Year 2022 😗😁

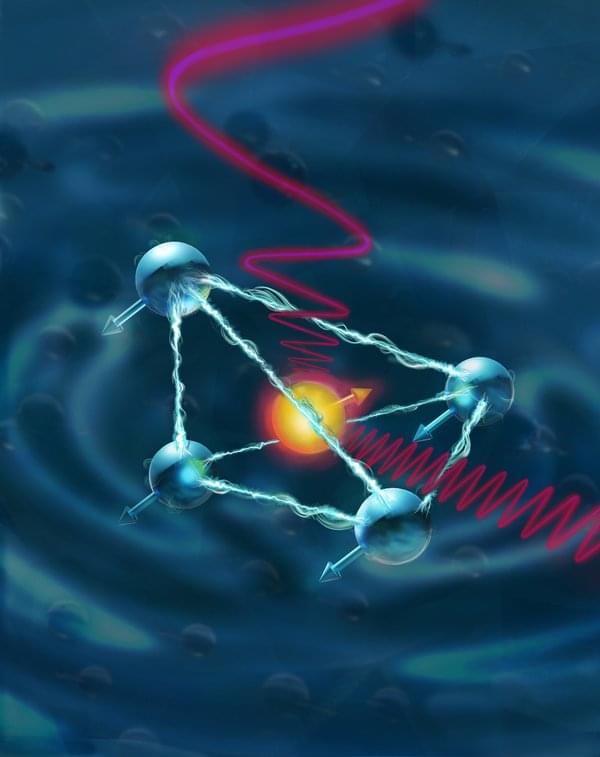

Data stored in spin states of ytterbium atoms can be transferred to surrounding atoms in a crystal matrix.

A study led by researchers at Sanford Burnham Prebys has found that in young women, certain genetic mutations are associated with treatment-resistant breast cancer. These mutations are not linked to treatment-resistant breast cancer in older women. The findings, published in the journal Science Advances, could help improve precision medicine and suggest a brand-new way of classifying breast cancer.

“It’s well established that as you get older, you’re more likely to develop cancer. But we’re finding that this may not be true for all cancers depending on a person’s genetic makeup,” says senior author Svasti Haricharan, Ph.D., an assistant professor at Sanford Burnham Prebys. “There may be completely different mechanisms driving cancer in younger and older people, which requires adjusting our view of aging and cancer.”

The research primarily focused on ER+/HER2-breast cancer, which is one of the most common forms of the disease. It is usually treated with hormonal therapies, but for some patients, these treatments don’t work. About 20% of tumors resist treatment from the very beginning, and up to 40% develop resistance over time.

Facebook’s AI guru and machine learning pioneer Yann Lecun is coming for the artificial intelligence chatbot craze — and it may put him at odds with his own employer.

As Fortune reports, Meta’s chief AI scientist Yann Lecun admitted during a talk in Paris this week that he’s not exactly a fan of the current spate of chatbots and the large language models (LLMs) they’re built on.

“A lot of people are imagining all kinds of catastrophe scenarios because of AI, and it’s because they have in mind these auto-regressive LLMs that kind of spew nonsense sometimes,” he told the Meta Innovation Press Day crowd. “They say it’s not safe. They are right. It’s not. But it’s also not the future.”

One tip that I always give to family members, friends, and passersby when asked, “How can I make my phone faster?” is straightforward yet typically hidden, and that’s adjusting the animation speed. The method of doing so is quick, simple, and absolutely free. And as a bonus, you’ll feel like the “guy behind the computer” from every action movie. Just follow the steps below.

A few taps and a swipe are all it takes to make your Android phone feel like new again.

MEET FLIPPY. STARTING in 2021, this tireless fry-station specialist toiled in 10 Chicago-area locations of White Castle, America’s first fast-food hamburger chain. Working behind a protective shield to reduce burn risk, Flippy could automatically fill and empty frying baskets as well as identify foods for frying and place them in the correct basket. While Flippy safely cooked French fries, White Castle employees could focus on serving customers and performing other restaurant tasks. That’s because Flippy is an AI-powered robot.

According to the International Federation of Robotics, more than half a million industrial robots are installed around the world, most in manufacturing. Now, a shortage of qualified workers is pushing more companies to explore using robots in a wide range of roles, from filling online orders in warehouses to making room service deliveries in hotels.

The restaurant industry is using AI to improve the human side of hospitality.

This car is interesting, and approved and certified by the FAA.

Alef Aeronautics unveiled a prototype of its first Alef flying car on Wednesday, a $300,000 machine the company hopes will let well-heeled commuters both drive on roads and soar over traffic starting in 2025.

Never miss a deal again! See CNET’s browser extension 👉 https://bit.ly/39Ub3bv.

In the next two decades, human beings will return to the moon, set foot on Mars, and launch telescopes capable of detecting extraterrestrial life. NASA’s outgoing head scientist Thomas Zurbuchen oversaw much of the planning for these projects, and space agencies around the world are pursuing similar goals collaboratively. Brian Greene is joined by Zurbuchen, Japan’s Masaki Fujimoto, Europe’s Kirsten MacDonnell and Australia’s Aude Vignelles, as they reveal their plans for what promises to be a New Golden Age of Space Exploration.

This program is part of the Big Ideas series, supported by the John Templeton Foundation.

The live program was presented at the 2023 World Science Festival Brisbane, hosted by the Queensland Museum.

Participants:

Masaki Fujimoto.

Kirsten MacDonell.

Aude Vignelles.

Thomas Zurbuchen.

Moderator:

Brian Greene.

SHARE YOUR THOUGHTS on this program through a short survey:

When markets closed Friday, Apple’s market capitalization was more than $3 trillion, making it the most valuable company — ever.

It’s a massive milestone for the tech giant, which warned investors in May that its current-quarter revenue was expected to decline. But Friday’s stock price increasing by just over 2 percent to close at $193.97 per share suggests that investors are still confident in the company, a bright spot in an industry that has otherwise been rocked by layoffs and uncertainty over the past year.

Apple hits $3 million market cap for the first time Friday, suggesting that investors are still confident in the company.

Flexible displays that can change color, convey information and even send veiled messages via infrared radiation are now possible, thanks to new research from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Engineers inspired by the morphing skins of animals like chameleons and octopuses have developed capillary-controlled robotic flapping fins to create switchable optical and infrared light multipixel displays that are 1,000 times more energy efficient than light-emitting devices.

The new study led by mechanical science and engineering professor Sameh Tawfick demonstrates how bendable fins and fluids can simultaneously switch between straight or bent and hot and cold by controlling the volume and temperature of tiny fluid-filled pixels. Varying the volume of fluids within the pixels can change the directions in which the flaps flip—similar to old-fashioned flip clocks—and varying the temperature allows the pixels to communicate via infrared energy. The study findings are published in the journal Science Advances.

Tawfick’s interest in the interaction of elastic and capillary forces—or elasto-capillarity—started as a graduate student, spanned the basic science of hair wetting and led to his research in soft robotic displays at Illinois.

Summary: A ‘smart hand exoskeleton’, a custom-made robotic glove, can aid stroke patients in relearning dexterity-based skills like playing music. The glove, equipped with integrated tactile sensors, soft actuators, and artificial intelligence, can mimic natural hand movements and provide tactile sensations.

By applying machine learning, the glove can distinguish between correct and incorrect piano play, potentially offering a novel tool for personalized rehabilitation. Although the current design focuses on music, the technology holds promise for a broader range of rehabilitation tasks.