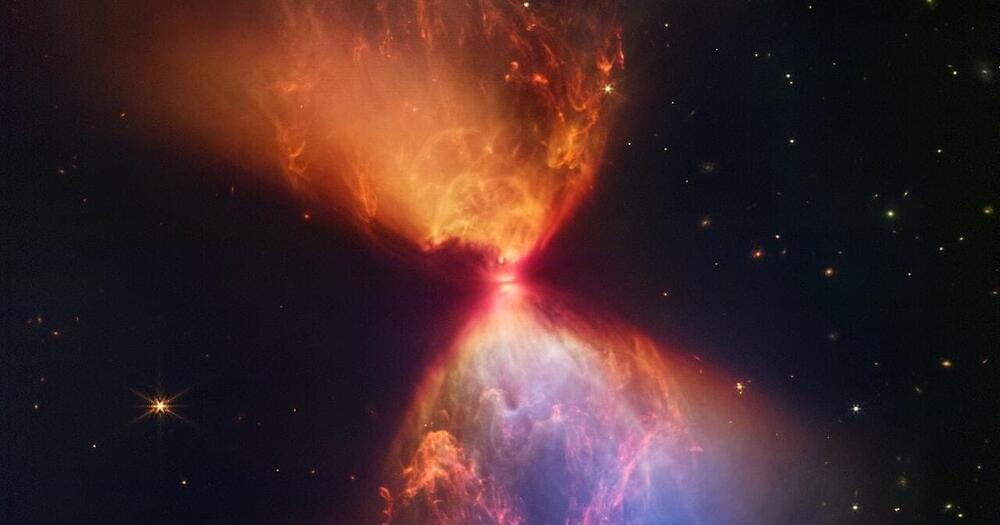

Webb’s NIRCam instrument recently captured this detailed image of the cloudy region around a very young protostar called L1527. Only about 100,000 years old, L1527 isn’t a star yet: it hasn’t fully pulled itself into a proper, stable sphere, and it hasn’t piled on enough mass to kickstart nuclear fusion and start pumping out its own energy. It’s more like “a small, hot, and puffy clump of gas, somewhere between 20 percent and 40 percent the mass of our Sun,” according to the European Space Agency.

But as the latest Webb photos reveal, the young protostar is making an ambitious start.

The new alternative positioning system could achieve an accuracy of 10 centimeters.

Researchers have created an alternative positioning system that is more accurate and robust than GPS. The team discovered that the alternative positioning system is more accurate within urban settings. The prototype that demonstrated this new mobile network infrastructure was able to achieve an accuracy of 10 centimeters.

The results from the study were published in the journal Nature. University of Technology/tudelft.nl.

It has been built to be a self-sustaining floating city.

Designer Pierpaolo Lazzarini has proposed a concept for a bold and innovative terayacht which is a giant floating continent double the size of the Roman Colosseum, as first reported by DesignBoom last Friday. It’s called the Pangeos watercraft and it consists of a floating city that includes various hotels, shopping centers, parks, as well as ship and aircraft ports.

Inspired by Pangea.

The concept can host up to 60,000 guests in the middle of the sea surrounded by water and is in the shape of a gigantic turtle.

Lazzarini Design Studio.