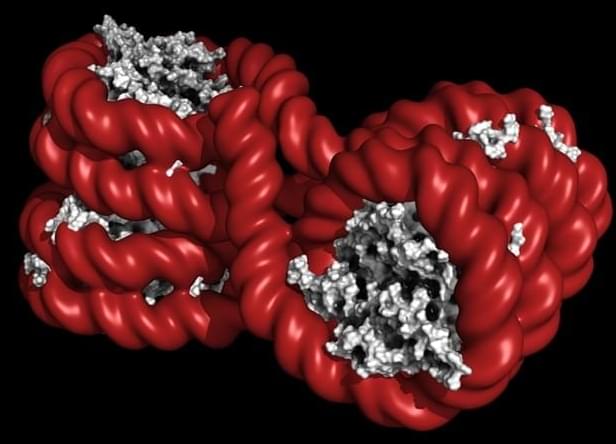

Epigenetics, the chemical mechanisms that controls the activity of genes, allows our cells, tissues and organs to adapt to the changing circumstances of the environment around us. This advantage can become a drawback, though, as this epigenetic regulation can be more easily altered by toxins than the more stable genetic sequence of the DNA.

An article recently published at Science with the collaboration of the groups of Dr. Manel Esteller, Director of the Josep Carreras Leukaemia Research Institute (IJC-CERCA), ICREA Research Professor and Chairman of Genetics at the University of Barcelona, and Dr. Lucas Pontel, Ramon y Cajal Fellow also of the Josep Carreras Institute, demonstrates that the substance called formaldehyde, commonly present in various household and cosmetic products, in polluted air, and widely used in construction, is a powerful modifier of normal epigenetic patterns.

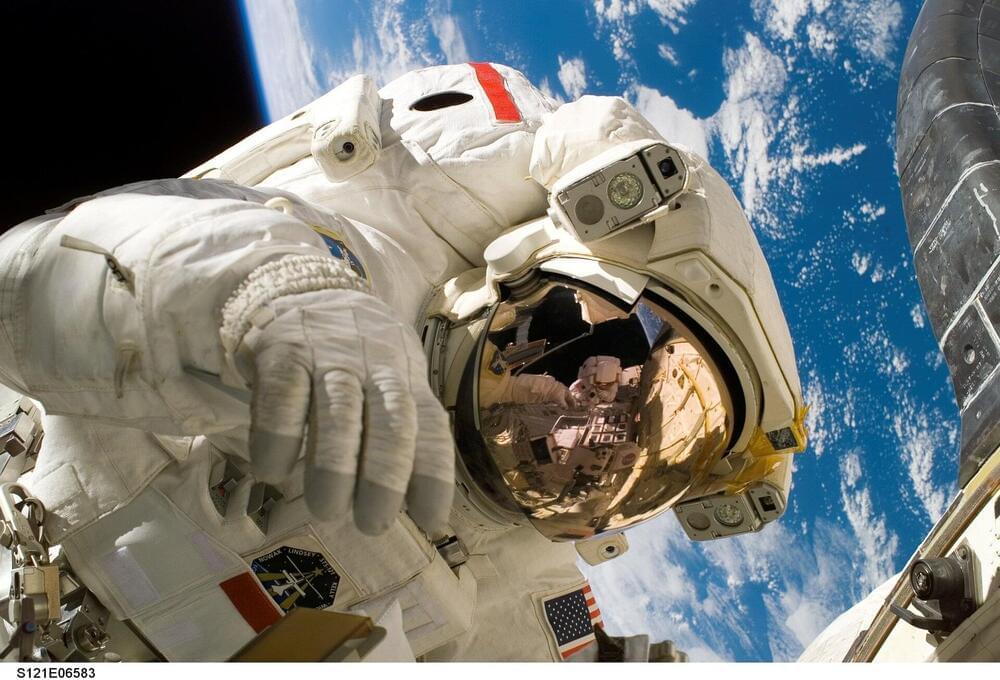

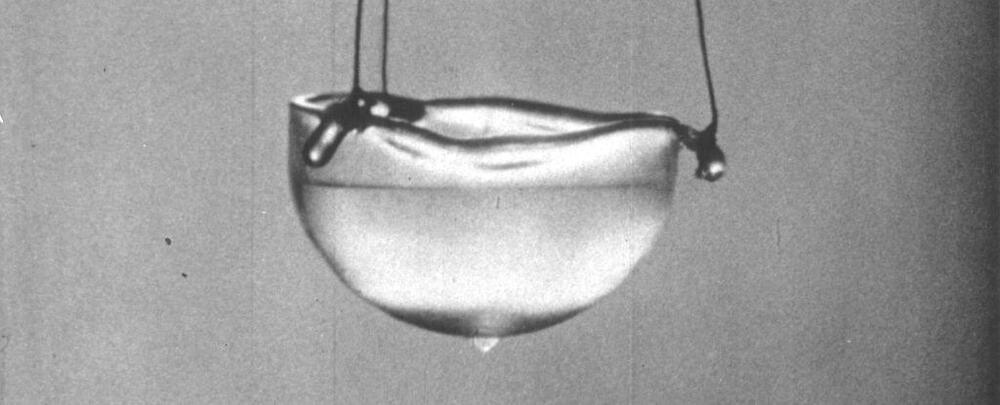

The publication is led by Dr. Christopher J. Chang, of the University of California Berkeley in the United States, whose research group is pioneer in the study of the effects of various chemical products on cell metabolism. The research has focused on investigating the effects of high concentrations of formaldehyde in the body, a substance already been associated with an increased risk of developing cancer (nasopharyngeal tumours and leukaemia), hepatic degeneration due to fatty liver (steatosis) and asthma. Dr. Esteller points out that this is relevant because “formaldehyde enters our body mainly during our breathing and, because it dissolves well in an aqueous medium, it ends up reaching all the cells of our body”.