Analysis of a large dataset from the Tokyo Stock Exchange validates a universal power law relating the price of a traded stock to the traded volume.

One often hears that economics is fundamentally different from physics because human behavior is unpredictable and the economic world is constantly changing, making genuine “laws” impossible to establish. In this view, markets are never in a stable state where immutable laws could take hold. I beg to differ. The motion of particles is also unpredictable, and many physical systems operate far from equilibrium. Yet, as Phil Anderson argued in a seminal paper [1], universal laws can still emerge at the macroscale from the aggregation of widely diverse microscopic behaviors. Examples include not only crowds in stadiums or cars on highways but also economic agents in markets.

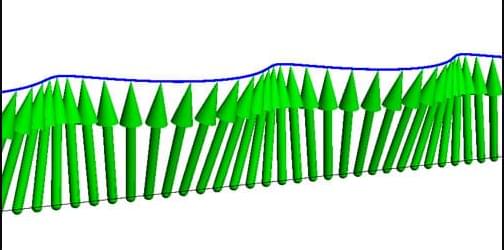

Now Yuki Sato and Kiyoshi Kanazawa of Kyoto University in Japan have provided compelling evidence that one such universal law governs financial markets. Using an unprecedentedly detailed dataset from the Tokyo Stock Exchange, they found that a single mathematical law describes how the price of every traded stock responds to trading volume [2] (Fig. 1). The result is a striking validation of physics-inspired approaches to social sciences, and it might have far-reaching implications for how we understand market dynamics.