Physicists from the University of the Witwatersrand (Wits) have developed an innovative computing system using laser beams and everyday display technology, marking a significant leap forward in the quest for more powerful quantum computing solutions.

The breakthrough, achieved by researchers at the university’s Structured Light Lab, offers a simpler and more cost-effective approach to advanced quantum computing by harnessing the unique properties of light. This development could potentially speed up complex calculations in fields such as logistics, finance and artificial intelligence. The research was published in the journal APL Photonics as the editor’s pick.

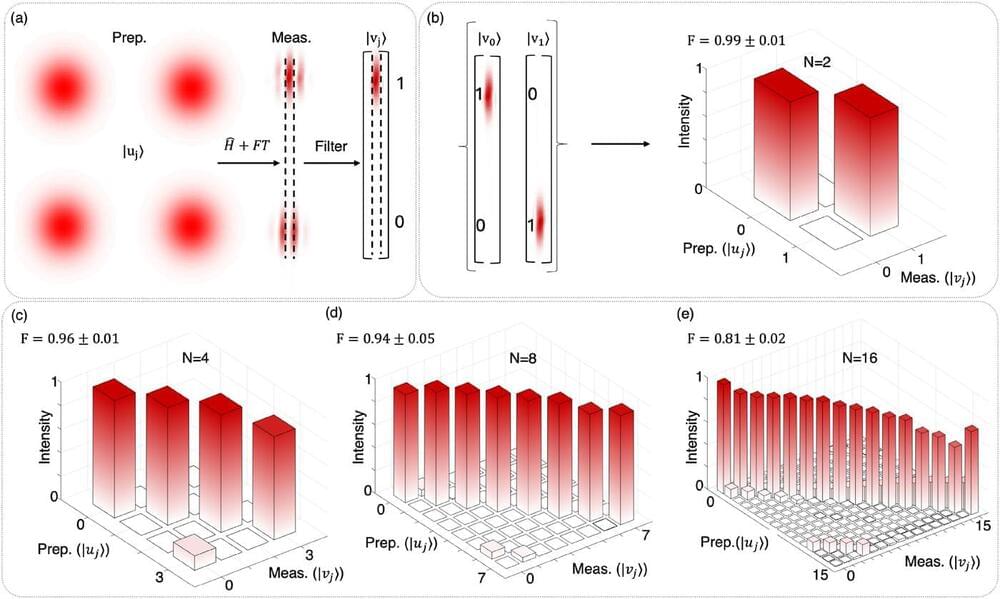

“Traditional computers work like switchboards, processing information as simple yes or no decisions. Our approach uses laser beams to process multiple possibilities simultaneously, dramatically increasing computing power,” says Dr. Isaac Nape, the Optica Emerging Leader Chair in Optics at Wits.