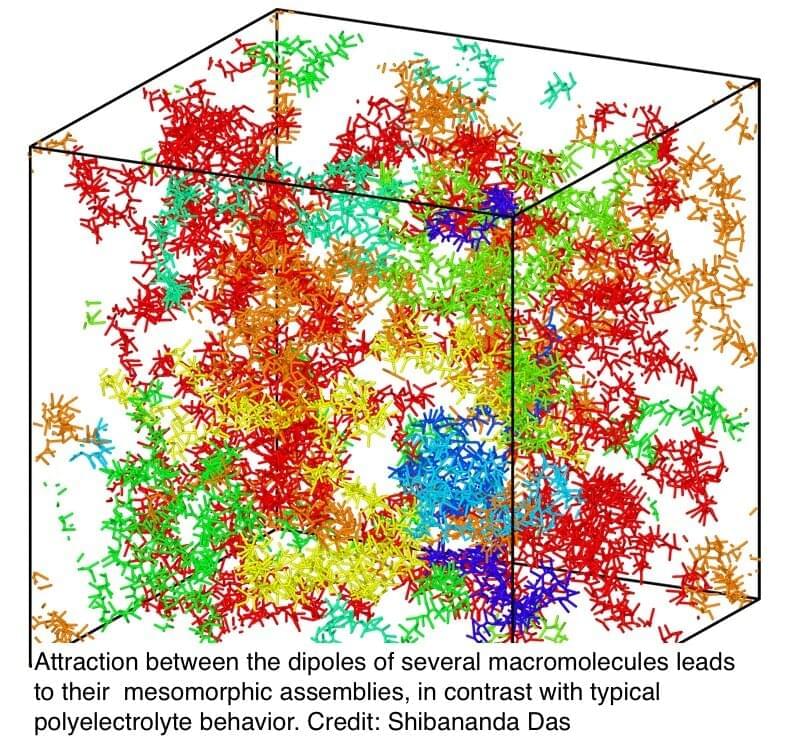

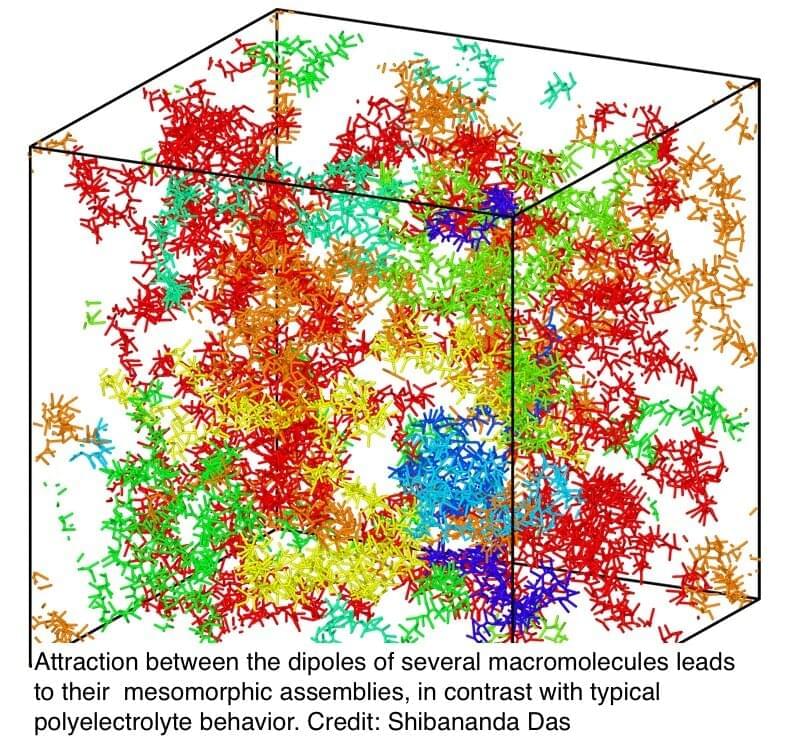

In a discovery with wide-ranging implications, researchers at the University of Massachusetts Amherst recently announced in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that uniformly charged macromolecules—or molecules, such as proteins or DNA, that contain a large number of atoms all with the same electrical charge—can self-assemble into very large structures. This finding upends our understanding of how some of life’s basic structures are built.

Traditionally, scientists have understood charged polymer chains as being composed of smaller, uniformly charged units. Such chains, called polyelectrolytes, display predictable behaviors of self-organization in water: They will repel each other because similarly charged objects don’t like to be close to each other. If you add salt to water containing polyelectrolytes, then molecules coil up, because the chains’ electrical repulsion is screened by the salt.

However, “the game is very different when you have dipoles,” says Murugappan Muthukumar, the Wilmer D. Barrett Professor in Polymer Science and Engineering at UMass Amherst, the study’s senior author.