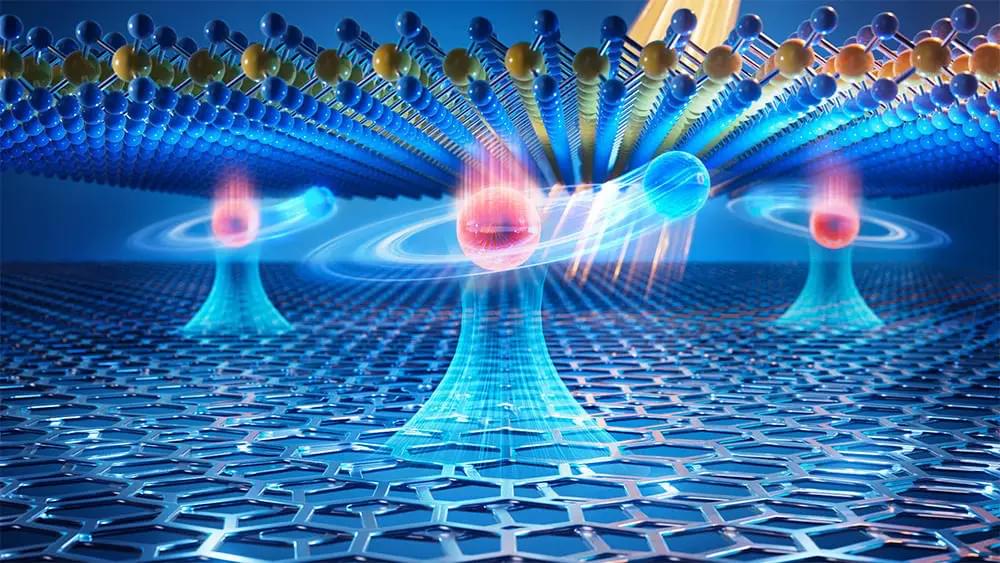

Perovskite-based light emitting diodes (LEDs) could be the key to developing internet bandwidths orders of magnitude faster than what is now available, while also keeping energy consumption and cost down, researchers have claimed. Other potential applications lie in laser technology.

Perovskite is a natural mineral first identified in Russia’s Ural Mountains in 1,839 and composed primarily of calcium, titanium, and oxygen – all in the 10 most common elements in the Earth’s crust. The mineral gave its name to a class of materials based on the same elements but doped with small quantities of others. For almost the first two centuries after their discovery, these perovskites were largely a curiosity of interest only to chemists.

More recently, however, the ability of perovskites to display different electrical properties depending on the atoms with which they are doped has turned them into a wonder material. Perovskites now represent one of the most efficient ways to trap energy from sunlight and are continuing to improve at unprecedented rates. Moreover, perovskites have the potential to be manufactured far more cheaply than traditional silicon-based solar cells, while a layer of perovskite over a silicon base could capture more light than either on their own.