The first asteroid sample collected in space by a U.S. spacecraft and brought to Earth is unveiled to the world at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston on…

Get the latest international news and world events from around the world.

NASA wants a ‘lunar freezer’ for its Artemis moon missions

NASA has issued a request for “lunar freezer” designs that can safely store materials taken from the moon during planned Artemis missions.

According to a request for information (RFI) posted to the federal contracting website SAM.gov, the freezer’s primary use will be transporting scientific and geological samples from the moon to Earth. These samples, the post specifies, will be ones collected during the Artemis program.

Humane’s ‘AI Pin’ debuts on the Paris runway

Humane, a stealthy software and hardware company, is clearly milking the media hype cycle for all it’s worth. The company’s origin dates all the way back to 2017, when it was founded by former Apple employees Bethany Bongiorno and Imran Chaudhri. In the intervening half-decade, the firm has been largely shrouded in mystery, as it has put together the pieces of a mystery wearable, which it promises will leverage AI in unique ways.

The company’s been buzzy since it first engaged with the media — well before it offered the slightest bit of insight into what it’s been working on. In spite — or perhaps because — of such mysteries, Humane is now an extremely well-funded early-stage startup.

At the tail end of 2020, it raised a $30 million Series A at a $150 million valuation. The $100 million B round arrived the following September, including Tiger Global Management, SoftBank Group, BOND, Forerunner Ventures and Qualcomm Ventures. It all seemed like a strong vote of confidence for the still stealthy firm. This March, it went ahead and raised another $100 million.

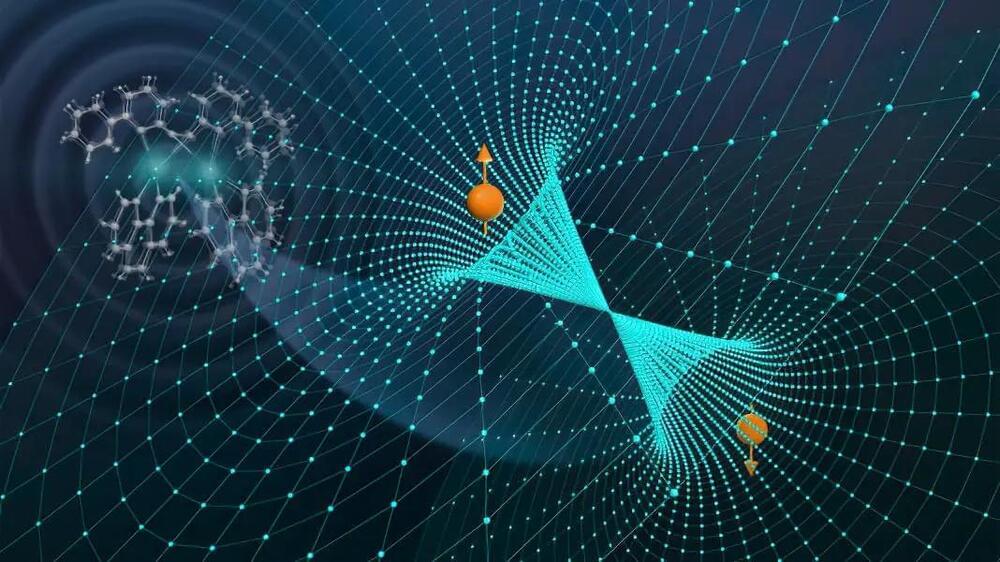

Breaking the Born-Oppenheimer Approximation — Experiments Unveil Long-Theorized Quantum Phenomenon

Nearly a century ago, physicists Max Born and J. Robert Oppenheimer developed a hypothesis about the functioning of quantum mechanics within molecules. These molecules consist of complex systems of nuclei and electrons. The Born-Oppenheimer approximation postulates that the movements of nuclei and electrons within a molecule occur independently and can treated separately.

This model works the vast majority of the time, but scientists are testing its limits. Recently, a team of scientists demonstrated the breakdown of this assumption on very fast time scales, revealing a close relationship between the dynamics of nuclei and electrons. The discovery could influence the design of molecules useful for solar energy conversion, energy production, quantum information science, and more.

The team, including scientists from the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Argonne National Laboratory, Northwestern University, North Carolina State University, and the University of Washington, recently published their discovery in two related papers in Nature and Angewandte Chemie International Edition.

Cancer, Metabolism, and Food: A New Way to Look at Potential Therapies

Cancer relies on metabolism pathways to grow, which has Rogel Cancer Center researchers looking at how to use food and diet to exploit cancer’s vulnerabilities as a foundation of new potential therapies.

Learn more about the cancer research being done at University of Michigan Health Rogel Cancer Center: https://www.rogelcancercenter.org/research/programs.

Follow michigan medicine on social media:

Twitter: https://twitter.com/umichmedicine.

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/umichmedicine/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/MichiganMedicine/

Follow the Rogel Cancer Center at Michigan Medicine on Social Media:

Twitter: https://twitter.com/umrogelcancer.

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/UMRogelCancerCenter/

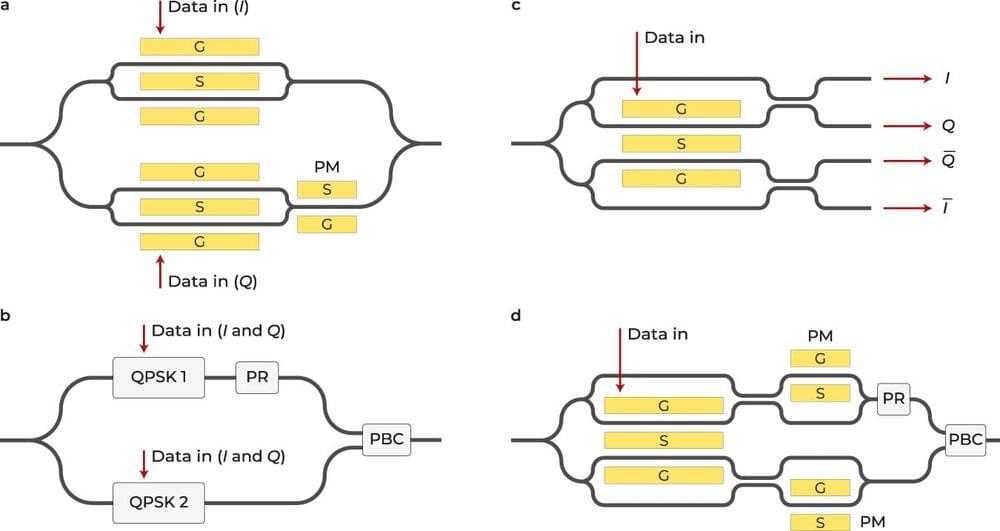

New technology could reduce lag, improve reliability of online gaming, meetings

Whether you’re battling foes in a virtual arena or collaborating with colleagues across the globe, lag-induced disruptions can be a major hindrance to seamless communication and immersive experiences.

That’s why researchers with the University of Central Florida’s College of Optics and Photonics (CREOL) and the University of California, Los Angeles, have developed new technology to make data transfer over optical fiber communication faster and more efficient.

Their new development, a novel class of optical modulators, is detailed in a new study published recently in the journal Nature Communications. Modulators can be thought of as like a light switch that controls certain properties of data-carrying light in an optical communication system.

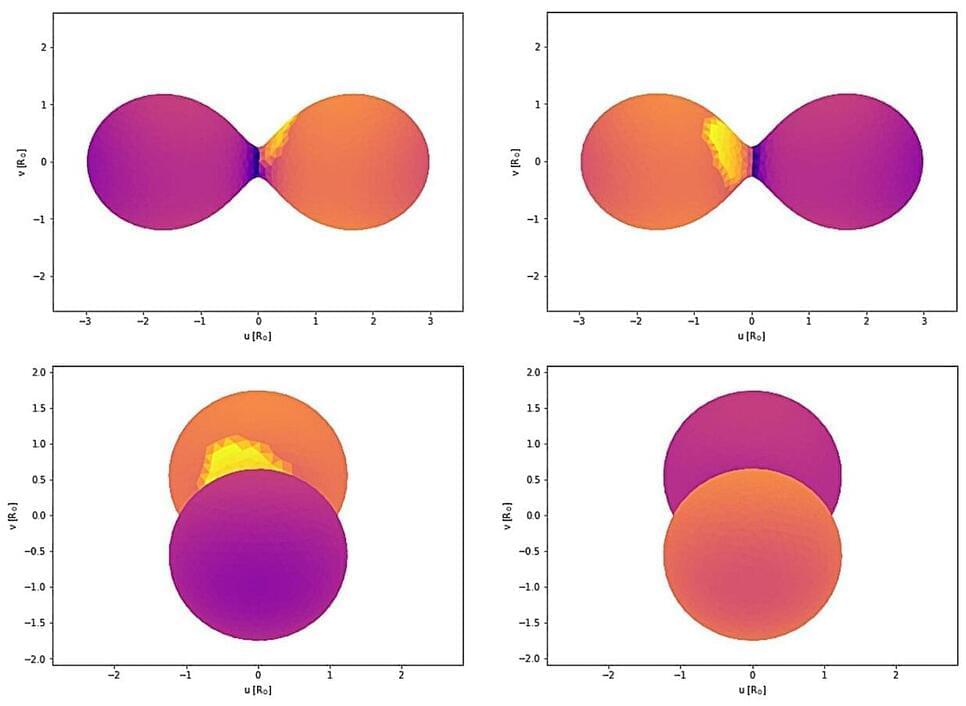

V0610 Virgo is a low-mass contact binary, observations find

Astronomers from the Binary Systems of South and North (BSN) project have conducted photometric observations of a distant binary star known as V0610 Virgo. Results of the observation campaign, published Sept. 23 in a research paper on the pre-print server arXiv, indicate that V0610 Virgo is a low-mass contact binary system.

W Ursae Majoris-type, or W UMa-type binaries (EWs) are eclipsing binaries with a short orbital period (below one day) and continuous light variation during a cycle. They are also known as “contact binaries,” given that these systems are composed of two dwarf stars with similar temperature and luminosity, sharing a common envelope of material and are thus in contact with one another. In general, studies of contact binaries have the potential to reveal many details about the evolution of stars.

Located some 1,560 light years away from the Earth, V0610 Virgo is an EW with an apparent magnitude of 13.3 mag. Although not much is known about this system, previous observations have found that it has an orbital period of approximately eight hours.

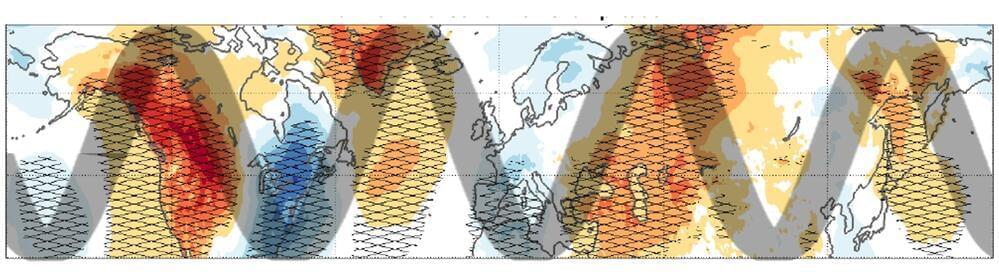

Study identifies jet-stream pattern that locks in extreme winter cold, wet spells

Winter is coming—eventually. And while the Earth is warming, a new study suggests that the atmosphere is being pushed around in ways that cause long bouts of extreme winter cold or wet in some regions.

The study’s authors say they have identified giant meanders in the global jet stream that bring polar air southward, locking in frigid or wet conditions concurrently over much of North America and Europe, often for weeks at a time. Such weather waves, they say, have doubled in frequency since the 1960s. In just the last few years, they have killed hundreds of people and paralyzed energy and transport systems.

The new paper, titled “Recent Increase in a Recurrent Pan-Atlantic Wave Pattern Driving Concurrent Wintertime Extremes,” appears this week in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society.

Software can detect hidden and complex emotions in parents

Researchers have conducted trials using a software capable of detecting intricate details of emotions that remain hidden to the human eye.

The software, which uses an “artificial net” to map key features of the face, can evaluate the intensities of multiple different facial expressions simultaneously.

The University of Bristol and Manchester Metropolitan University team worked with Bristol’s Children of the 90s study participants to see how well computational methods could capture authentic human emotions amidst everyday family life. This included the use of videos taken at home, captured by headcams worn by babies during interactions with their parents.

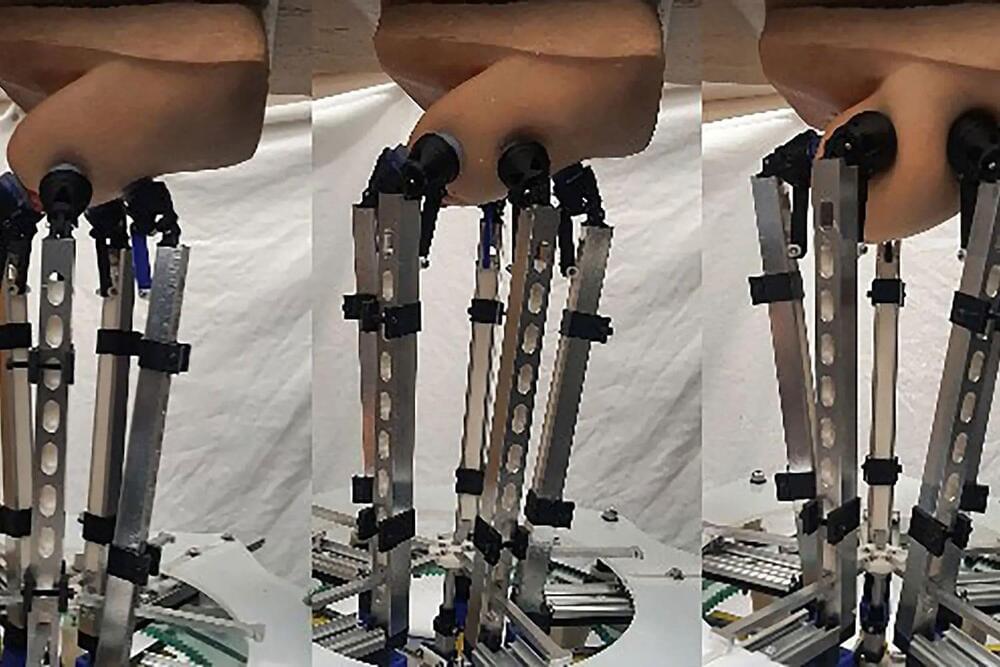

New robot could help diagnose breast cancer at an early stage

“We hope that the research can contribute to and complement the arsenal of techniques used to diagnose breast cancer and to generate a large amount of data associated with it that may be useful in trying to identify large-scale trends that could help diagnose breast cancer early,” George added.

The team next plans to combine CBE techniques learned from professionals with AI and fully equip IRIS with sensors to determine the effectiveness of the whole system in identifying potential cancer risks. The ultimate goal is to have the manipulator detect lumps more accurately and deeper than it is possible only by applying human touch.

This promising development could revolutionize how women monitor their breast health. With safe electronic CBEs located in easily accessible places like pharmacies and health centers, women could have access to accurate results and take a proactive approach to their health.