Learn about the Science of Intelligence through video lectures organized into series aimed at a general audience, the undergraduate level, and the research community.

Get the latest international news and world events from around the world.

Urgent Call to Protect Southern Ocean as Human Impact Grows

How can scientists protect biodiversity across the Earth while climate change continues to ravage the planet? This is what a recent study published in Conservation Biology hopes to address as an international team of researchers investigated how conservation efforts within the Southern Ocean should be addressed due to human activities (i.e., tourism, climate change, and fishing). This study holds the potential to help scientists, conservationists, and the public better understand the negative effects of human activities on the Earth’s biodiversity, specifically since the Southern Ocean is home to an abundance of species.

“Despite the planet being in the midst of a mass extinction, the Southern Ocean in Antarctica is one of the few places in the world that hasn’t had any known species go extinct,” said Sarah Becker, who is a PhD student in the Department of Environmental Studies at the University of Colorado Boulder (CU Boulder) and lead author of the study.

For the study, the researchers used the Key Biodiversity Area (KBA) standard—which used to identify sites of vital importance to preserving biodiversity—to examine species within the Southern Ocean. After analyzing tracking data for 13 Antarctic and sub-Antarctic seabirds and seals, the researchers found a total of 30 KBAs existed within the Southern Ocean, specifically sites used for migration, breeding, and foraging. This study improves upon previous research that identified KBAs on a macroscale, whereas this recent study focused on sites at the microscale. The researchers hope this study will help raise awareness for mitigating fishing activities in these areas along with developing improved conservation strategies, as well.

Robot planning tool accounts for human carelessness

A new algorithm may make robots safer by making them more aware of human inattentiveness. In computerized simulations of packaging and assembly lines where humans and robots work together, the algorithm developed to account for human carelessness improved safety by about a maximum of 80% and efficiency by about a maximum of 38% compared to existing methods.

The work is reported in IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics: Systems.

“There are a large number of accidents that are happening every day due to carelessness—most of them, unfortunately, from human errors,” said lead author Mehdi Hosseinzadeh, assistant professor in Washington State University’s School of Mechanical and Materials Engineering.

New technique prints metal oxide thin film circuits at room temperature

Researchers have demonstrated a technique for printing thin metal oxide films at room temperature, and have used the technique to create transparent, flexible circuits that are both robust and able to function at high temperatures.

The paper, “Ambient Printing of Native Oxides for Ultrathin Transparent Flexible Circuit Boards,” was published August 15 in the journal Science.

“Creating metal oxides that are useful for electronics has traditionally required making use of specialized equipment that is slow, expensive, and operates at high temperatures,” says Michael Dickey, co-corresponding author of a paper on the work and the Camille and Henry Dreyfus Professor of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering at North Carolina State University.

Engineers design tiny batteries for powering cell-sized robots

A tiny battery designed by MIT engineers could enable the deployment of cell-sized, autonomous robots for drug delivery within in the human body, as well as other applications such as locating leaks in gas pipelines.

The new battery, which is 0.1 millimeters long and 0.002 millimeters thick—roughly the thickness of a human hair—can capture oxygen from air and use it to oxidize zinc, creating a current of up to 1 volt. That is enough to power a small circuit, sensor, or actuator, the researchers showed.

“We think this is going to be very enabling for robotics,” says Michael Strano, the Carbon P. Dubbs Professor of Chemical Engineering at MIT and the senior author of the study. “We’re building robotic functions onto the battery and starting to put these components together into devices.”

Huge Lake on Mars // Fate of Milkdromeda // Hope for VIPER Rover

Vast amounts of water found on Mars, but there’s a catch, Milky Way and Andromeda might not merge after all, a planet found before it gets destroyed, and an easier way to terraform Mars.

👉 Submit Your Questions for Patreon Q\&A:

/ 110229335

🦄 Support us on Patreon:

/ universetoday.

📚 Suggest books in the book club:

/ universe-today-book-club.

00:00 Intro.

00:16 Water found on Mars.

02:55 Huge lake on Mars.

04:20 Terraforming Mars.

08:05 VIPER might be saved.

09:38 Milkdromeda might not be happening.

10:53 Vote results.

11:28 Planet on the verge of destruction.

13:09 New way of detecting supermassive black holes.

14:21 Vera Rubin’s secondary mirror.

15:40 More space news.

16:11 Livestreams and Q\&A

Host: Fraser Cain.

Breakthrough brain-computer interface allows man with ALS to speak again

“Not being able to communicate is so frustrating and demoralizing. It is like you are trapped,” Harrell said. “Something like this technology will help people back into life and society.”

For the researchers involved, seeing the impact of their work on Harrell’s life has been deeply rewarding. “It has been immensely rewarding to see Casey regain his ability to speak with his family and friends through this technology,” said the study’s lead author, Nicholas Card, a postdoctoral scholar in the UC Davis Department of Neurological Surgery.

Leigh Hochberg, a neurologist and neuroscientist involved in the BrainGate trial, praised Harrell and other participants for their contributions to this groundbreaking research. “Casey and our other BrainGate participants are truly extraordinary. They deserve tremendous credit for joining these early clinical trials,” Hochberg said. “They do this not because they’re hoping to gain any personal benefit, but to help us develop a system that will restore communication and mobility for other people with paralysis.”

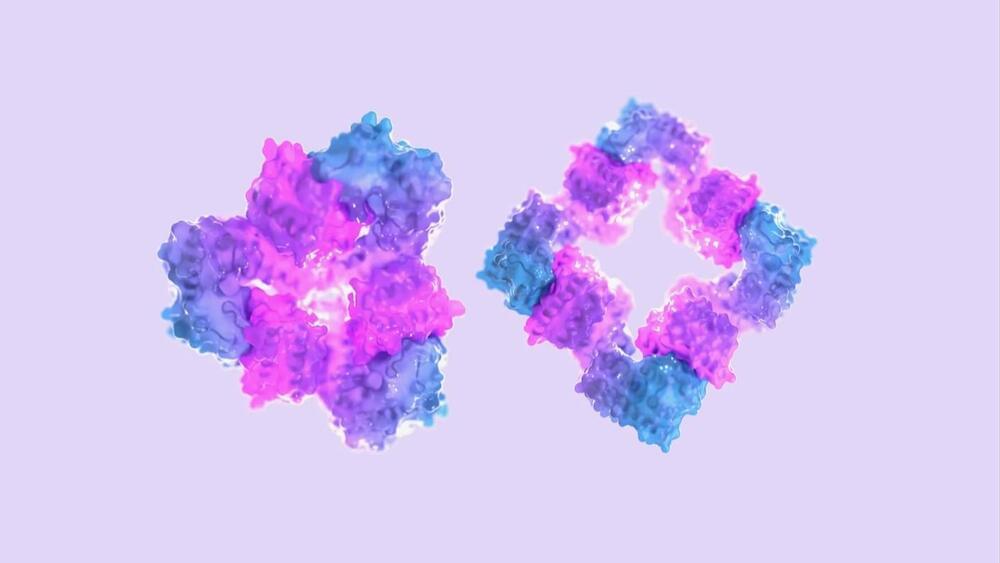

‘Startling Advance’ in Designer Proteins Opens a World of Possibility for Biotech

This type of molecular collaboration has inspired scientists for nearly a century. Here, oxygen is the effector. It flips a protein switch, helping proteins better carry oxygen through the body. In other words, it may be possible to optimize protein functions with an alternative effector drug.

The problem? The original inspiration is wonky. Sometimes hemoglobin proteins carry oxygen. Other times they don’t. In 1965, a French and American collaboration found out why. Each protein alternates between two three-dimensional shapes—one that carries oxygen and another that doesn’t. The shapes can’t coexist in the assembled protein to carry oxygen: It’s all-or-none, depending on the presence and amount of the effector.

The new study built on these lessons to guide their AI-designed proteins.

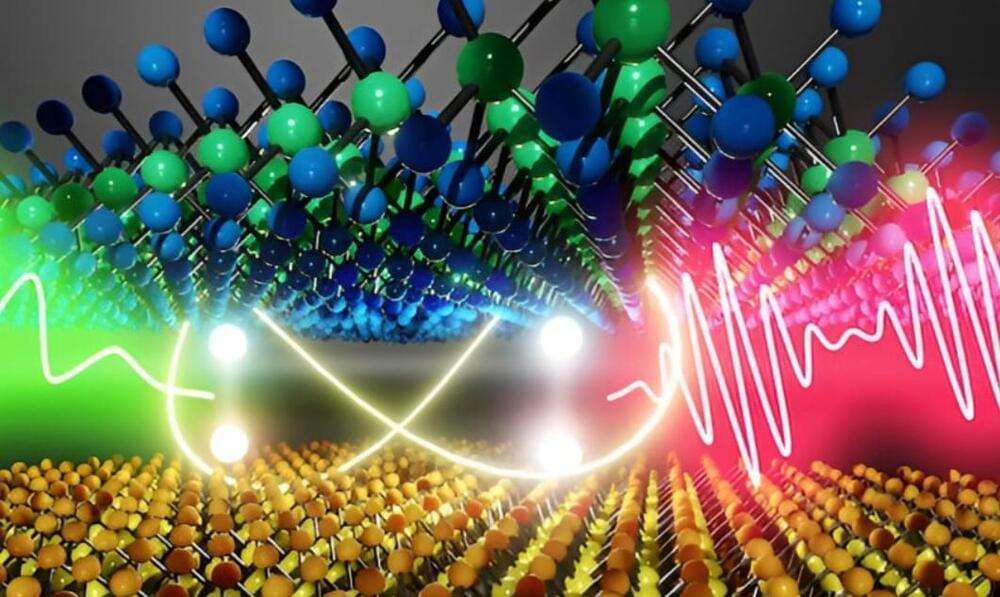

Nano-Semiconductors Poised to Disrupt Quantum Technology with Moiré Excitons as Qubits

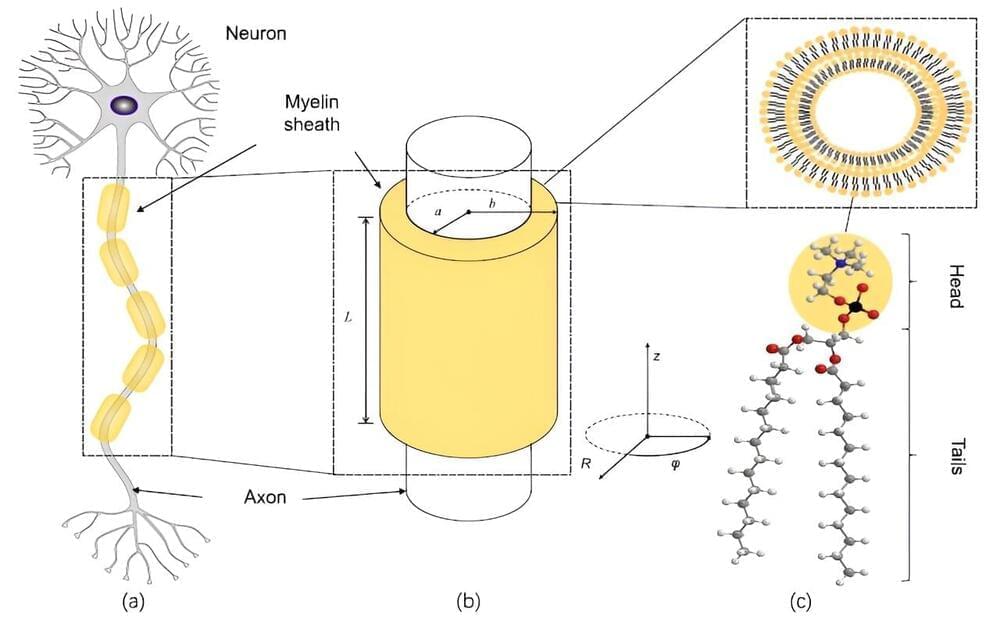

Quantum technology relies on qubits, the fundamental units of quantum computers, whose operation is influenced by quantum coherence time. Scientists believe that moiré excitons — electron-hole pairs trapped in overlapping moiré interference fringes — could serve as qubits in future nano-semiconductors. However, previous limitations in focusing light have caused optical interference, making it difficult to measure these excitons accurately.

Kyoto University researchers have developed a new technique to reduce moiré excitons, allowing for accurate measurement of quantum coherence time. Their findings, published in Nature Communications, reveal that the quantum coherence of a single moiré exciton remains stable for over 12 picoseconds at −269°C, significantly longer than that of excitons in traditional two-dimensional semiconductors. The confined moiré excitons in interference fringes help maintain quantum coherence, advancing the potential of quantum technology.

“We combined electron beam microfabrication techniques with reactive ion etching. By utilizing Michelson interferometry on the emission signal from a single moiré exciton, we could directly measure its quantum coherence time,” said Kazunari Matsuda of KyotoU’s Institute Advanced Energy.