Enzymes with specific functions are becoming increasingly important in industry, medicine and environmental protection. For example, they make it possible to synthesize chemicals in a more environmentally friendly way, produce active ingredients in a targeted manner or break down environmentally harmful substances.

Researchers from Gustav Oberdorfer’s working group at the Institute of Biochemistry at Graz University of Technology (TU Graz), together with colleagues from the University of Graz, have now published a study in Nature describing a new method for the design of customized enzymes.

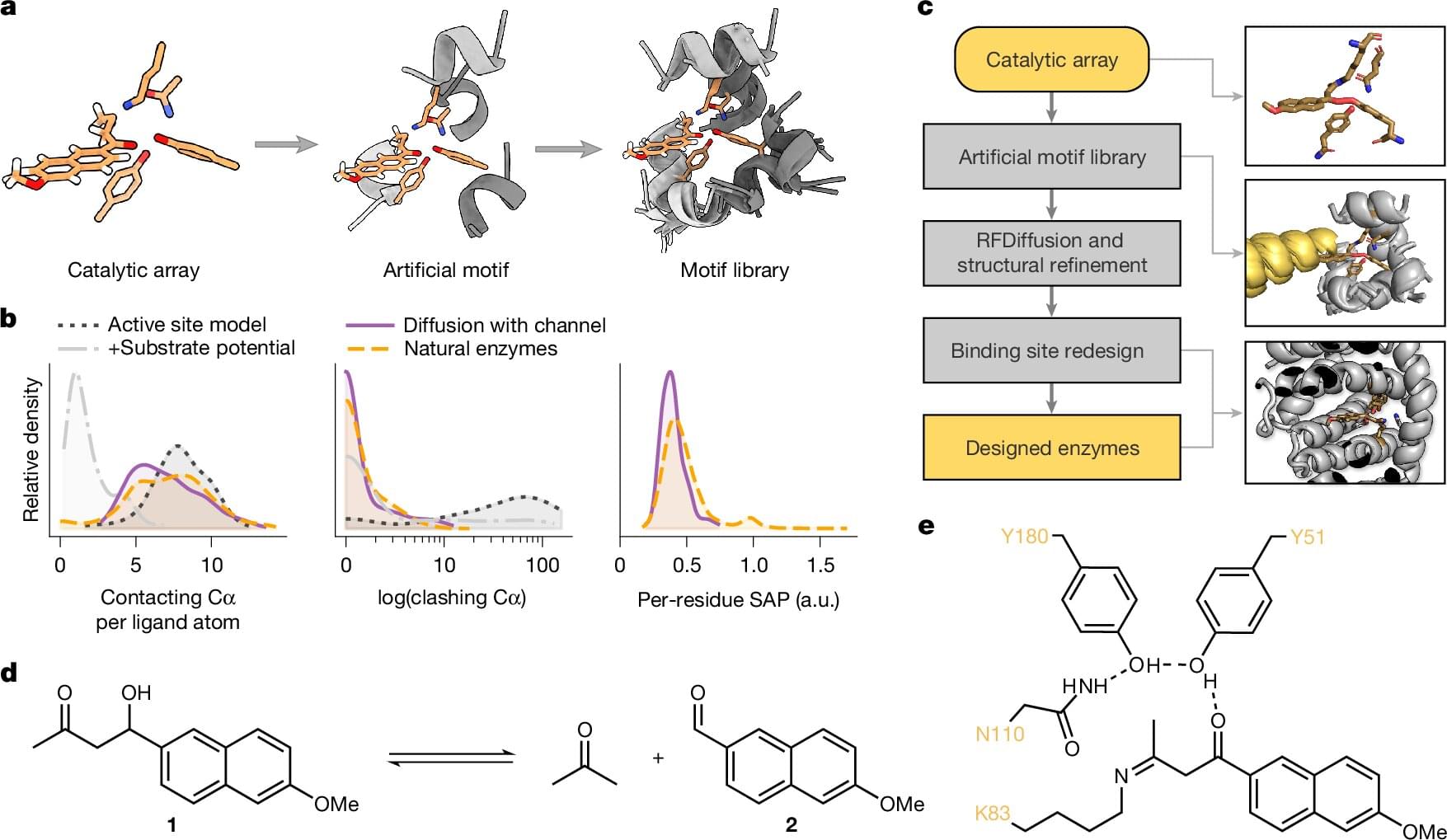

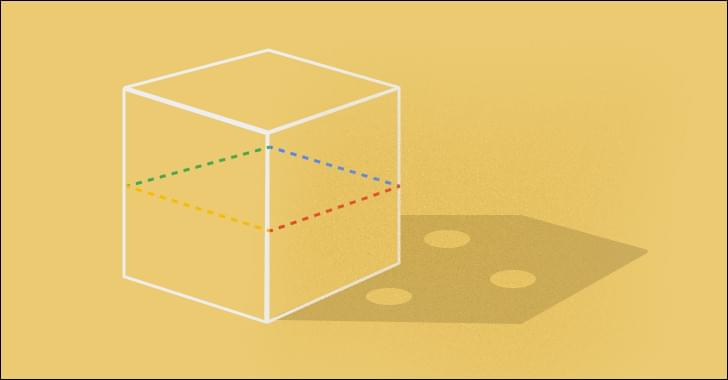

The technology called Riff-Diff (Rotamer Inverted Fragment Finder–Diffusion) makes it possible to accurately and efficiently build the protein structure specifically around the active center instead of searching for a suitable structure from existing databases. The resulting enzymes are not only significantly more active than previous artificial enzymes, but also more stable.