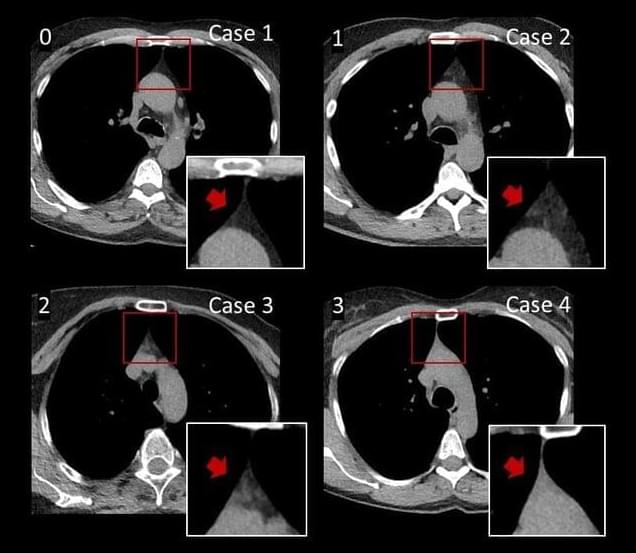

The thymus, a small and relatively unknown organ, may play a bigger role in the immune system of adults than was previously believed. With age, the glandular tissue in the thymus is replaced by fat, but, according to a new study from Linköping University, the rate at which this happens is linked to sex, age and lifestyle factors. These findings also indicate that the appearance of the thymus reflects the aging of the immune system.

“We doctors can assess the appearance of the thymus from largely all chest CT scans, but we tend to not see this as very important. But now it turns out that the appearance of the thymus can actually provide a lot of valuable information that we could benefit from and learn more about,” says Mårten Sandstedt, MD, Ph.D., at the Department of Radiology in Linköping and Department of Health, Medicine and Caring Sciences, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Linköping University.

The thymus is a gland located in the upper part of the chest. It has been long known that this small organ is important for immune defense development in children. After puberty, the thymus decreases in size and is eventually replaced by fat, in a process known as fatty degeneration. This has been taken to mean that it loses its function, which is why the thymus has for a long time been considered as being not important in adult life.