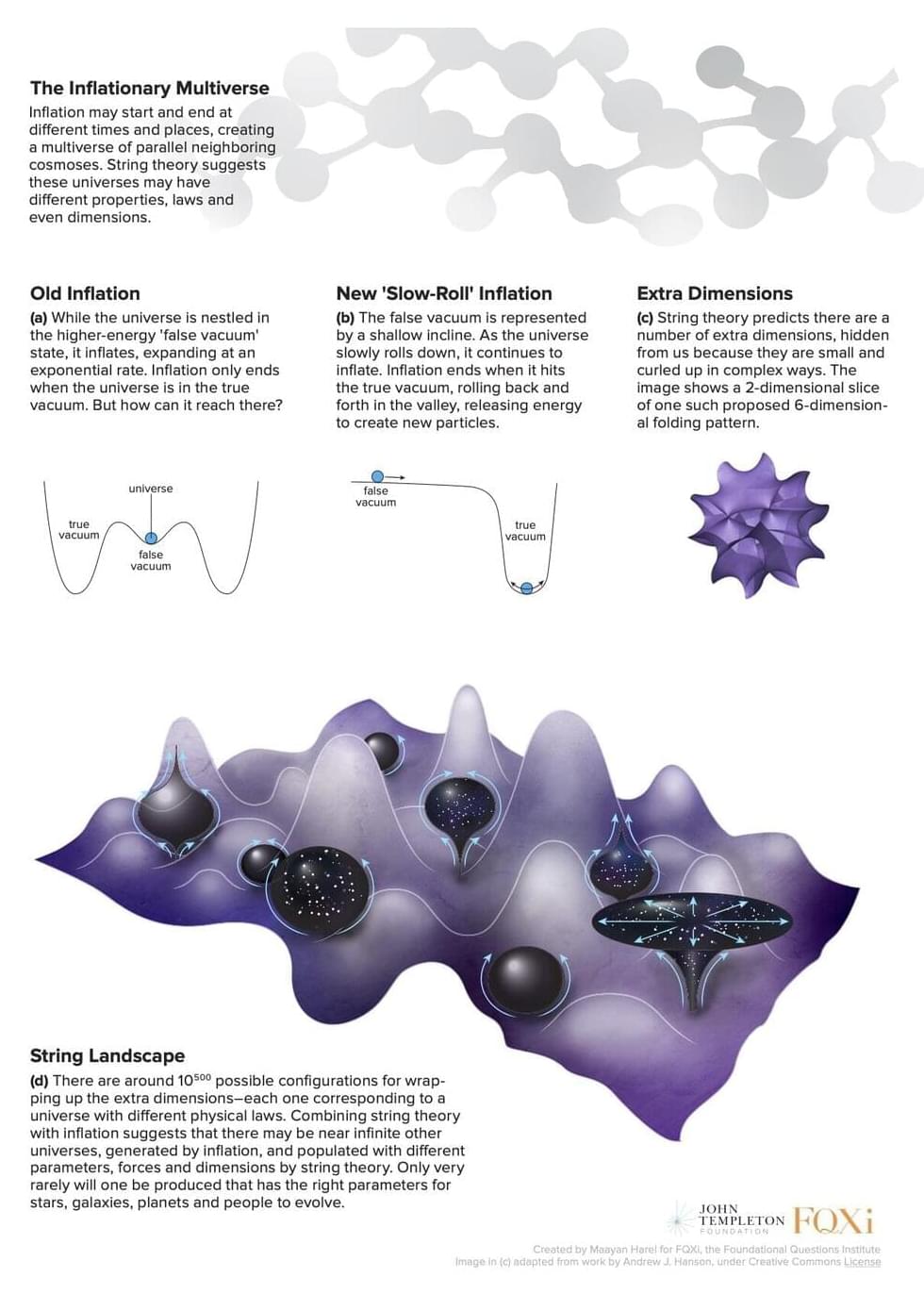

For decades physicists have been perplexed about why our cosmos appears to have been precisely tuned to foster intelligent life. It is widely thought that if the values of certain physical parameters, such as the masses of elementary particles, were tweaked, even slightly, it would have prevented the formation of the components necessary for life in the universe—including planets, stars, and galaxies. But recent studies, detailed in a new report by the Foundational Questions Institute, FQXi, propose that intelligent life could have evolved under drastically different physical conditions. The claim undermines a major argument in support of the existence of a multiverse of parallel universes.

“The tuning required for some of these physical parameters to give rise to life turns out to be less precise than the tuning needed to capture a station on your radio, according to new calculations,” says Miriam Frankel, who authored the FQXi report, which was produced with support from the John Templeton Foundation. “If true, the apparent fine tuning may be an illusion,” Frankel adds.

Over the last few decades, the subject of fine tuning has attracted some of the sharpest minds in physics. By probing the universe’s physical laws and precisely pinning down the values of physical constants—such as the masses of elementary particles and the strengths of forces—physicists have discovered that surprisingly small variations in these values would have rendered the universe lifeless. This led to a puzzle: why are physical conditions seemingly tailored towards human existence?