Year 2020 o.o!

A French startup has developed a urine-powered fertiliser that could limit our environmental footprints. Now it’s on a quest to find as much urine as possible.

New chemistry, new enzymology. With a new method that merges the best of two worlds—the unique and complementary activities of enzymes and small-molecule photochemistry—researchers at UC Santa Barbara have opened the door to new catalytic reactions. Their synergistic method allows for new products and can streamline existing processes, in particular, the synthesis of non-canonical amino acids, which are important for therapeutic purposes.

“This method solves what in my opinion is one of the most important problems in our field: how to develop new catalytic reactions in a general sense that are new to both biology and chemistry,” said chemistry Professor Yang Yang, an author of a paper that appears in the journal Science. “On top of that, the process is stereoselective, meaning it can select for a preferred “shape” of the resulting amino acid.”

The synergistic photobiocatalytic method consists of two co-occurring catalytic reactions. The photochemical reaction generates a short-lived intermediate molecule that works with the reactive intermediate of the enzymatic process, resulting in the amino acid.

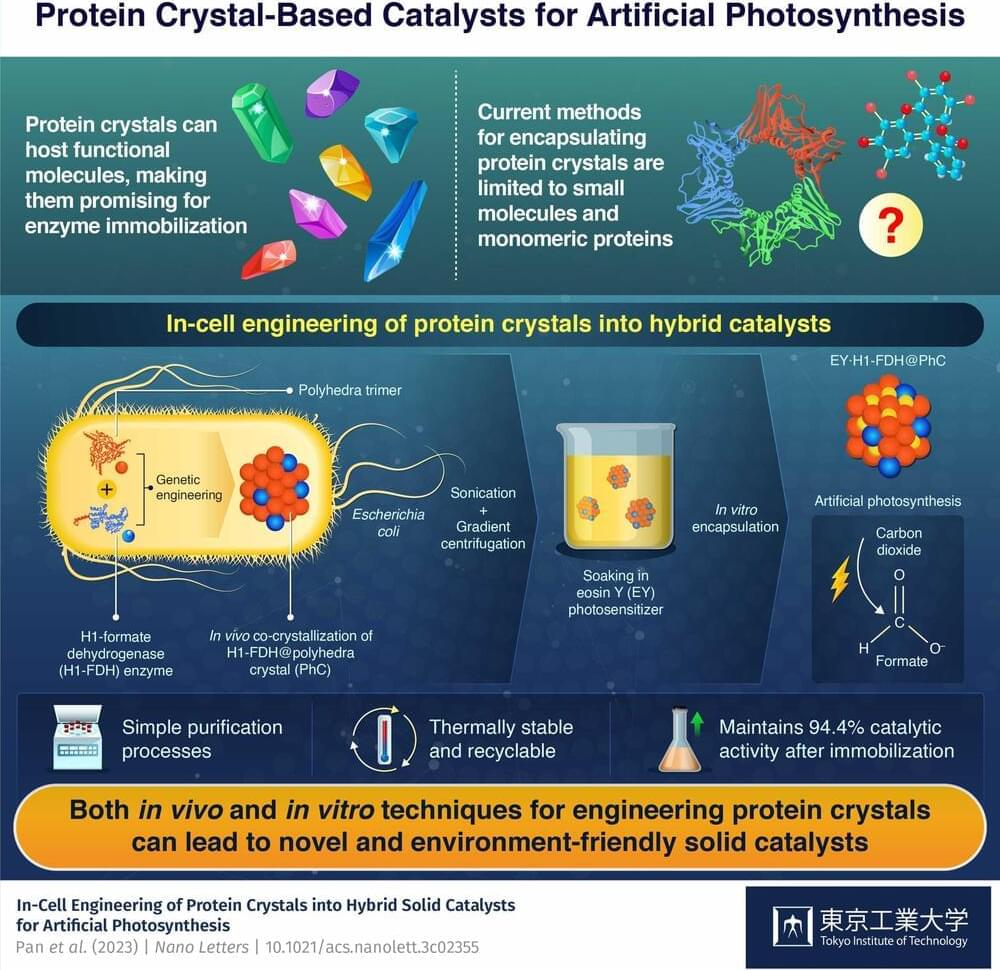

In-cell engineering can be a powerful tool for synthesizing functional protein crystals with promising catalytic properties, show researchers at Tokyo Tech. Using genetically modified bacteria as an environmentally friendly synthesis platform, the researchers produced hybrid solid catalysts for artificial photosynthesis. These catalysts exhibit high activity, stability, and durability, highlighting the potential of the proposed innovative approach.

Protein crystals, like regular crystals, are well-ordered molecular structures with diverse properties and a huge potential for customization. They can assemble naturally from materials found within cells, which not only greatly reduces the synthesis costs but also lessens their environmental impact.

Although protein crystals are promising as catalysts because they can host various functional molecules, current techniques only enable the attachment of small molecules and simple proteins. Thus, it is imperative to find ways to produce protein crystals bearing both natural enzymes and synthetic functional molecules to tap their full potential for enzyme immobilization.

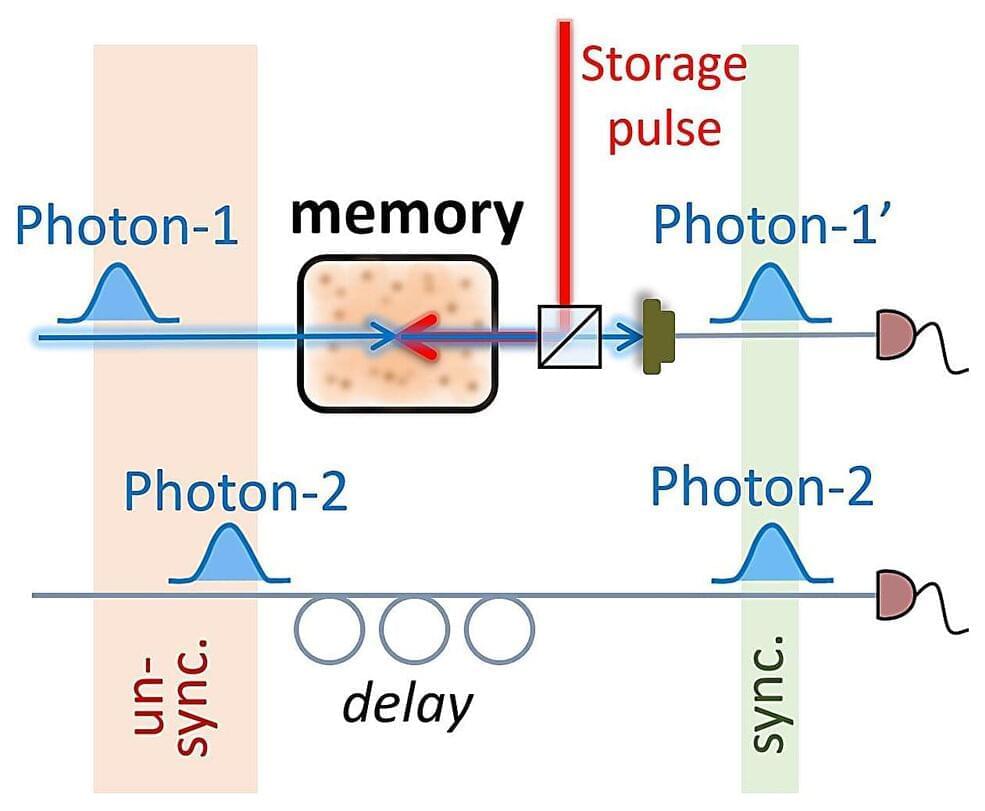

A long-standing challenge in the field of quantum physics is the efficient synchronization of individual and independently generated photons (i.e., light particles). Realizing this would have crucial implications for quantum information processing that relies on interactions between multiple photons.

Researchers at Weizmann Institute of Science recently demonstrated the synchronization of single, independently generated photons using an atomic quantum memory operating at room-temperature. Their paper, published in Physical Review Letters, could open new avenues for the study of multi-photon states and their use in quantum information processing.

“The project idea came about several years ago, when our group and the group of Ian Walmsley demonstrated an atomic quantum memory with an inverted atomic-level scheme compared to the typical memories—the ladder memory, named fast ladder memory (FLAME),” Omri Davidson, one of the researchers who carried out the study, told Phys.org. “These memories are fast and noise-free, and therefore they are useful for synchronization of single photons.”

Reducing reliance of aninmal experimentation. 🐀

According to the team, this new unparalleled technology facilitates the precise manipulation of biological materials, enabling the creation of highly sophisticated and realistic organoids that closely mimic the complexity of the corresponding human organs.

The cutting-edge magnetic and acoustic levitation will bioprint heart models to improve protection against radiation both in space and on Earth.

After being awarded nearly 4 million euros by the European Innovation Council’s Pathfinder Open, PULSE is aiming to foster technological innovations to improve human health and pave the way for safer and more sustainable space exploration.

Multi-Levitation bioprinting and creating realistic organoids

The device, designed by PULSE, combines magnetic and acoustic levitation into an innovative bioprinting platform capable spatiotemporal control of cell deposition.

When the scaffold is treated with a steroid called fluocinolone acetonide, which protects against inflammation, the resilience of the cells appears to increase, promoting growth of eye cells. These findings are important in the future development of ocular tissue for transplantation into the patient’s eye.

Scientists have found a way to use nanotechnology to create a 3D ‘scaffold’ to grow cells from the retina-paving the way for potential new ways of treating a common cause of blindness.

Researchers, led by Professor Barbara Pierscionek from Anglia Ruskin University (ARU), have been working on a way to successfully grow retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells that stay healthy and viable for up to 150 days. RPE cells sit just outside the neural part of the retina and, when damaged, can cause vision to deteriorate.

It is the first time this technology, called ‘electrospinning’, has been used to create a scaffold on which the RPE cells could grow, and could revolutionise treatment for one of age-related macular degeneration, one of the world’s most common vision complaints.