Researchers found a fake Ethereum helper package on crates.io that secretly downloaded OS-specific payloads and executed them on developer machines.

Microsoft fixes the Windows LNK flaw CVE-2025–9491, a bug exploited by multiple state groups since 2017.

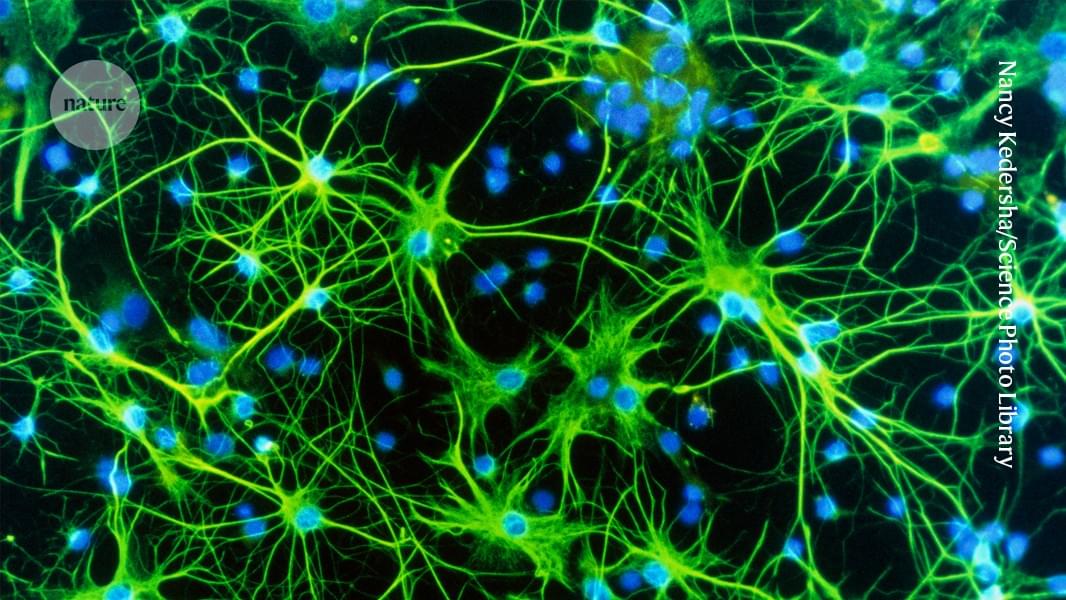

Researchers peered through microscopes, hooked up electrodes, and built entire careers around one cell type: neurons. These electrically active cells were clearly the brain’s protagonists, zipping signals through our heads at lightning speed to create thoughts, memories, and movements. Everything else—especially the star-shaped cells called astrocytes that outnumber neurons—was dismissed as mere scaffolding. Glial cells, they were called: “glue.”

Inbal Goshen, a memory researcher at Hebrew University of Jerusalem, remembers feeling like an outsider when she started investigating astrocytes in the early 2010s. “Oh, that’s the weird one who works on astrocytes,” she imagined colleagues whispering at conferences. The skepticism was palpable. Yet new molecular tools had finally given her a way to peek into these mysterious cells, and what she found was too intriguing to ignore.

Unlike neurons, astrocytes don’t fire electrical signals. They were “electrically silent,” which is why they’d been ignored. But they were whispering in another language entirely: calcium. Using advanced imaging, researchers discovered that astrocytes communicate through slow, rhythmic waves of calcium signals—more like a gentle tide than neuron’s lightning strike. And their reach is astonishing: a single human astrocyte can touch up to two million synapses, the junctions where neurons meet. Their bushy tendrils fill every crevice of the brain, each cell nestling against neurons and blood vessels, creating an intimate, three-way relationship.

Memory research revealed another layer. Goshen’s team watched astrocytes in mice navigating toward water rewards. As the animals approached familiar prize locations, astrocyte activity slowly ramped up—but showed no response in new environments. The cells were encoding spatial memories, not just supporting them. Other labs found that astrocytes help stabilize and recall fear memories, their slow calcium signals perfectly suited to bridge the gap between learning something and remembering it days later. As neuroscientist Jun Nagai describes it, “Think of them as the brain’s long-exposure camera: they capture the trace of meaningful events that might otherwise fade too fast.”

Astrocytes make up one-quarter of the brain, but researchers are only now realizing their true value.

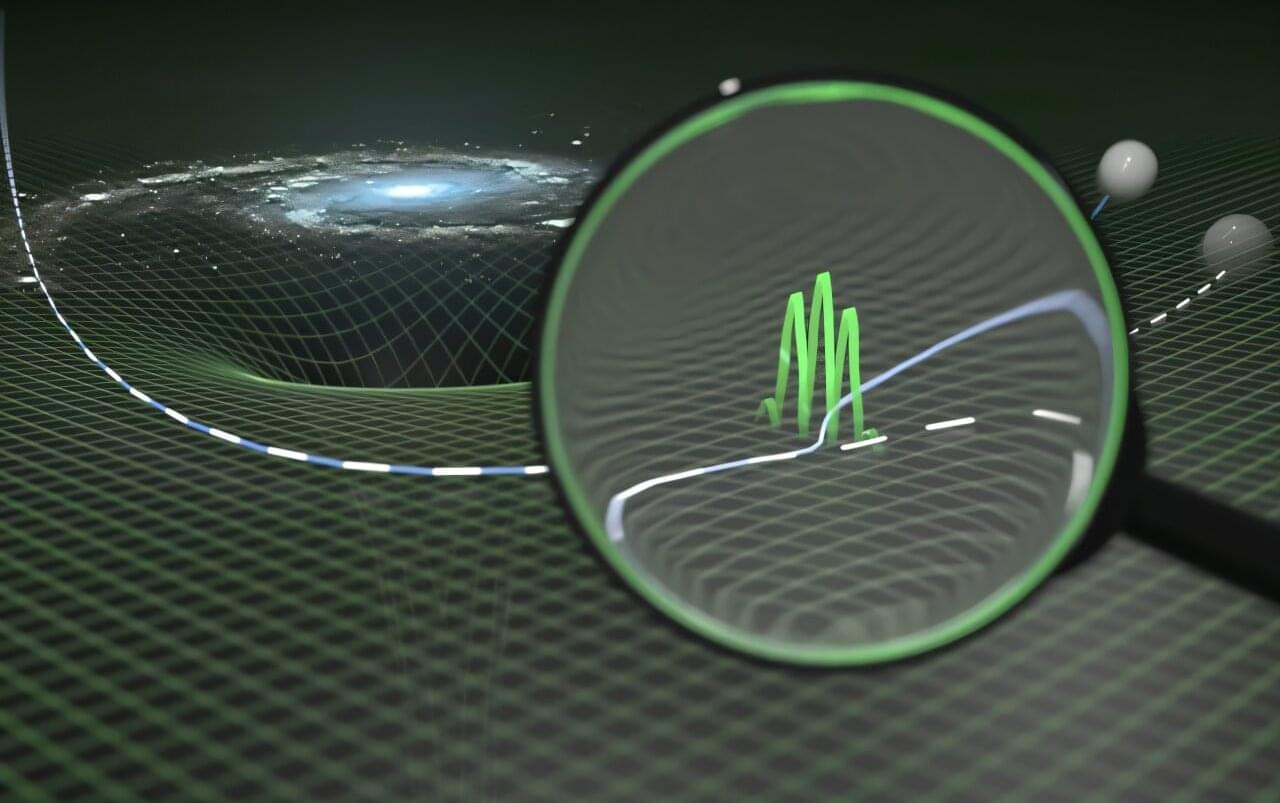

It is something like the “Holy Grail” of physics: unifying particle physics and gravitation. The world of tiny particles is described extremely well by quantum theory, while the world of gravitation is captured by Einstein’s general theory of relativity. But combining the two has not yet worked—the two leading theories of theoretical physics still do not quite fit together.

There are many ideas for such a unification—with names like string theory, loop quantum gravity, canonical quantum gravity or asymptotically safe gravity. Each of them has its strengths and weaknesses. What has been missing so far, however, are observable predictions for measurable quantities and experimental data that could reveal which of these theories actually describes nature best. A new study from TU Wien published in Physical Review D may now have brought us a small step closer to this ambitious goal.