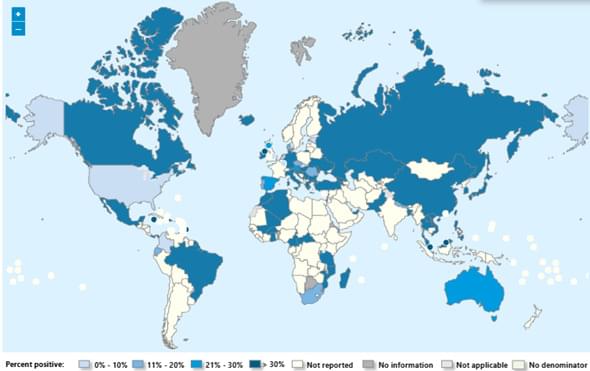

Seasonal influenza activity has increased globally in recent months, and influenza A(H3N2) viruses are predominant. This rise coincides with the onset of winter in the northern hemisphere. Epidemics and outbreaks of seasonal influenza and other circulating respiratory viruses can place significant pressure on healthcare systems. Although global activity remains within expected seasonal ranges, early increases and higher activity than typical at this time of year have been observed in some regions. Seasonal influenza could place significant pressure on healthcare systems even in non-temperate countries. Genetically drifted influenza A(H3N2) viruses, known as subclade K viruses, have been detected in many countries. While data on how well the vaccine works against clinical disease this season are still limited, vaccination is still expected to protect against severe illness and remains one of the most effective public health measures.

Surveillance

Due to the constantly evolving nature of influenza viruses, WHO continues to stress the importance of year-round global surveillance to detect and monitor virological, epidemiological and clinical changes associated with emerging or circulating influenza viruses that may affect human health and timely virus sharing for risk assessment. Countries are encouraged to remain vigilant to the threat of influenza viruses and review any unusual epidemiological patterns.