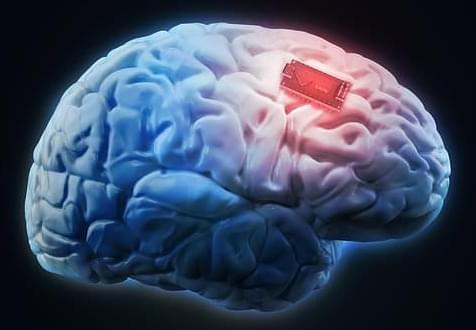

(Medical Xpress)—A team of researchers working at the University of Rochester in New York, has found that injecting glial cells into a mouse brain caused an improvement in both memory and cognition in the mouse. In their paper published in The Journal of Neuroscience, the team explains how they injected the test mice and then tested them afterwards to see what impact it had on their abilities.

Injecting human brain cells into mice brains appears to be the stuff of horror films, but in this case, it wasn’t really what it might have seemed. Glial cells are precursors to other cells—in this case, they develop into astrocytes, which are technically, brain cells. But, the important distinction here is that they are not neurons, which means they are not involved in thinking—instead they are involved in memory retention and help with housekeeping tasks.

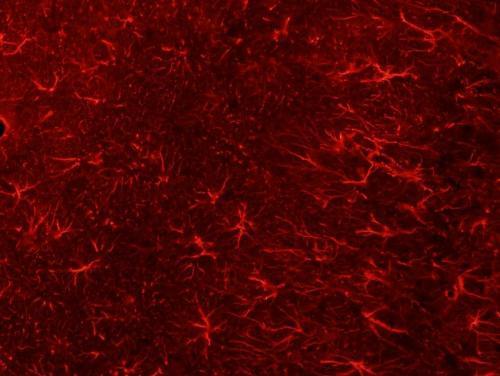

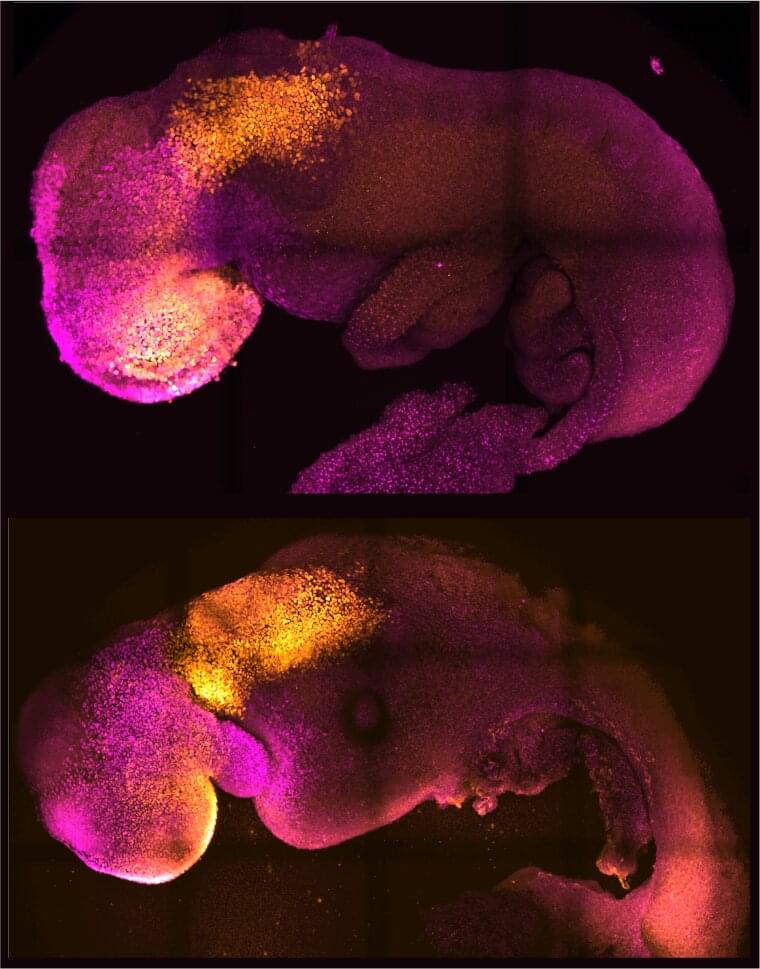

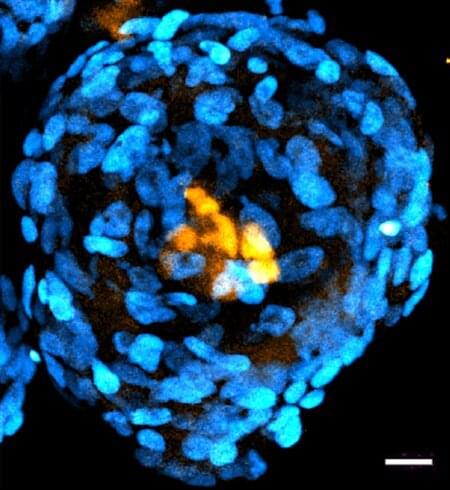

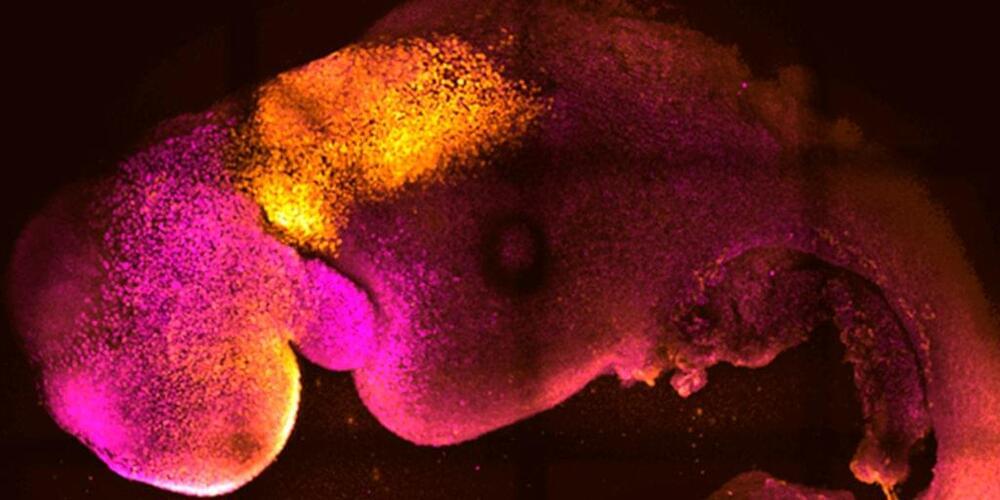

Last year, the team injected mature glial cells into mice brains and reported improvements in ability by the mice—this time they went further, injecting progenitor precursor glial cells, which allows for development of more astrocytes. The team injected just 300,000 of the cells (from donated human embryos) and found just 12 months later that they had multiplied to grow to 12 million, completely displacing the original mouse astrocytes. It appeared, the team reported, that the cell growth only stopped when it reached the physical confines of the skull. They also note that it was interesting that the glial could thrive in such an environment considering that astrocytess in people are 10 to 20 times as big as those in mice and they carry 100 times as many tendrils. Testing the mice showed that their memory was far superior to normal mice and they had improved cognition as well.