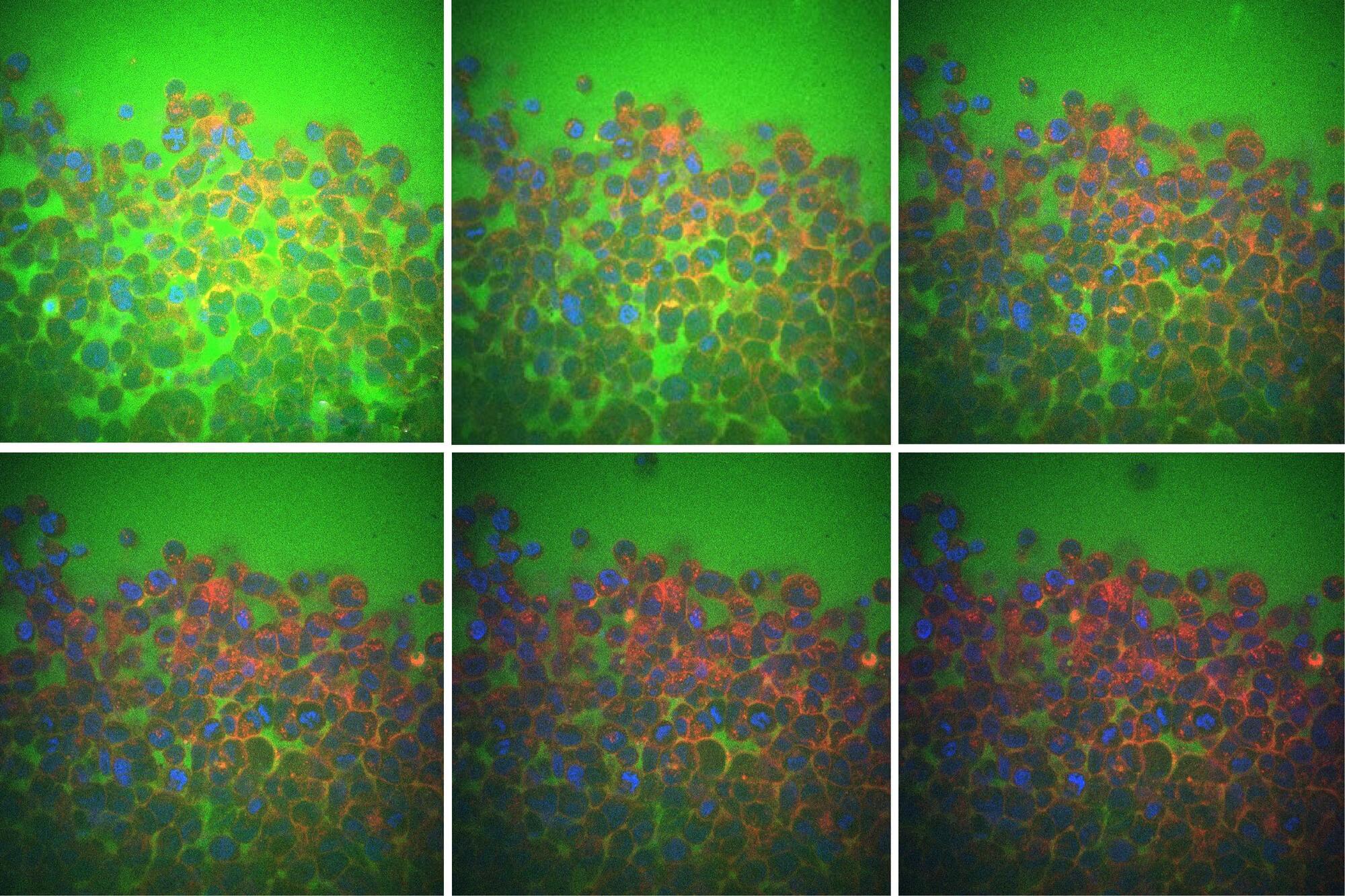

Water makes up around 60 percent of the human body. More than half of this water sloshes around inside the cells that make up organs and tissues. Much of the remaining water flows in the nooks and crannies between cells, much like seawater between grains of sand.

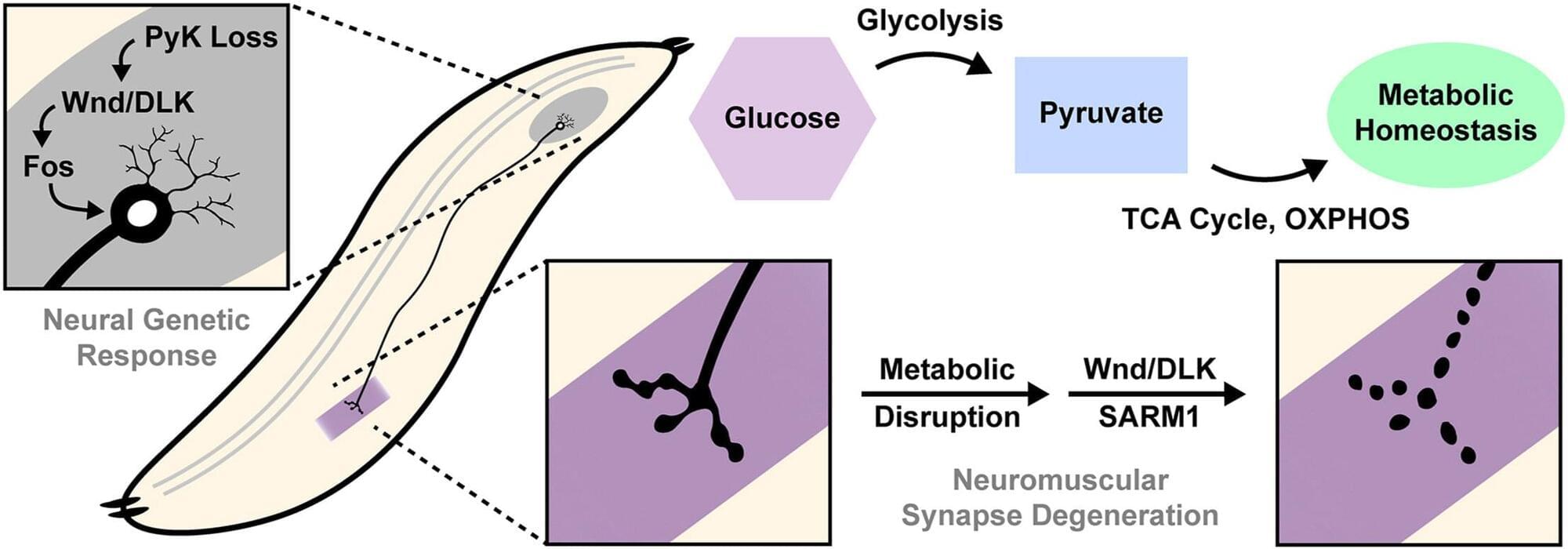

Now, MIT engineers have found that this “intercellular” fluid plays a major role in how tissues respond when squeezed, pressed, or physically deformed. Their findings could help scientists understand how cells, tissues, and organs physically adapt to conditions such as aging, cancer, diabetes, and certain neuromuscular diseases.

In a paper appearing today in Nature Physics, the researchers show that when a tissue is pressed or squeezed, it is more compliant and relaxes more quickly when the fluid between its cells flows easily. When the cells are packed together and there is less room for intercellular flow, the tissue as a whole is stiffer and resists being pressed or squeezed.