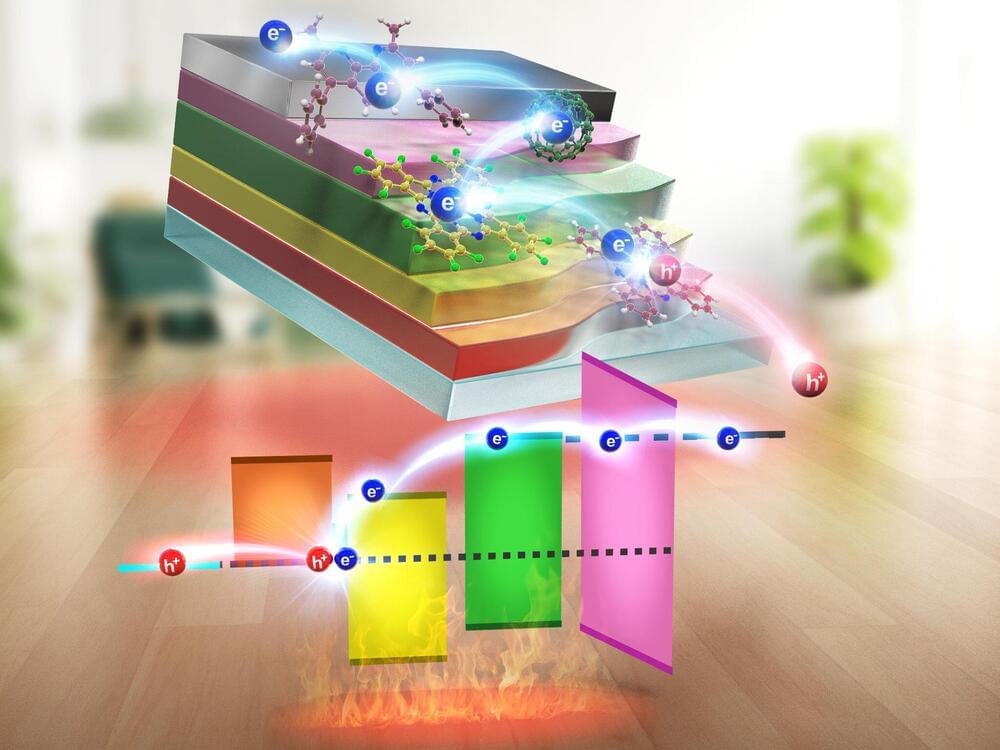

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a vital biological molecule that plays a significant role in the genetics of organisms and is essential to the origin and evolution of life. Structurally similar to DNA, RNA carries out various biological functions, largely determined by its spatial conformation, i.e. the way the molecule folds in on itself.

Now, a paper published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) describes for the first time how the process of RNA folding at low temperatures may open up a novel perspective on primordial biochemistry and the evolution of life on the planet.

The study is led by Professor Fèlix Ritort, from the Faculty of Physics and the Institute of Nanoscience and Nanotechnology (IN2UB) of the University of Barcelona, and is also signed by UB experts Paolo Rissone, Aurélien Severino, and Isabel Pastor.