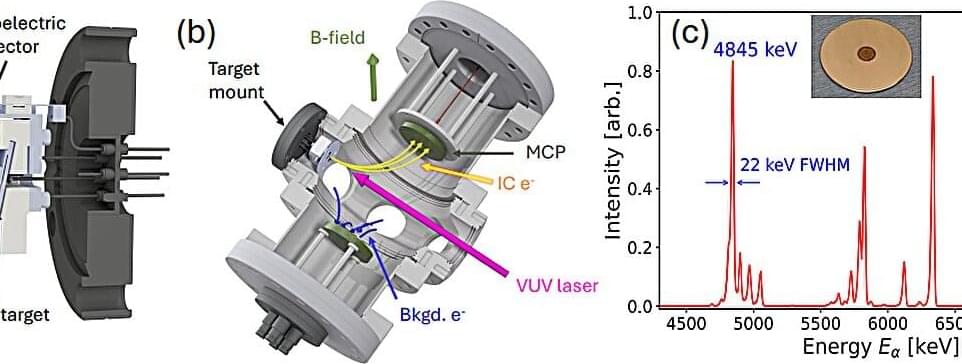

For 10 months, a SETI Institute-led team watched pulsar PSR J0332+5434 (also called B0329+54) to study how its radio signal “twinkles” as it passes through gas between the star and Earth. The team used the Allen Telescope Array (ATA) to take measurements between 900 and 1,956 MHz and observed slow, significant changes in the twinkling pattern (scintillation) over time.

The research is published in The Astrophysical Journal.

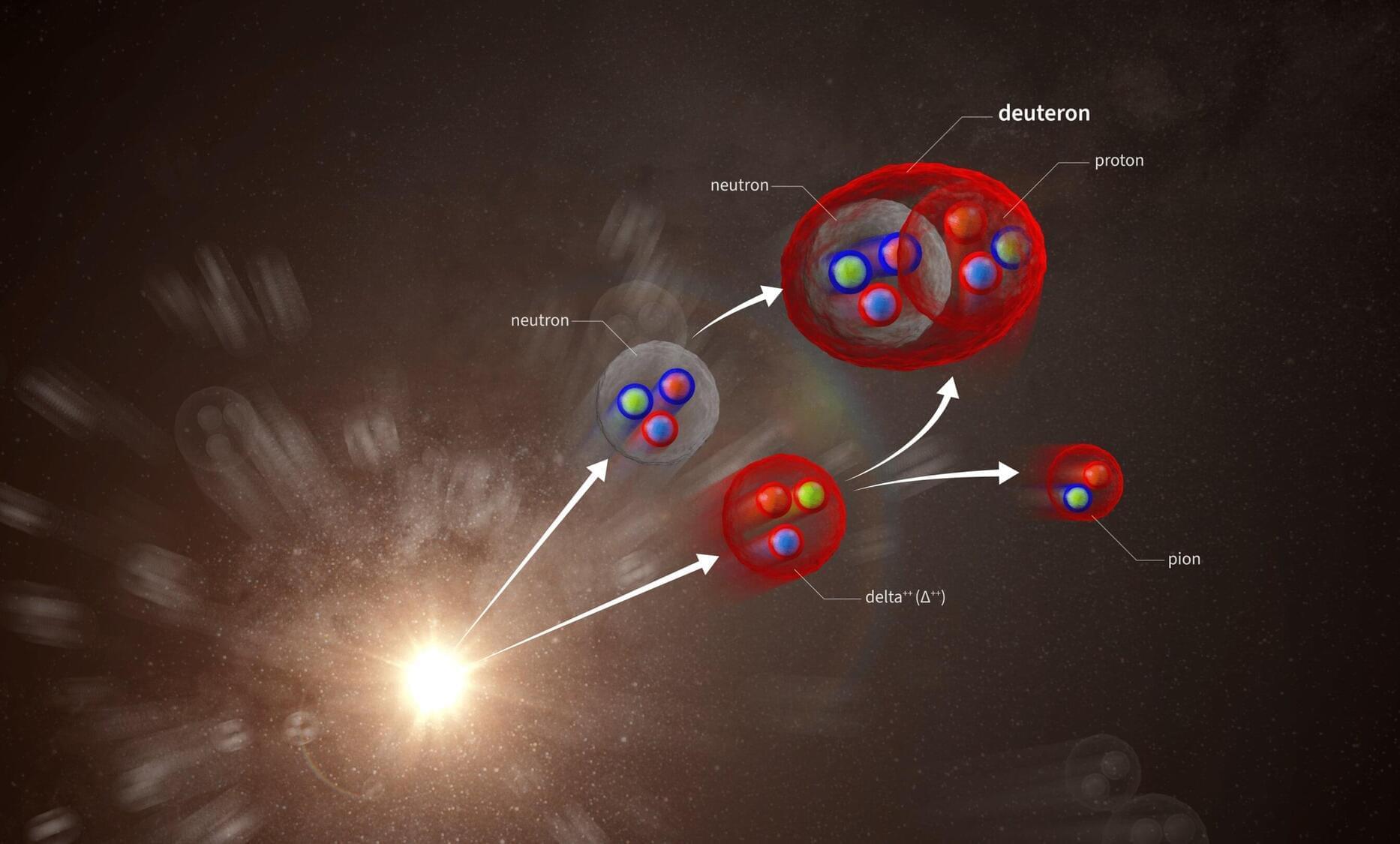

Pulsars are spinning remnants of massive stars that emit flashes of radio waves, a type of light, in very precise and regular rhythms, due to their high rotation speed and incredible density. Scientists can use sensitive radio telescopes to measure the exact times at which pulses arrive in the search for patterns that can indicate phenomena such as low-frequency gravitational waves.