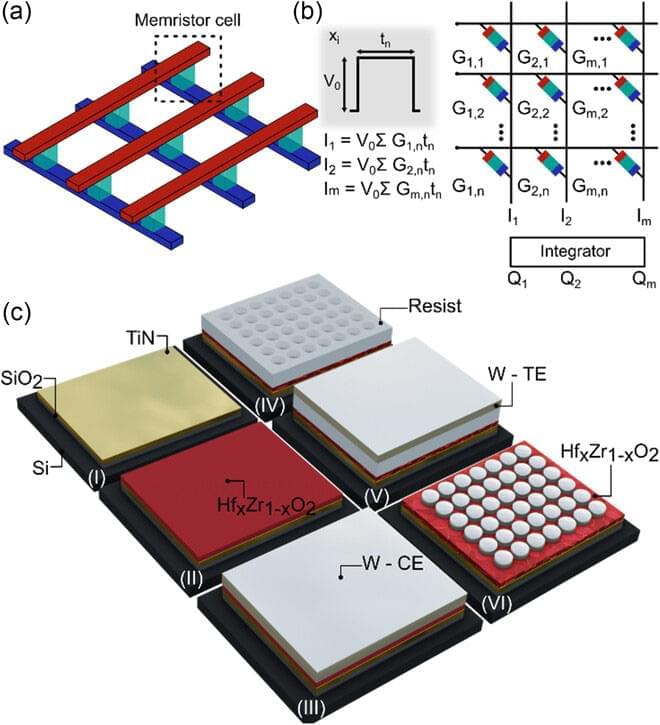

Recent research realizes ferroelectric hafnium oxide memristors with ultra-low conductance and inherent current-voltage nonlinearity to mitigate limitations that have obstructed commercialization of brain-inspired neuromorphic hardware.

Southern Company has a historic commitment to energy innovation. Since the 1960s, the company has invested well over $2 billion in research and development (R&D), and currently, their employees are on the forefront of delivering new ideas to build the future of energy.

Enter Spot—an agile robot. Chethan Acharya, a principal research engineer within Southern Company R&D, first discovered Spot on social media.

At the time, Acharya’s job was to find and test new sensors, analytics tools, and other solutions to help Southern Company improve operations and maintenance (O&M) activities while also lowering costs.

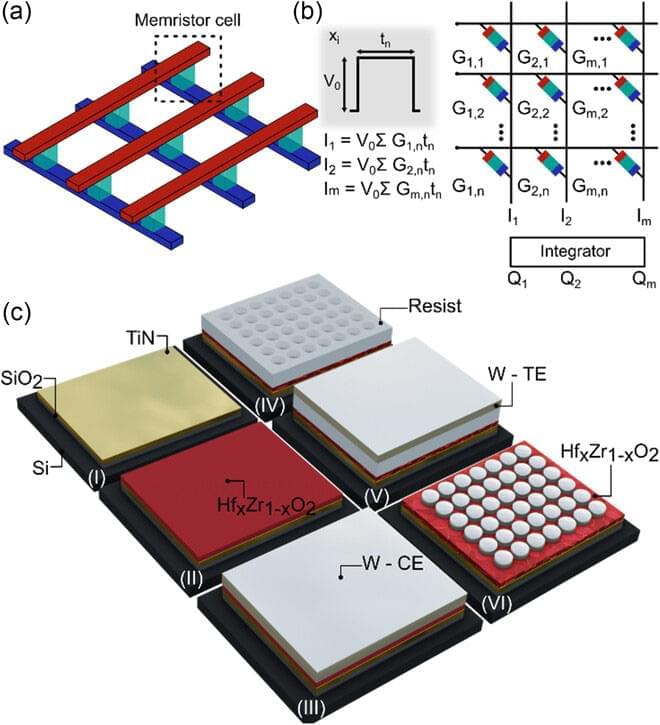

With the market for wearable electric devices growing rapidly, stretchable solar cells that can function under strain have received considerable attention as an energy source. To build such solar cells, it is necessary that their photoactive layer, which converts light into electricity, shows high electrical performance while possessing mechanical elasticity. However, satisfying both of these two requirements is challenging, making stretchable solar cells difficult to develop.

A KAIST research team from the Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering (CBE) led by Professor Bumjoon Kim announced the development of a new conductive polymer material that achieved both high electrical performance and elasticity while introducing the world’s highest-performing stretchable organic solar cell.

Figure 1. Chemical structure of the newly developed conductive polymer and performance of stretchable organic solar cells using the material. (Image: KAIST)

The commercial space industry recently received a boost after NASA awarded 10 small businesses up to $150,000 each as part of NASA’s Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) Ignite program, granting each company six months to demonstrate the viability and additional standards of their mission proposals. This funding comes as part of the second round of Phase I awards and holds the potential to continue the development of the commercial space industry for the short-and long-term.

“The investments we’re able to offer through SBIR Ignite give us the ability to de-risk technologies that have a strong commercial pull, helping make them more attractive to outside investors, customers, and partners,” said Jason L. Kessler, who is the Program Executive for the NASA SBIR & Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) Program. “We also hope it advances the sometimes-overlooked goal of all SBIR programs to increase private-sector commercialization of the innovations derived from federal research and development funding.”

The 10 companies selected for this latest round of funding include (in alphabetical order): Astral Forge LLC, Astrobotic Technology Inc., Benchmark Space Systems, Brayton Energy LLC, Channel-Logistics LLC dba Space-Eyes, GeoVisual Analytics, Lunar Resources Inc., Space Lab Technologies LLC, Space Tango, and VerdeGo Aero.

Reminds me of how the space shuttle moved in orbit. Great idea though hopefully they’ll pass it on to us civilians too. That could be very useful. Though the military sometimes passes their tech to us like the CIA is responsible for some medical science amazingly. Yes I was surprised.

DARPA has selected Aurora Flight Sciences to build a full-scale X-plane to demonstrate the viability of using active flow control (AFC) actuators for primary flight control. The award is Phase 3 of the Control of Revolutionary Aircraft with Novel Effectors (CRANE) program.

The X-65 flight is controlled by using jets of air from a pressurized source to shape the flow of air over the aircraft surface, with AFC effectors on several surfaces to control the plane’s roll, pitch, and yaw. Eliminating external moving parts is expected to reduce weight and complexity and to improve performance.

The X-65 will be built with two sets of control actuators – traditional flaps and rudders as well as AFC effectors embedded across all the lifting surfaces. This will both minimize risk and maximize the program’s insight into control effectiveness. The plane’s performance with traditional control surfaces will serve as a baseline; successive tests will selectively lock down moving surfaces, using AFC effectors instead.

John Preskill, Richard P. Feynman Professor of Theoretical Physics and Director, Institute for Quantum Information and Matter, California Institute of Technology | Crossing the Quantum Chasm: From NISQ to Fault Tolerance.

Year 2023 face_with_colon_three

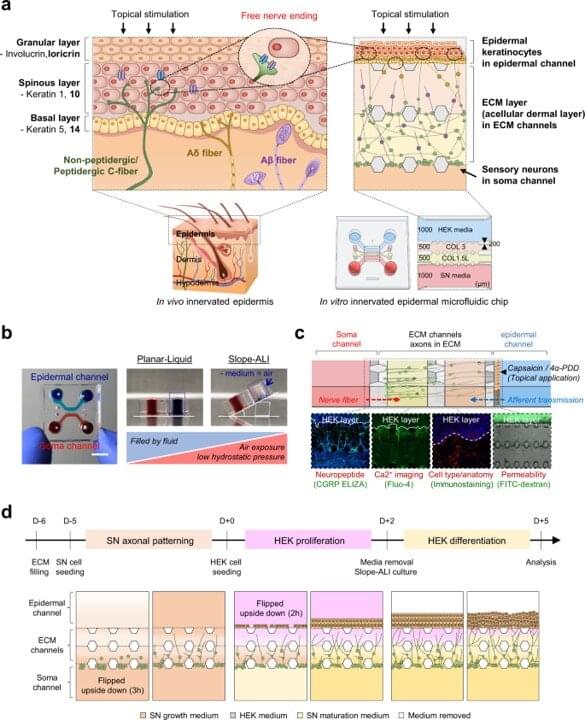

Bioengineers and tissue engineers intend to reconstruct skin equivalents with physiologically relevant cellular and matrix architectures for basic research and industrial applications. Skin pathophysiology depends on skin-nerve crosstalk and researchers must therefore develop reliable models of skin in the lab to assess selective communications between epidermal keratinocytes and sensory neurons.

In a new report now published in Nature Communications, Jinchul Ahn and a research team in mechanical engineering, bio-convergence engineering, and therapeutics and biotechnology in South Korea presented a three-dimensional, innervated epidermal keratinocyte layer on a microfluidic chip to create a sensory neuron-epidermal keratinocyte co-culture model. The biological model maintained well-organized basal-suprabasal stratification and enhanced barrier function for physiologically relevant anatomical representation to show the feasibility of imaging in the lab, alongside functional analyses to improve the existing co-culture models. The platform is well-suited for biomedical and pharmaceutical research.

Skin: The largest sensory organ of the human body

Skin is composed of a complex network of sensory nerve fibers to form a highly sensitive organ with mechanoreceptors, thermoreceptors and nociceptors. These neuronal subtypes reside in the dorsal root ganglia and are densely and distinctly innervated into the cutaneous layers. Sensory nerve fibers in the skin also express and release nerve mediators including neuropeptides to signal the skin. The biological significance of nerves to sensations and other biological skin functions have formed physical and pathological correlations with several skin diseases, making these instruments apt in vivo models to emulate skin-nerve interactions.

CES has always been the place for weird, out-there gadgets to make their debuts, and this year’s show is no exception.

Skyted, a Toulouse, France-based startup founded by former Airbus VP Stéphane Hersen and acoustical engineer Frank Simon, is bringing what look like a pair of human muzzles to CES 2024. Called the “Mobility Privacy Mask” and “Hybrid Silent Mask,” the face-worn accoutrements are designed to “absorb voice frequencies” in noisy environments like plains, trains and rideshares, Hersen says.

“Skyted’s solution is ideal for commuters, business executives and travelers anywhere,” Hersen is quoted as saying in a press release. “No matter how busy or public the location is, they can now speak in silence and with the assurance that no one nearby can hear their conversation.”

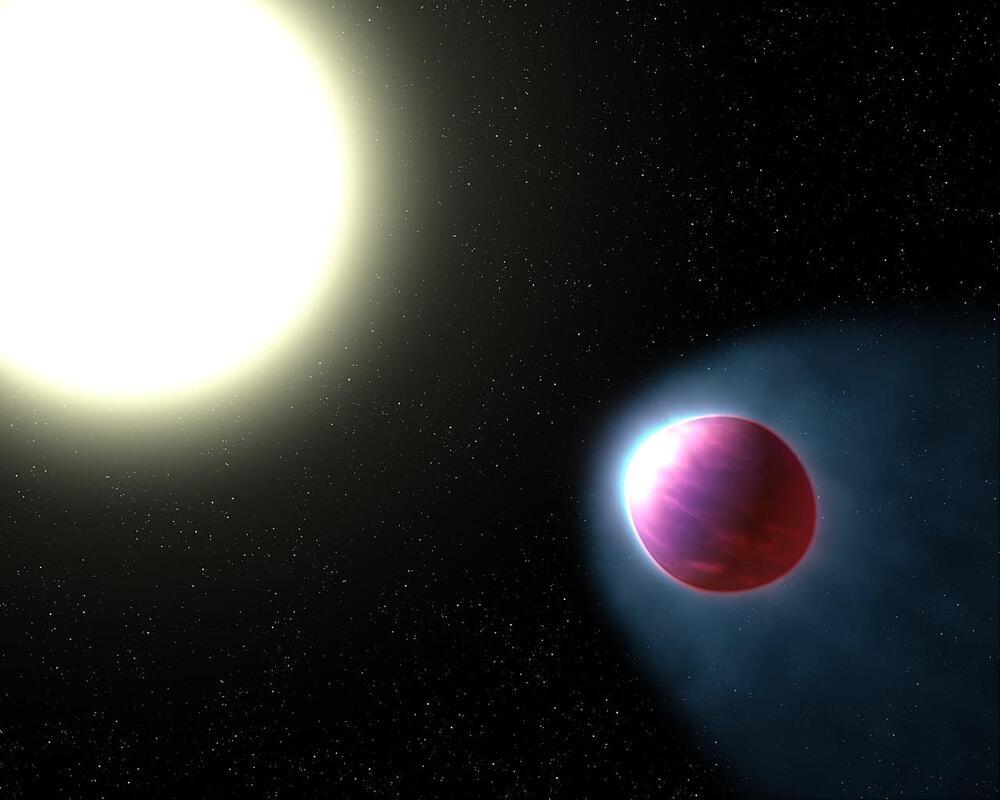

Meteorologists on Earth struggle to predict the weather, but what about scientists trying to predict the weather on exoplanets that are light-years from Earth? This is what a recently accepted study to The Astrophysical Journal Supplement hopes to unveil as an international team of researchers used data from NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope to conduct a three-year investigation into weather patterns on WASP-121 b, which is a “hot Jupiter” that orbits its star in just over one day and located approximately 880 light-years from Earth. This study holds the potential to not only advance our understanding of exoplanets and their atmospheres, but also how we study them, as well.

Artist impression of WASP-121 b orbiting its host star. (Credit: NASA, ESA, and G. Bacon (STSci))

“The assembled dataset represents a significant amount of observing time for a single planet and is currently the only consistent set of such repeated observations,” said Dr. Quentin Changeat, who is an Honorary Research Fellow in the Department of Astronomy at University College London and lead author of the study. “The information that we extracted from those observations was used to infer the chemistry, temperature, and clouds of the atmosphere of WASP-121 b at different times. This provided us with an exquisite picture of the planet changing over time.”