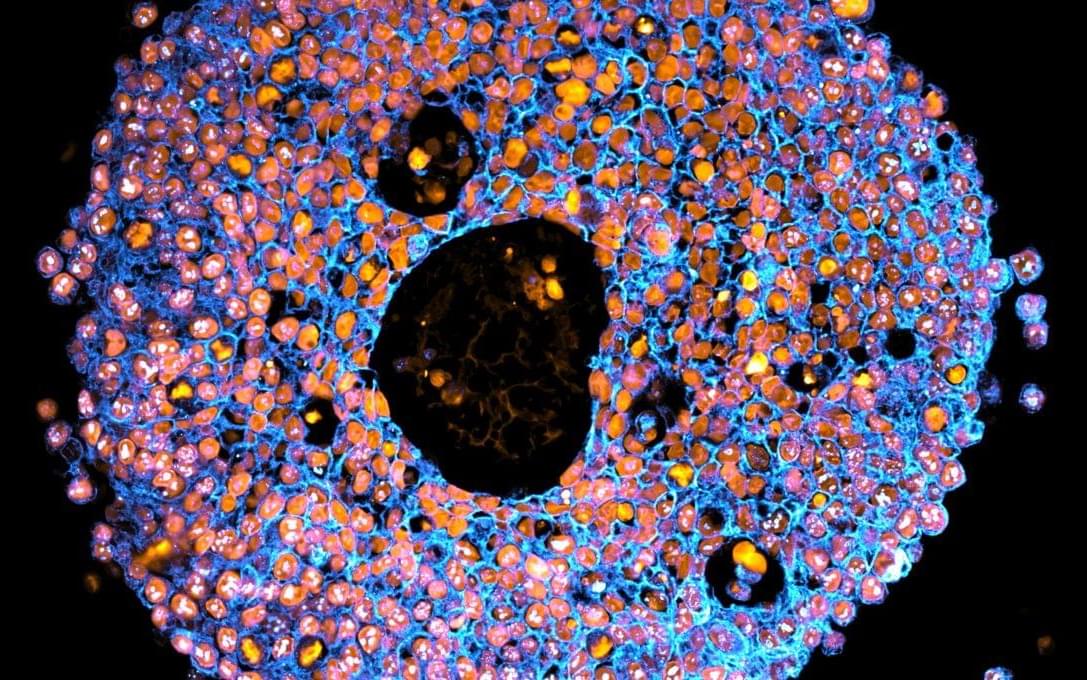

A person will have Alzheimer’s years before ever knowing it. The disorienting erasure of memories, language, thoughts—in essence, all that makes up one’s unique sense of self—is the final act of this enigmatic disease that spends decades disrupting vital processes and dismantling the brain’s delicate structure.

Once symptoms surface and doctors make a diagnosis, though, it can often be too late. Damage is widespread, impossible to reverse. No cure exists.

Attempts to develop drugs that clear away toxic accumulations of amyloid-beta and tau proteins—hallmarks of the disease that cause neurons to die—have ended in hundreds of failed clinical trials. Today, some scientists are skeptical over whether removing amyloid plaques is even enough. Others have a hunch that the best line of attack won’t target just one aspect of the disease, but many of them, all at once.