Modern chips: many steps, low energy consumption.

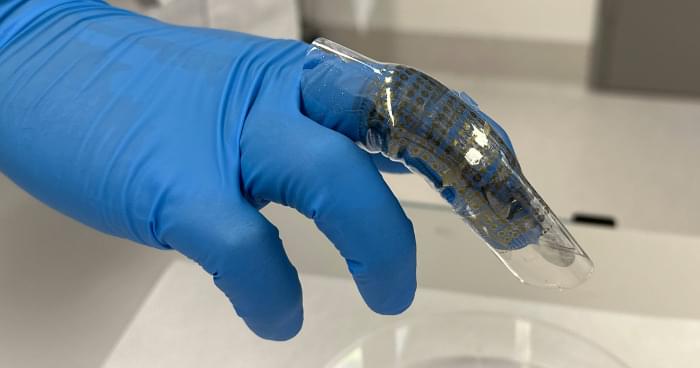

These key requirements for a chip are summed up mathematically by the parameter TOPS/W: “tera-operations per second per watt”. This can be seen as the currency for the chips of the future. The question is how many trillion operations (TOP) a processor can perform per second (S) when provided with one watt wordpress of power. The new AI chip, developed in a collaboration between Bosch and Fraunhofer IMPS and supported in the production process by the US company GlobalFoundries, can deliver 885 TOPS/W. This makes it twice as powerful as comparable AI chips, including a MRAM chip by Samsung. CMOS chips, which are now commonly used, operate in the range of 10–20 TOPS/W. This is demonstrated in results recently published in Nature.

In-memory computing works like the human brain.