Physicists at the National Ignition Facility are learning how to better control crushingly violent “shots”.

In a new video, Intel has demoed the video playback capability of its Meteor Lake iGPU and its Low-Power E-Cores.

Intel Meteor Lake iGPU Offers Smooth 8K60 Video Playback, 1080P Video Playback Also Possible On SOC Tile’s Low-Power E-Cores

The Intel Meteor Lake, 1st Gen Core Ultra, CPUs are composed of various IPs and architectures. The tiled architecture incorporates a range of technologies and Intel is showcasing the advantages that it brings with its next-gen CPU architectures. For this purpose, Intel demoed video playback on the Meteor Lake iGPU and its low-power E-Cores and the results are super interesting.

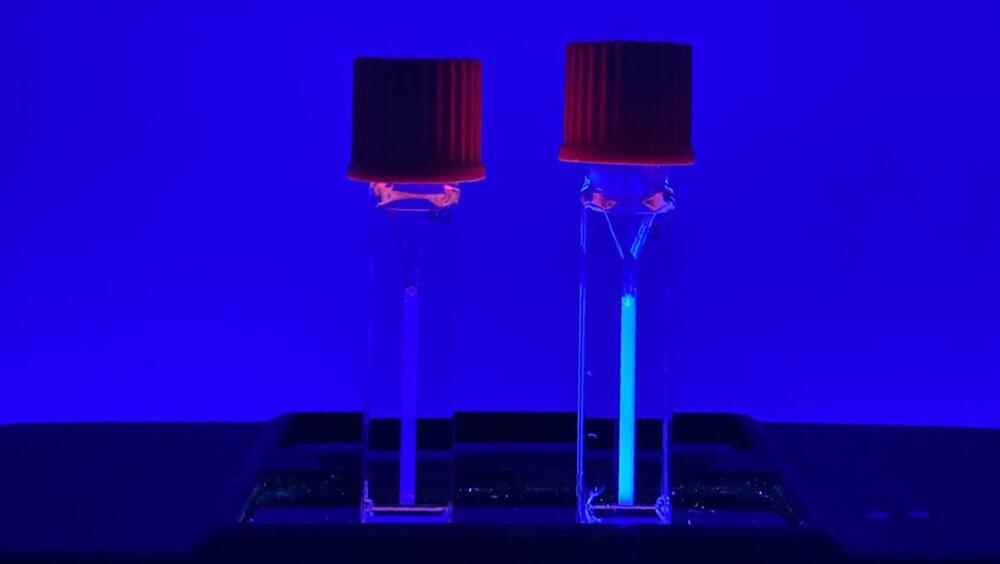

Remote control of chemical reactions in biological environments could enable a diverse range of medical applications. The ability to release chemotherapy drugs on target in the body, for example, could help bypass the damaging side effects associated with these toxic compounds. With this aim, researchers at California Institute of Technology (Caltech) have created an entirely new drug-delivery system that uses ultrasound to release diagnostic or therapeutic compounds precisely when and where they are needed.

The platform, developed in the labs of Maxwell Robb and Mikhail Shapiro, is based around force-sensitive molecules known as mechanophores that undergo chemical changes when subjected to physical force and release smaller cargo molecules. The mechanical stimulus can be provided via focused ultrasound (FUS), which penetrates deep into biological tissues and can be applied with submillimetre precision. Earlier studies on this method, however, required high acoustic intensities that cause heating and could damage nearby tissue.

To enable the use of lower – and safer – ultrasound intensities, the researchers turned to gas vesicles (GVs), air-filled protein nanostructures that can be used as ultrasound contrast agents. They hypothesized that the GVs could function as acousto-mechanical transducers to focus the ultrasound energy: when exposed to FUS, the GVs undergo cavitation with the resulting energy activating the mechanophore.

PCs are no longer the massive beige boxes that sit on your desk taking up a massive amount of working real estate. Thanks to modernization and miniaturization, PCs can now fit into a tiny box.

How tiny?

Well, a hockey puck is 3 inches in diameter and an inch thick, which is not a lot bigger than the Blackview MP80.

Need a powerful Windows 11 PC that’s not much bigger than a hockey puck and won’t cost you much? Then the Blackview MP80 is the mini PC for you.

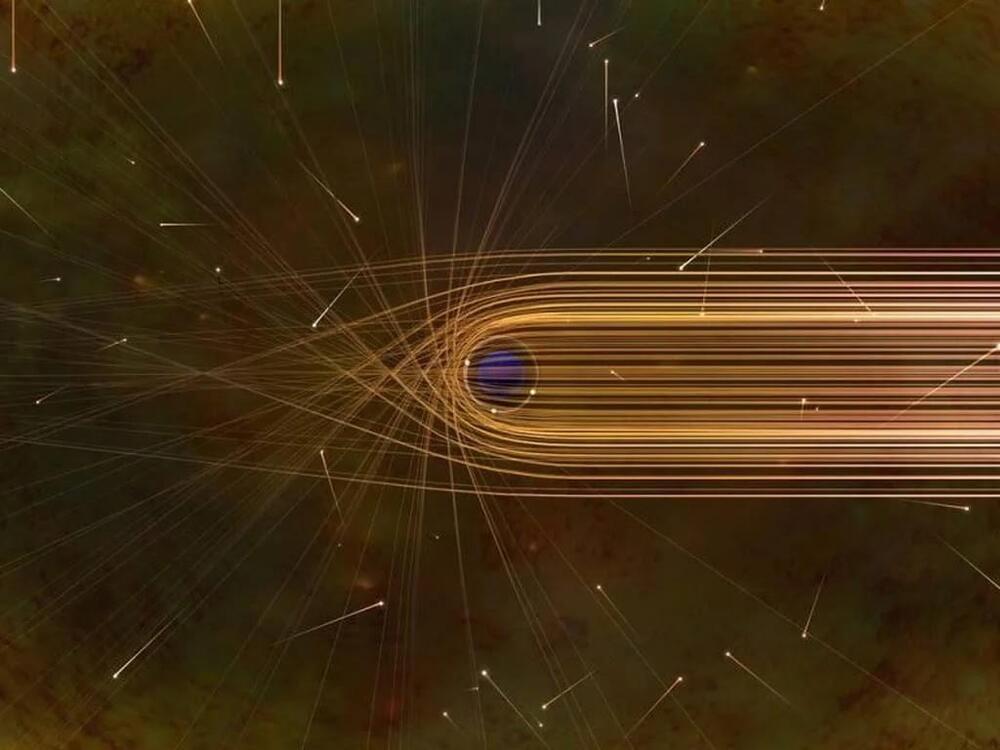

Agriculture in Syria started with a bang 12,800 years ago as a fragmented comet slammed into the Earth’s atmosphere. The explosion and subsequent environmental changes forced hunter-gatherers in the prehistoric settlement of Abu Hureyra to adopt agricultural practices to boost their chances for survival.

That’s the assertion made by an international group of scientists in one of four related research papers, all appearing in the journal Science Open: Airbursts and Cratering Impacts. The papers are the latest results in the investigation of the Younger Dryas Impact Hypothesis, the idea that an anomalous cooling of the Earth almost 13 millennia ago was the result of a cosmic impact.

“In this general region, there was a change from more humid conditions that were forested and with diverse sources of food for hunter-gatherers, to drier, cooler conditions when they could no longer subsist only as hunter-gatherers,” said Earth scientist James Kennett, a professor emeritus of UC Santa Barbara. The settlement at Abu Hureyra is famous among archaeologists for its evidence of the earliest known transition from foraging to farming. “The villagers started to cultivate barley, wheat and legumes,” he noted. “This is what the evidence clearly shows.”