📝 — Kono, et al.

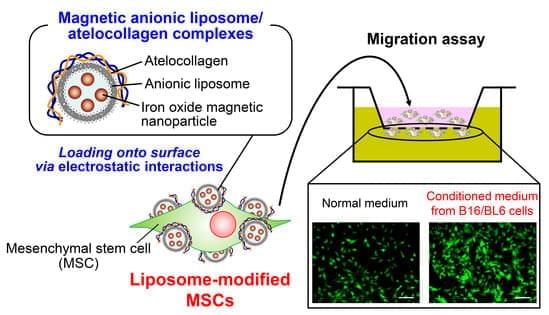

In this paper, the authors attempted to load liposomes on the surface of MSCs by using the magnetic anionic liposome/atelocollagen complexes that we previously developed and assessed the characters of liposome-loaded MSCs as drug carriers.

Full text is available 👇

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have a tumor-homing capacity; therefore, MSCs are a promising drug delivery carrier for cancer therapy. To maintain the viability and activity of MSCs, anti-cancer drugs are preferably loaded on the surface of MSCs, rather than directly introduced into MSCs. In this study, we attempted to load liposomes on the surface of MSCs by using the magnetic anionic liposome/atelocollagen complexes that we previously developed and assessed the characters of liposome-loaded MSCs as drug carriers. We observed that large-sized magnetic anionic liposome/atelocollagen complexes were abundantly associated with MSCs via electrostatic interactions under a magnetic field, and its cellular internalization was lower than that of the small-sized complexes.