Israel expects its “Iron Beam” laser defense system to be operational within one year, saying it will bring “a new era of warfare” as it engages in a war of drones and missiles with Iran and its regional partners.

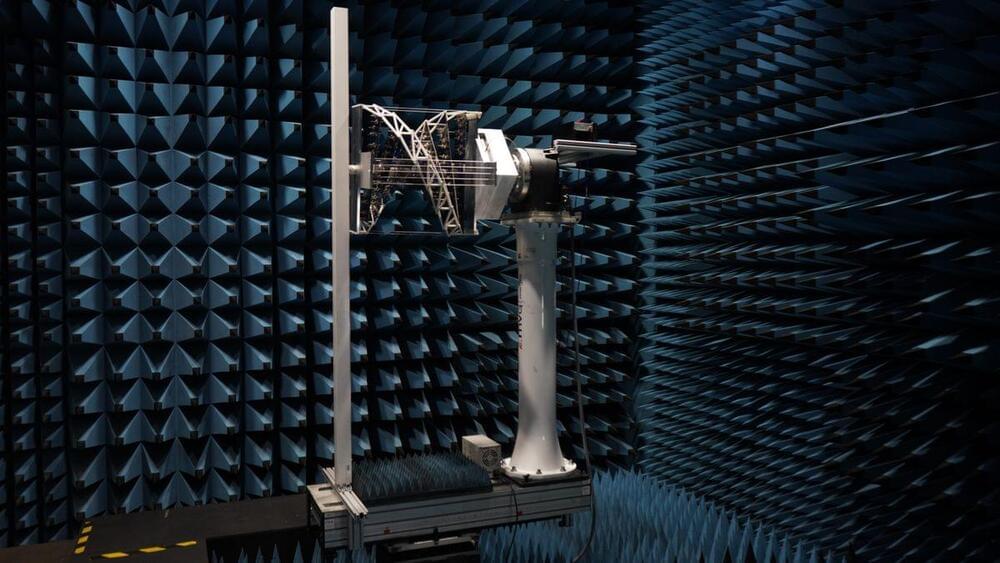

The Jewish state spent more than $500 million on deals this week with Israeli developers Rafael Advanced Defense Systems, architect of Israel’s Iron Dome, and Elbit Systems to expand production of the shield. Dubbed the Iron Beam, the shield aims to use high-power lasers to counter an array of projectiles, including missiles, drones, rockets and mortars, Israel’s defense ministry said this week.

“It heralds the beginning of a new era in warfare,” Eyal Zamir, director general of the defense ministry, said in a statement this week. “The initial capability of the ground-based laser system… is expected to enter operational service within one year,” he said.