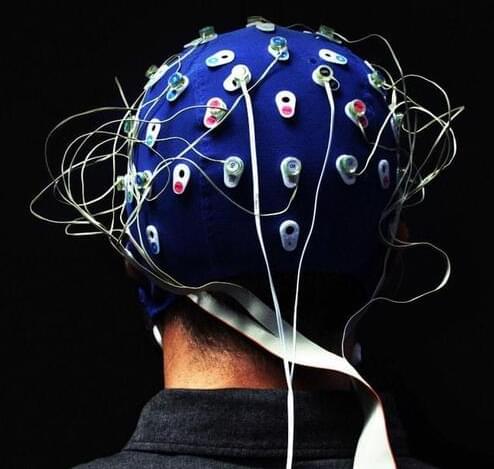

EPFL researchers have shown that people’s perception of office temperature can vary considerably. Personalized climate control could therefore help enhance workers’ comfort—and save energy at the same time.

Global warming means that heatwaves are becoming ever-more frequent. At the same time, we’re in a global race against the clock to reduce buildings’ energy use and carbon footprint by 2050. This has shone the spotlight on the importance of making the thermal comfort of buildings a strategic and economic priority. And this is the focus of research conducted by Dolaana Khovalyg, a tenure track assistant professor at EPFL’s School of Architecture, Civil and Environmental Engineering (ENAC) and head of the Laboratory of Integrated Comfort Engineering (ICE), which is linked to the Smart Living Lab in Fribourg.

In her latest study, published as a brief, cutting-edge report in the journal Obesity, she highlights the benefits of providing personalized thermal conditioning and heating for each office desk, rather than maintaining a standard temperature throughout an open space. Khovalyg and her team came to this conclusion after the human thermo-physiological data they collected showed that individuals display very different levels of thermal comfort under normal office conditions.