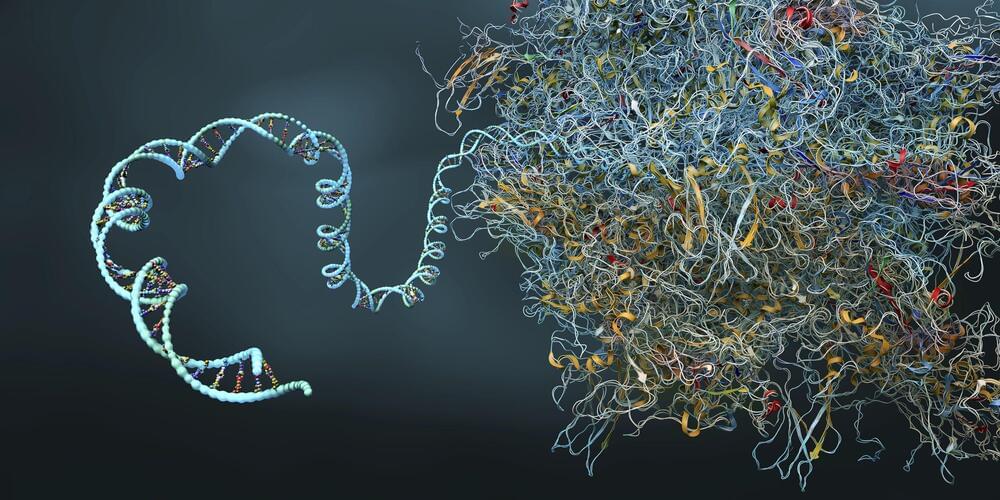

One of the oldest known molecules, the ribosome, creates proteins based on a copy of the genetic code found in the genome, known as mRNA. Scientists have believed that the ribosome performed the same type of work with all mRNA, like a standardized assembly line that it did not regulate on its own. However, researchers from the University of Copenhagen have discovered this is not the case.

Their findings are published in the journal Developmental Cell in an article entitled “Ribosomal RNA 2′-O-methylation dynamics impact cell fate decisions.”

“It has long been known that there are different types of ribosomes. But it has been assumed that no matter what mRNA you give the ribosome, it will produce a protein. But our results suggest that different types of ribosomes produce specific proteins,” says Anders H. Lund, professor at the Biotech Research and Innovation Center at the University of Copenhagen.