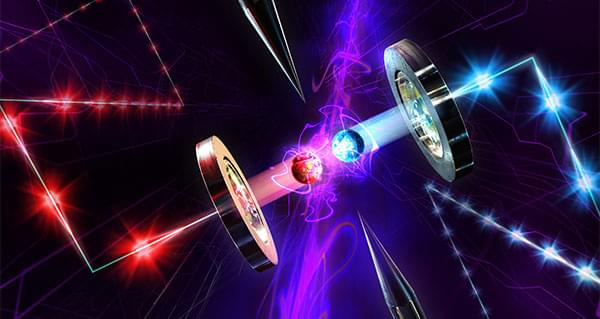

Device uses two trapped ions to raise the performance of a 50-km-long entangled fiber link.

The material can self-heal in just 24 hours when warmed to 158°F or in about a week at room temperature.

Stanford professor Zhenan Bao and his team have invented a multi-layer self-healing synthetic electronic skin.

This is according to a report by Fox News published on Friday.

Stanford scientists have invented a multi-layer self-healing synthetic electronic skin that can now self-recognize and align with each other when injured, allowing the skin to continue functioning while healing.

It’s ideal for search and rescue missions.

Scientists at the ETH Zurich spinoff company Tethys Robotics have developed an underwater robot that can be deployed in situations that are too dangerous for human divers to undertake.

This is according to a report by InceptiveMind published on Saturday.

The new machine is an autonomous underwater vehicle that has been specifically engineered for use in challenging and dangerous environments like turbid channels and rivers. When conventional search and rescue techniques fail, the Tethys robot is there to take over.

Machine learning has an “AI” problem. With new breathtaking capabilities from generative AI released every several months — and AI hype escalating at an even higher rate — it’s high time we differentiate most of today’s practical ML projects from those research advances. This begins by correctly naming such projects: Call them “ML,” not “AI.” Including all ML initiatives under the “AI” umbrella oversells and misleads, contributing to a high failure rate for ML business deployments. For most ML projects, the term “AI” goes entirely too far — it alludes to human-level capabilities. In fact, when you unpack the meaning of “AI,” you discover just how overblown a buzzword it is: If it doesn’t mean artificial general intelligence, a grandiose goal for technology, then it just doesn’t mean anything at all.

Page-utils class= article-utils—vertical hide-for-print data-js-target= page-utils data-id= tag: blogs.harvardbusiness.org, 2007/03/31:999.357346 data-title= The AI Hype Cycle Is Distracting Companies data-url=/2023/06/the-ai-hype-cycle-is-distracting-companies data-topic= AI and machine learning data-authors= Eric Siegel data-content-type= Digital Article data-content-image=/resources/images/article_assets/2023/06/Jun23_02_Skizzomat-383x215.jpg data-summary=

By focusing on sci-fi goals, they’re missing out on projects that create real value right now.

Researchers have trained a robotic ‘chef’ to watch and learn from cooking videos, and recreate the dish itself.

The researchers, from the University of Cambridge, programmed their robotic chef with a cookbook of eight simple salad recipes. After watching a video of a human demonstrating one of the recipes, the robot was able to identify which recipe was being prepared and make it.

In addition, the videos helped the robot incrementally add to its cookbook. At the end of the experiment, the robot came up with a ninth recipe on its own. Their results, reported in the journal IEEE Access, demonstrate how video content can be a valuable and rich source of data for automated food production, and could enable easier and cheaper deployment of robot chefs.

According to 81% of hospital CIOs surveyed by my company, security vulnerability is the leading pain point driving legacy data management decisions. That’s no surprise as healthcare continues to rank as one of the most cyber-attacked industries year over year. In a study by the Health Information and Management Systems Society (HIMSS), 80% of healthcare organizations reported having legacy operating systems in place. Cybersecurity in healthcare is increasingly becoming a chronic condition.

The Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), which measures risk to critical national infrastructure, says legacy software ranks as a dangerous “bad practice.” That’s because the use of unsupported or end-of-life legacy systems offers some of the easiest entry points for bad actors to gain access and cause havoc within a medical environment. With the average price tag for a healthcare data breach at an all-time high of $10.1 million, the overall cost to a breached organization is high in terms of economic loss and reputation repair.

To fortify defenses against cyberattacks, here are some tips for addressing out-of-production software in healthcare facilities.

In a recent study published in Nature Medicine, researchers conducted a genome-wide analysis of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels of men without prostate cancer to understand the non-cancer-related variation in PSA levels to improve decision-making during the diagnosis of prostate cancer.

Study: Genetically adjusted PSA levels for prostate cancer screening. Image Credit: luchschenF/Shutterstock.com.